Reviews & Articles

Review of the Venice Biennale: 'The End of Art – Again (and its Beginning)'

Helen GRACE

at 5:10pm on 13th June 2024

Maria Madeira, Kiss and Don't Tell (2024) (detail). Exhibition view: Timor-Leste Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale, Foreigners Everywhere (20 April–24 November 2024). © Maria Madeira. Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne. Photo: Cristiano Corte.

All photos by Helen Grace, unless otherwise noted

'The End of Art – Again (and its Beginning)'

by Helen Grace

01: Venice, April 2024

Each afternoon during the 2024 Venice Biennale vernissage, fierce storm clouds gathered over the city, threatening awe-filled tempest and a deluge, but each time, a little rain fell and the weather cleared. Endless storms have gathered around the Biennale, in its 130-year history and yet they have dissipated and it persists as a major global event in the artworld, in spite of being declared obsolete. If a function does remain for the national model on which it’s built, perhaps it simply provides the scaffold for a different construction altogether. This year, that construction is arguably the curated theme: Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere, chosen by its Brazilian curator, Adriano Pedrosa, the first curator from the Global South. Meanwhile, the Antipodes – or Oceania in general – ran away with the top prize Golden Lions for Best National Participation (Australia’s Archie Moore) and New Zealand/Aotearoa’s Mataaho Collective, (Best Artist in the International Exhibition).

So, what’s going on here and how to make sense of it? To answer these questions, I want to move away from calling the Venice Biennale an event – in any case, in three days, it’s impossible to get any sense of a singular event. Rather, I want to call it a situation, in the sense in which Lauren Berlant understands it:

“A situation is a state of things in which something that will perhaps matter is unfolding amid the usual activity of life. it is a state of animated and animating suspension that forces itself on consciousness, that produces a sense of the emergence of something in the present that may become an event. “ (emphasis in original)[1]

In the situation of the Biennale, you can move around the edges of the 60th edition and in a more marginal way, you can bring the overall phenomenon into sharper focus. The first irony that you encounter is that the city of Venice is still holding onto its medieval status as a city-state by having its own pavilion within the Giardini, but the state of Italy does not (its national pavilion is in the Arsenale, beside China’s – though there are rumours that the Biennale’s new right-wing President, Pietrangelo Buttafuoco may consider restoring the main exhibition building of the Giardini back to its use as the Italian national pavilion, which it was, from 1932 when the Fascists were in power).

Starting with the Giardini, an open history book of a passing world that still holds onto its power, (funded now by the rest of the world), one-third of the national pavilions are here, established in the three distinct periods of Giardini development: the pre-First World War period, when the European empires still existed[2]; the pre-Second World War period, when Mussolini ruled[3] and the post-war period[4]. With the exception of Egypt and the US, no permanent pavilion of any nation outside of Europe existed in the Giardini until after the Second World War.

Since then, this predominantly European affair has increasingly found itself beset by strangers, acknowledged most explicitly in this year’s 60th Biennale theme: Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere.

Israel’s pavilion opened in 1952. There is no Palestine pavilion because the Italian Government doesn’t recognize the state, but this year a pro-Palestinian group, Art Not Genocide Alliance (ANGA) protested in front of the US and Israel pavilions on the first day of the Vernissage. This followed the unprecedented move by the curators of the Israeli pavilion to close it until “a ceasefire and hostage release agreement is reached."

In 1984, there were only 33 national pavilions in the overall Biennale – but in 2024, there are 87 – an exponential growth rate in global art that sees a point in coming to Venice. The sense of dynamism and energy of the Biennale is shifting too – away from the named, permanent pavilions, stolidly in place, to the unnamed, and more or less temporary pavilions, established in and around the Arsenale and elsewhere all over Venice, where a fresher feeling circulates.

Even so, only twice in the last 40 years has the Best National Participation Golden Lion gone to a country outside of Europe or North America: Angola in 2013 and, this year for the first time, Australia. Perhaps it's a slow, alphabetical thing – in which case it will be several centuries before Zimbabwe gets a shot at it.

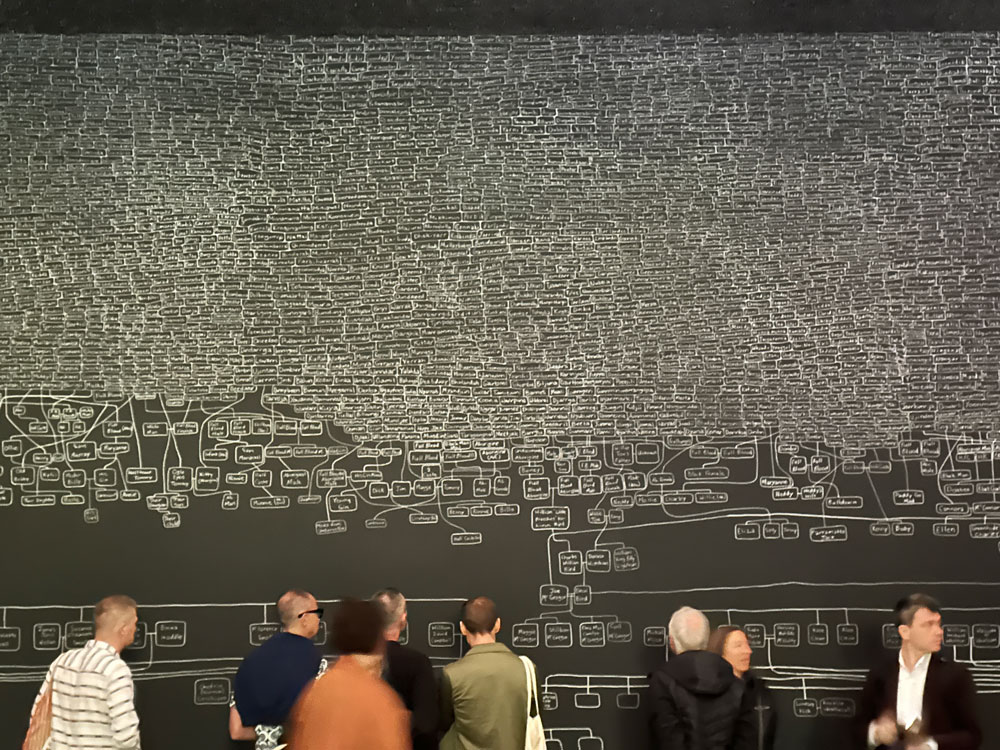

02: Archie Moore, kith and kin (Photo: Helen Grace)

Archie Moore’s kith and kin (curated by Ellie Buttrose) is a superlative installation in the Australian pavilion, minimal even in the necessary excess of detail it presents. Its success lies in the formal restraint it achieves: a brilliant idea, perfectly executed within the specific architecture of the space it occupies. So many of the pavilions are filled to the brim with stories as strong as Moore’s, and physical contents that overstate the case. Here, however, it is the conceptual control and the perfect choice of materials that allows the artist to bring to Venice – a city of demonstrable generations upon generations – this entirely generative work of the generations, possessing immense historical force and contemporary invention.

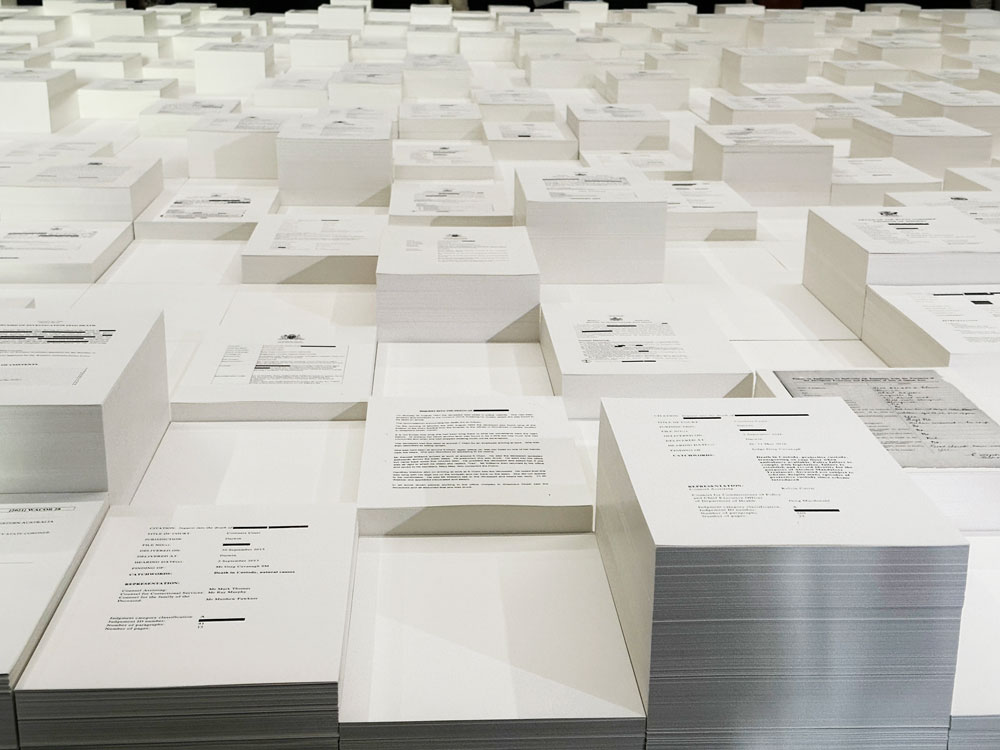

03: Archie Moore, kith and kin (Photo: Helen Grace)

The arrangement of endless documents of coronial inquests as a central sculptural installation condenses the traumatic force of this history, yet it floats on water. The sheer weight of timeless generations, rendered as chalk drawings somehow resurrects the dead, contained in bureaucratic reports, re-animating them as planetary system.

04: Mataaho Collective, Takapau (Photo: Helen Grace)

The large scale Takapau installation by Mataaho Collective (a collaboration by four Māori women) completes the Antipodean rout of Venice this year. A work of the simplest materials used to create monumental impact, Takapau is based on whariki takapau – finely woven floormats, used on special occasions, such as births, weddings and tangihanga (funeral rites), to add mana or spiritual life force and healing power. This woven universe is one of the first works you pass under as you enter the main Arsenale exhibition and the installation effectively plays with the flow of light from exterior to interior space, illuminating the detailed complexity of the weave, which we see from below, rather than from above.

Astutely positioned close to the entrance of the show, this masterwork is made from materials as basic as hi-vis polyester tie-downs, stainless steel buckles and J-hooks, transformed in the process of bringing a sense of ceremony to the overall exhibition, imbuing it – and the world – with the gift of mana: a work that visualises collective labour, materialising it as forcefully as possible. The achievement is all the more salutary because New Zealand/ Aotearoa chose not to represent itself at Venice this year for national budgetary reasons – and evidently this wasn’t a bad decision.

05: Maria Madeira, Kiss and Don't Tell (2024) (detail). Exhibition view: Timor-Leste Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale, Foreigners Everywhere (20 April–24 November 2024). © Maria Madeira. Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne. Photo: Cristiano Corte.

Although old European nations dominate the Giardini, the art of new nations invigorates, in temporary pavilions all over the city – and the newest this year is Timor-Leste, with a delicate installation by Maria Madeira, (curated by Natalie King) on the ground floor of Palazzo Ravà, San Polo 1100. Twenty-five years after the nation first voted for its independence (and was brutally punished for it by Indonesia), the country’s Prime Minister, Xanana Gusmão quietly steps from a traghetto just beside Spazio Ravà to open the country’s first national pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

If this were the pavilion of France, Germany or the US, a huge media scrum would surround the event and the security detail would be extensive. But instead we have this quite extraordinary occurrence in which ‘the father of our nation’ (as he is described in the catalogue by Jorge Soares Cristavão, the exhibition’s commissioner) discreetly opens an exhibition. This crucial performative part of an emergent phenomenon is precisely one of those ‘situations’ Berlant has in mind: ‘a state of animated and animating suspension that forces itself on consciousness’. Maria Madeira’s installation, Kiss and Don’t Tell – another body of work using very basic materials – re-enacts some of the historical trauma and brutality of the formation of this de-colonized nation.

06: Maria Madeira, Kiss and Don't Tell (2024) (detail). Exhibition view: Timor-Leste Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale, Foreigners Everywhere (20 April–24 November 2024). © Maria Madeira. Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne. Photo: Cristiano Corte.

The main panelled paintings/collage in pigment, betel nut, tais, lipstick and earth opens out the work, but its potency is enhanced in a very intelligently-installed video documentation of a performance at the heart of the work, placed in a narrow side-room, affectively pressing the audience against the screen. And Maria Madeira enters the world stage.

Marcel Proust pictures Venice as a hub of diplomatic intrigue, in his famous account written at the beginning of the First World War [5] – right at the point that the Biennale is establishing its place in the world. Today, the global stage is much larger than the confined, insular world of In Search of Lost Time’s Venetian hotel dining room gossip, but Venice is still a location of delicate behind-the-scenes negotiation. For example, a subtle politics of hierarchy and precedence played out in the opening of the Hong Kong pavilion – which had to wait until after China’s national pavilion, in the Arsenale, had officially opened.

Hong Kong occupies a position similar to that of Venice itself in the Biennale in having a pavilion separate from the nation’s official pavilion – and neither are listed as national participations in the Art Guide. Taiwan is in a similar complicated position, resolved by cultural/diplomatic subtlety: both Hong Kong and Taiwan are listed as ‘Official Collateral Events’, granting them a distance, a kind of diplomatic immunity, while the geographic origin of both pavilions is displaced by the title of the respective exhibitions within them.

Perfectly positioned on Campo della Tanna, opposite the main Arsenale entrance, Hong Kong's Trevor Yeung’s fishless aquariums in his installation, Courtyard of Attachments (curated by Olivia Chow) allude to a fragile social ecology, in which everything is visible but hidden; water from the Grand Canal is drawn into the filtration system and fed back into the lagoon, in endless renewal: a two-way process of intricate dialogue and exchange.

07: Opening Ceremony of Trevor Yeung: Courtyard of Attachments, Hong Kong in Venice. Photo: Winnie Yeung @ Visual Voices. Courtesy of M+, Hong Kong

M+, the relatively new – and extraordinarily popular – contemporary art museum is a key sponsor of the pavilion, along with the official Hong Kong Arts Development Council. Official comments in speeches at the opening thank ‘our country’ for what it enables – audible adaptation to changing circumstances, seeming to echo Proust’s image of Venice as hub of hidden and behind-the-scenes parleying of possibilities at a distance from the nation itself.

08: Still from Yuan Goang-Ming, Everyday Maneuver (2018) 5.57” single-channel video. Courtesy: the artist

The Taiwan pavilion, in Palazzo delle Prigioni (the former ‘Prigioni Nuove’ or ‘New Prison’) features pioneering media artist, Yuan Guong-Ming’s exhibition, Everyday War (curated by Abby Chen), an installation of video works, drawing and performance made since 2014. Taipei Fine Arts Museum is the official sponsor and the central work in this carefully composed suite loops between Everyday Maneuver (2018) – aerial footage of the deserted streets of Taipei during the annual Wanan Air Raid Drill, when, for half an hour in the middle of the day, life comes to a standstill – and The 561st Hour of occupation (2014) – the chamber of Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan, during the 2014 Sunflower Movement.

09: Still from Yuan Goang-Ming, The 561st Hour of Occupation, (2014) 5.56” single-channel video. Courtesy: the artist

The work is well located in the 17thC Prigioni Nuove. Once it housed the Judiciary overseeing common criminals and prisoners’ surveillance but in 1871, King Vittorio Emanuele II set up "the Work of Relief for poor and needy artists”, royal patronage eventually handing this work – and this site – to the Circolo Artistico di Venezia, in 1922 – the day after the opening of the XIII Biennale. The Circulo still retains control of this former prison/charity location for needy artists – and, no doubt, surveillance continues.

10: Chitti Kasemkitvatana and Nakrob Moonmanas, Our Place in Their World, 2023. Two-channel video installation, color, sound, 4:00 min. Installation view. Commissioned by Bangkok Art Biennale Foundation. Collection of the Artists. Courtesy the Artists; Bangkok Art Biennale. © Chitti Kasemkitvatana and Nakrob Moonmanas

The Thailand pavilion – another official Collateral Event charts a different kind of distance for itself. Housed in the sumptuously restored Palazzo Smith Mangilli Valmarana (former residence of the 18thC British Consul, Joseph Smith – Canaletto’s dealer), Bangkok Art Biennale inserts itself into Venice, appropriating it in The Spirits of Maritime Crossing, an impressive group show, curated by Biennale director, Apinan Poshyananda, arguably the most astute of cultural diplomats in South East Asia.

It turns out that the modernising King Chulalongkorn – Rama V – was the first Asian monarch to visit the Venice Biennale, which he did in 1897 and 1907 and his son, King Vajiravudh – Rama VI – was so impressed by Venice that he translated Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice into Thai, built the neo-Venetian Gothic Palace Villa Norasingh (now the Thai House of Parliament) and influenced the course of modern Thai art by bringing the Italian artist, Corrado Feroci to Thailand, in 1923.

The artists Chitti Kasemkitvatana and Nakrob Moonmanas install a two-channel video work, Our Place in Their World, revising stories of Siamese travelers in Europe, surrounded by Neo-classical Graeco-Roman figures as elaborately framed murals. In another room, Marina Abramović and Thai Classical Mask dance (Kohn) artist, Pichet Klunchen’s collaborative video projection achieves an uncanny effect in the relocation of the costumed dancer in Venice – although Abramović’s sombre intonation has the sense of another lost European seeking redemption in the East.

11: Bouchra Khalili, Mapping Journey Project (2008-11)

Adriano Pedrosa’s curated show, the monumental Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere, fills the Arsenale and the Central Pavilion of the Giardini with the work of over 300 artists. Dazzling in its coherence, (though not everyone’s opinion), the show requires more than this brief summary. Highlights in the Arsenale include a selection of works reproducing Lina Bo Bardi’s 1950s redesign of museum display in MASP (the São Paulo Museum of Art – where Pedrosa is currently artistic director), Moroccan/French artist, Bouchra Khalili’s remarkable Mapping Journey Project (2008-11) in which she poignantly charts the passage to and within Europe of a group of illegal immigrants, and Disobedience Archive – Marco Scotini’s video collection of artistic practices and political action (‘an archive of imaginaries’), presented in the form of a Zoetrope. London-based Italian artist Alessandra Ferrini’s Gaddafi in Rome (2022), in the Giardini Central Pavilion, looks at Italy’s north African colonialism, in a photograph of a meeting between Gaddafi and Berlusconi in 2009 – the very week that Italian Prime Minister was signing accords with the Tunisian president Kais Saied, providing business credit and investment to enable Tunisia to stop illegal migration from reaching Europe. History repeats …

Off-site, at S.a.L.E. Docks, I managed to catch a stunning conversation between the Yogyakarta-based activist collective, Taring Padi and Charles Esche, director of Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, revisiting the huge controversy that had taken place at documenta XV in 2022. There, Taring Padi were accused of anti-semitism because of an anti-militarist banner work they had made, criticising the repressions of 1965-66 in Indonesia, in which many of their friends and family had been killed. The documenta project is still mired in the aftermath of that controversy. This discussion effectively reframed the event, and though unconnected with the Biennale, illuminated its overall theme, Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere, and the complexities of hospitality and of how guests are permitted to behave in a culture that only has the concept of the guest worker. Currently, a Taring Padi exhibition is showing at Griffith University Art Museum in Brisbane.

Berlant’s sense of a situation – ‘a state of things in which something that will perhaps matter is unfolding…’ certainly applies. The 60th Venice Biennale is filled with emergent phenomena: first Global South curator; first Golden Lion for Australia and first for New Zealand/Aotearoa; first pavilions for Benin, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Timor Leste. Jaded responses will declare again that art is done – or overdone. But its beginnings are also visible around the edges, where new worlds – and imaginaries – form, in spite of the European civilizational project which increasingly excludes those outside its borders.

©Helen Grace, June, 2024

[1] Berlant, Lauren. Cruel Optimism, Duke University Press, 2011, p5

[2] so, Belgium, Hungary, Germany, Great Britain, France, Netherlands, Russia

[3] Spain, Czechoslovakia, United States, Denmark, Poland, Egypt, Serbia, Greece, Austria build pavilions

[4] Switzerland, Israel, Japan, Finland, Venezuela, Canada, Nordic Countries, Brazil. Uruguay, Australia, Korea – though Switzerland has participated since 1920

[5] Proust, The Fugitive, Ch 3, ‘Sojourn in Venice’ (Vol 5 of In Search of Lost Time), Yale University Press, 2023