Reviews & Articles

Non-Contemporary Dance in Contemporary Art: Three Inspiring Video Installations

Erin Yining LI

at 6:16pm on 19th August 2020

Caption:

Rebecca Ann Hobbs, Mangere Bridge; 246 Meters, 2010. Installation view, ‘Wansolwara: One Salt Water’ exhibition, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney, 2020.

All photos: Erin Li Yining

(原文以英文發表,題為〈非當代舞跳入當代藝術的三個案例〉。)

After being wowed by the extremely energetic work of Barbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca at the Brazilian Pavilion at the 2019 Venice Biennale, and beginning to learn street dancing myself, I started to notice the intriguing presence of non-contemporary dance elements in contemporary artwork.

In Hong Kong, as with many other places, curators and artists often turn to contemporary dance rather than other dance genres when organizing crossover projects between dance and contemporary art. When I asked Serge Laurent, a Paris-based curator well-known for cross-disciplinary museum programs, if he had thought about bringing street dance and contemporary art together, he looked puzzled, “no, I have always worked with contemporary dancers. Street dance is for the street, and never meant for museums.”

However, contemporary dance was also not originally imagined to be seen in museums or art spaces; although one of its pioneers, Merce Cunningham, often did collaborate with many celebrated visual artists, including Nam June Paik, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol. The whole point of contemporary art, in my opinion, is to break rules and invent fresh ways to express contemporary thoughts and spirit. As many non-contemporary dance forms, especially street dance, started as vehicles for marginalized voices, a theme often explored in contemporary art, the synergy and collaboration possibilities between contemporary art and those dance forms seem infinite. Below, I introduce three relevant artworks that strongly resonate for me.

Work 1: Rebecca Ann Hobbs, Mangere Bridge; 246 Meters, 2010

I vividly remember a bizarre scene during a stand-off between anti-extradition protestors and the police in Central in June 2019: a man suddenly jumped into an open area on Des Voeux Road and started to breakdance facing the police. After watching Mangere Bridge, 246 Meters by Rebecca Ann Hobbs, I finally came to appreciate the subversive nature of that breakdance in the protest.

In Hobbs’ video, dancer Amelia Lynch crosses the Old Mangere Bridge in a ‘dancehall’ style, as if to measure with her body this 246-metre bridge that connected North and South Auckland in New Zealand* between 1914 to 2018 (and will soon be demolished). Even if you are not familiar with how dancehall first gained popularity amongst working class Jamaicans amid drastic sociopolitical changes in the late 1970s, you would still be able to sense how every roll, pop, and whine shouts out to the whole world (or, at least, to all the fishermen she passed by); a manifesto rising from adverse circumstances, of self-affirmation and empowerment. As she dances forward, she reclaims the public space, both literally and metaphorically, just like the man who mockingly breakdanced during the protest, right in the heart of Hong Kong’s CBD.

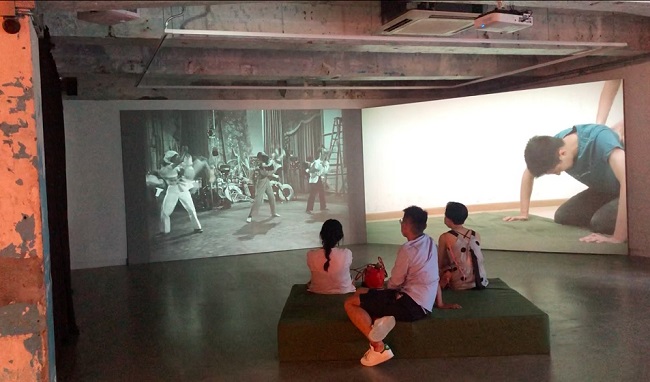

Work 2: Hao Jingban, Opus One, 2020

Hao Jingban, Opus One, 2020, dual-channel video installation. Installation view, ‘Anonymous Society for Magick’ exhibition, Blindspot Gallery, 2020.

Beijing-based artist Hao Jingban never fails to touch me with her rich yet subtle essay films, especially those related to dance. Her new dual-channel video installation Opus One juxtaposes jaw-dropping archival footage of swing dance masters from the 1930s, including Frankie Manning and Norma Miller, alongside the recent journey of a young contemporary Chinese couple’s years long effort in learning ‘authentic jazz’ and choreographing their own piece.

The protagonists Suzy and KC realized that to grasp the essence of swing dance, they needed to have a solid understanding of its origins and philosophy. After watching archival dance videos over and over, they organized swing dance events in Beijing to recreate the 1930s Harlem vibes. They even flew to New York to meet the remaining key figures of the swing dance community from its golden era. Suzy and KC also drew inspiration from viral TikTok dance moves and everyday physical movements by working-class people in their own city, ‘head-rubbing’ for instance, in their own choreographed piece. And above all else, they practiced dancing, over and over. When sitting on the venue’s thick gymnastics landing mat to watch the video, one can imagine how much sweat must have dripped onto Suzy and KC’s own mat!

In this work, dance embodies history and culture. The question whether someone growing up in a completely different era, culture, and class could truly master such a culturally-specific form as this dance genre might anticipate the fundamental questions challenging our world today: the possibility of understanding each other and making deeper connections despite our vast differences.

Work 3: Nicholas Galanin, Tsu Héidei Shugaxtutaan (We Will Again Open This Container of Wisdom That Has Been Left in Our Care) Parts I and II, 2006

Nicholas Galanin, Tsu Héidei Shugaxtutaan (English translation: We Will Again Open This Container of Wisdom That Has Been Left in Our Care) Parts I and II, 2006. Installation view, ‘NIRIN: the 22nd Biennale of Sydney’, 2020.

While Opus One details an odyssey and leaves the audience to judge whether the couple succeed, Tsu Héidei Shugaxtutaan Parts I and II makes a firm statement by presenting a fascinating encounter between street dance and the culture of the Tlingit, a First Nation of the Pacific Northwest coast of North America.

Imagine coming across an over-sized-human projection of hip-hop dance high above eye-level within a pillared archway of the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney. The screen covers half of the adjacent Romantic landscape paintings in the museum’s permanent collection. More arresting than this setup is that the hip-hop dancer David Elsewhere is effortlessly freestyling to a traditional Tlingit song. On another screen in a nearby gallery, a Tlingit man is fully absorbed in his traditional steps accompanied by the beats of electro-dub music. Artist Nicholas Galanin’s intention is to show, and I paraphrase: “non-contemporary cultures are also contemporary.” This is emphasized in the ‘chemistry’ between all the contemporary artwork seen during NIRIN: the 22nd Biennale of Sydney and the museum’s original displays.

Dancehall, swing, breaking, and hip hop - like countless dance forms that have stood the test of time - are charming in an almost paradoxical way: they each radiate a vibe associated with their unique history and traditions, while pushing boundaries to express individuality and a contemporary spirit. When incorporated into/alongside contemporary artwork, dance elements could contribute refreshing views related to individual agency, cross-cultural understanding, and marginalized communities. I cannot wait to see more cross-experimentation from dancers, artists and curators.

*The bridge roughly divides the city into north, which is richer and whiter; and south, predominantly lower-income Maori and Pacific Island communities.

Video links:

Rebecca Ann Hobbs, Mangere Bridge; 246 Meters:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iytm2yy750o&feature=emb_logo

Nicholas Galanin, Tsu Héidei Shugaxtutaan (English translation: We Will Again Open This Container of Wisdom That Has Been Left in Our Care) Parts I and II:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ue30aKV1LF8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vg2c1jtm59o