Reviews & Articles

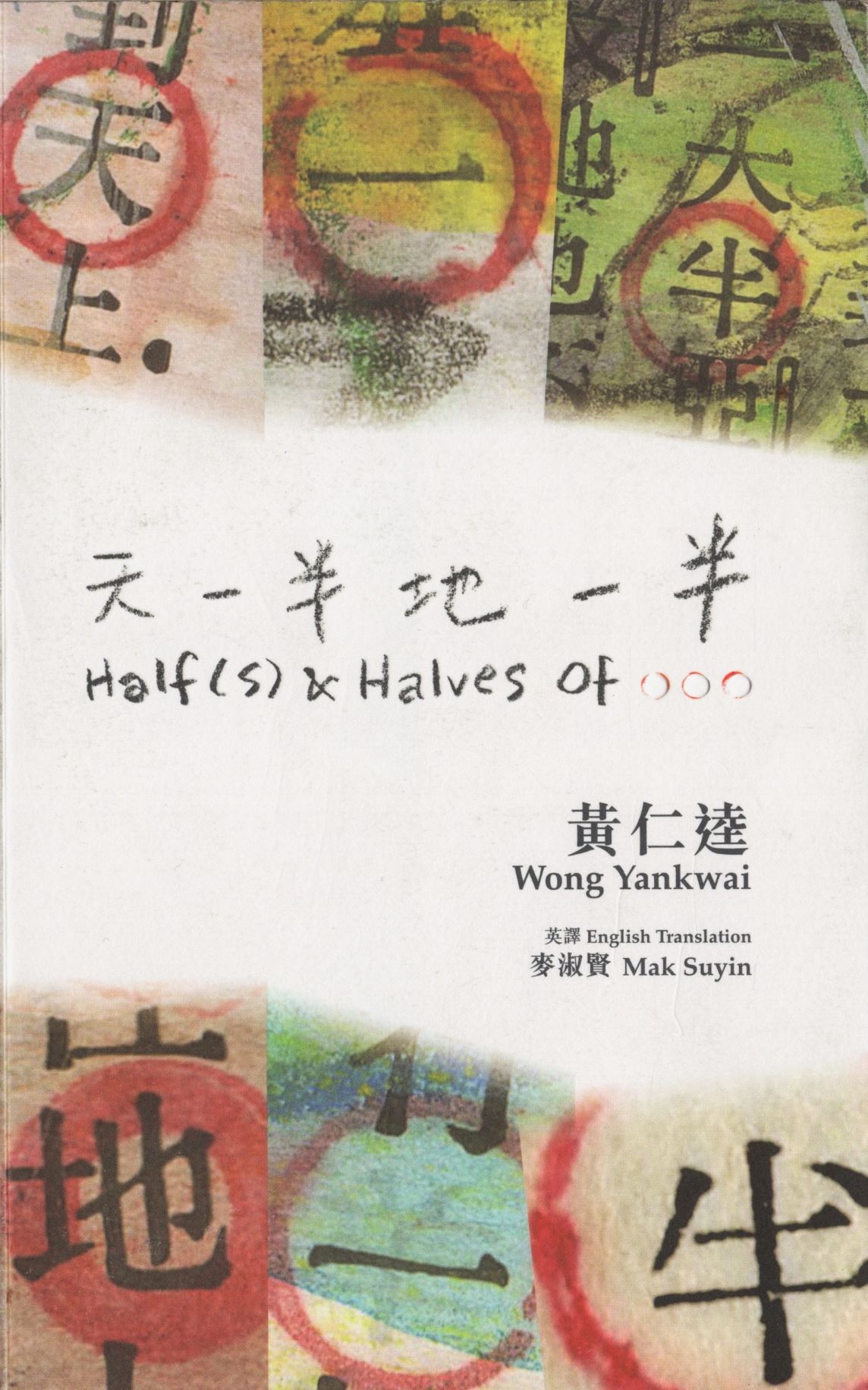

黃仁逵:《天一半地一半》 Wong Yankwai: Half(s) & Halves of...

John BATTEN

at 2:29pm on 17th April 2024

(A book review originally published in Artomity (Spring 2024) by John Batten in English and Chinese of Wong Yankwai's Half(s) & Halves of..., published in 2023 by Mount Zero Books)

Scroll down for English

書評:

撰文:約翰百德

黃仁逵:《天一半地一半》

英譯:麥淑賢(中英雙語,261頁)

2023年,見山書店出版

2023年年底,配合黃仁逵於香港兆基創意書院舉辦畫展,本書同時出版。書中25個短篇故事略有關聯,既是回憶錄也又是簡單的觀察。而最重要的,是書中充滿了反思:黃氏思考的時候,一般都是在手中拿著香煙站在街角,又或是來回街市買煙或買菜,他以諷刺手法寫下街景變化的所見所聞,也記下與其他街坊的對話。

每篇故事都配上兩張橫向和垂直上下並排的照片,同類編排也常見於黃氏的個人Facebook專頁。這些照片不完全是雙聯畫,也不完全順序。但它們是互相配對的,有時甚至完美得與鏡像一樣,默默地呈現些微差別,但兩張照片通常都在俏皮地你一言我一語。例如,在第 67 頁,兩個場景都是直望著街市,一條攤檔林立的街道:第一張照片捕捉了一名望著鏡頭的男子,他歪斜地靠左站著;下方第二張照片拍下了一隻黑白貓,頭正轉向右方。這種一張望左、一張望右的並置充滿趣味,黃氏的攝影作品再次證明了他作為攝影師/藝術家的獨到審美眼光。

黃氏是畫家、音樂家、攝影師、作家、設計師,有時還擔任電影美術指導。創作是他的日常,有時候在工作室,有時候與朋友在酒吧玩音樂。儘管黃氏不是藝術市場的熱賣藝術家,但M+選展寥寥無幾的香港藝術家之中,黃氏正是其中一位,而且也當之無愧;或許是因為黃氏作品觸及多種藝術,正好符合M+的「跨領域視覺文化收藏」宗旨。

本書的語氣平靜低調,譯者麥淑賢的英譯也捕捉了這種美妙的神韻。文字反映了黃仁逵的日常生活、想法和觀點,還有漫不經心地接受簡單生活的美好:「不抽煙的時候我也蹓躂,方圓一箭之遙,看這看那,每回都有得著,真沒有的話就回家,繼續我先前的行當。」

黃仁逵的照片和文字,清晰呈現出香港城市街頭生活裡的荒謬和巧合,每每令人會心微笑。可幸本書沒有賣弄懷舊,而是以當下為重心。雖然黃氏未有為過去感懷哀嘆,但顯然喜歡香港人堅毅不屈、近乎千載不變的特徵,還有他們經常不拘小節、腳踏實地的生活和價值觀;這些價值觀看起來或有點老氣,但仍然是香港人的普遍特徵,連年輕一代的身上都可以找到。

黃氏喜歡偶遇,喜歡短暫的共享時光——我可以想像,在相遇後能夠毫無包袱繼續生活。他憶述:「早兩夜風大雨大,我在一家茶餐廳外頭問人借火,那老人把一朵火苗護得,滴水不進,煙點好了,加一句:『易過借火。』那才是人話,三唔識七,自有三唔識七的對白。」

黃仁逵說著自己的年輕時代,故事之間互相交織,點到即止但令人印像深刻。其中一段軼事說到向魚販買魚,黃氏說:「他就是個搞裝置搞雕塑的」,因為他「把魚一尾一尾拼圖似的排好」。黃氏買了一條黃魚,回到家中,「......最後自然是讓我收拾了,並且把魚裡藏著的兩顆石子洗淨了,投到一個玻璃瓶裡,什麼時候,待瓶子裡的魚石分量足了,就可以封起來作個沙槌什麼的,送給愛音樂的小孩玩玩,我小時候有過這樣的玩具,那時候吃黃魚不用走多少路,每天玩一身大汗,回家就有了。」

雖然書中鮮有明確提及黃仁逵的藝術家生活,但整本書卻可以當作藝術家的生活來細閱。最後一篇是〈兩面牆的兩面〉,故事發生在黃氏經常玩音樂的Club 71酒吧,由書中稱為「G」的朋友經營。在酒吧結業前,黃仁逵打算把後、側兩面牆上的壁畫刷白,但白漆「水淋淋」,那畫又一點點地回來了。有些酒吧顧客見狀後試圖擦去白漆。有人問:「你看這些人是在破壞那畫還是不讓你破壞那畫?」黃氏回答說:「都不是。他們正在懷念一樣還沒有消失的東西。」

Book review:

by John Batten

Wong Yankwai: Half(s) & Halves of...

Translated by Mak Suyin (in English & Chinese, 261pp)

Published by Mount Zero Books, 2023

Published to coincide with a comprehensive exhibition of his paintings at HKICC Lee Shau Kee School of Creativity in late 2023, Wong Yankwai’s book of 25 loosely connected short stories is part memoir and part simple observation. Uppermost, it is contemplative: the writer musing, often cigarette in hand on a street corner, or on his walks to and then back from buying a packet of cigarettes or food at the market, featuring his wry surveillance of the changing streetscape and conversations with fellow street-habitués.

Each story is complemented by two accompanying landscape-format photographs placed vertically underneath each other, a format that is also regularly seen on his personal Facebook page. They are not quite a diptych and not quite a sequence. But they are matched, sometimes perfectly, like a mirror image, often quietly dissimilarly – but usually the two photographs bounce together with a similar playfulness. For example, on page 67, two scenes look directly along a street lined with market stalls: in the first photograph, a man is caught looking directly back towards the camera but standing askew towards the left; in the lower, second photograph, a black and white cat sits with its head turned to the right. It’s a lovely juxtaposition – heads left and right – and his photographs reinforce the view that the photographer/artist has a great aesthetic eye.

Wong is a painter, musician, photographer, writer, designer and sometime art director for films. He is constantly doing something creative, in his studio working or playing music in a bar with friends. Despite not being on the art market radar, he is one of a handful of Hong Kong artists that M+ prominently, and deservedly, features in its collection, possibly because his work covers a range of arts, fitting into the museum’s “interdisciplinary collection of visual culture”.

The book has a wonderfully nonchalant, understated tone, well captured in English by translator Mak Su-yin, with the writing reflecting the man as he goes through his daily routine, his thoughts and opinions. There is casual acceptance of the beauty of a simple life: “I would also wander around when I wasn’t smoking, and look at this and that within a stone’s throw, gaining something every time. If there really wasn’t anything worth seeing, I would go home to resume what I had been doing before.”

There is obvious delight (just see his photographs) in the absurdities and coincidences of Hong Kong’s urban street life. Mercifully, the book is not nostalgic and is centred on the here and now. He doesn’t lament the past, but obviously enjoys the stoic, almost immutable features of Hongkongers and their often gruff, down-to-earth lives and values that may seem quaint, but are still generally and universally held, even by young people.

He loves chance encounters, the brief passing of a shared moment – and, I imagine, just getting on without any baggage after the encounter. He recalls, “A couple of nights ago, when it was windy and rainy, I asked someone for a light outside a cha chaan teng. The old dude gave the flame watertight protection. After the cigarette was lit, he added, ‘As easy as lightning a match’. Now that’s how real people talk; strangers who don’t know Adam have their own ways of conversing.”

There is a lovely interweaving in these stories of his younger self, often briefly mentioned but subtly poignant. In an anecdote about buying fish from a fishmonger, who he says is “a veritable sculptor or installation artist” as he arranges the displayed fish “like a jigsaw puzzle”, he buys a yellow croaker, then at home, “... I ended up polishing off that yellow croaker. I found and cleaned the two ear stones hidden in the fish’s head, and placed them in a glass bottle. When there are enough stones in the bottle, I could seal it and make a rattle or some such, for a child who loves music. I had such a toy when I was little. Back then, eating yellow croaker didn’t require a long journey. It would be there waiting for me, after a sweaty day of play.”

There are few overt references to his artist’s life, but the entire book can be read as an artist’s life. He does relate in the book’s final story, Two Sides of Two Walls, the story of the mural he painted on the back and side wall of Club 71, the bar he regularly played music in, that was run by his friend “G”, as he refers to her in the book. Wong painted over the mural before the bar closed, but the whitewash wasn’t strong enough and the painting reappeared. Some customers tried to further remove the whitewash. Wong’s comment, in reply to a question about whether they were “destroying the painting or preventing [him] from destroying it” was, “Neither: they are being nostalgic about something that has not yet disappeared.”