Reviews & Articles

What is contemporary art? Asia Pacific Triennial, QAGOMA, Brisbane, 24 November 2018 – 28 April, 2019

Helen GRACE

at 1:56pm on 22nd December 2018

Caption:

Jonathan Jones, Wiradjuri/Kamilaroi peoples, Untitled, giran (detail) 2018 Bindu-gaany (freshwater mussel shell), gabudha (rush), gawurra (feathers), marrung dinawan (emu egg), walung (stone), wambuwung dhabal (kangaroo bone), wayu (string), wiiny (wood), 48-channel soundscape / Sound design: Luke Mynott, Sonar Sound Courtesy: The artists and Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Photograph: Natasha Harth, QAGOMA

(原文以英文發表,題為〈什麼是當代藝術?亞太當代藝術三年展,澳洲昆士蘭藝術博物館與現代藝術博物館,2018年11月24日至2019年4月28日〉。)

What is contemporary art? The Asia Pacific Triennial, now in its 9th edition, has arguably done more to debate that question – and to shift its geography – than almost any other institution in the world in the last 25 years.

It’s also led to the revitalisation of Brisbane’s South Bank, with the refurbishment of the Queensland Art Gallery and GOMA (Gallery of Modern Art) building, opened in 2006 for APT5. In art terms, Brisbane is now a more important centre in Australia than Sydney.

APT has had a profound impact, setting up networks of artists and curators regionally and globally. Above all the Queensland Art Gallery’s policy of acquiring many of the works it commissioned built, not only its own collection, but also the major institutional acceptance of a body of work and a whole new generation of artists, whose futures changed as a result.

Major global artists, such as Cai Guo Qiang, were hardly known beyond East Asia until their inclusion in the APT. Prominent Indonesian artists, such as Heri Dono, Dadang Christanto and FX Harsono came to global attention via APT – and there is a long list of such figures.

M+ director, Suhanya Raffel, played a leading role in this world-shifting project and many other curators and directors who are now preeminent figures regionally and globally started out here.

New art from the Pacific, from South East Asia and from what might be called ’West Asia’ featured and the global artworld has been re-oriented as a result. This very reorientation underlined the porosity of ideas about ‘the East’, dissolving borderlines and categories and pushing these boundaries into completely new territories, in inspired curatorial research.

This latest edition foregrounds the Pacific, asking again our leading question of what contemporary art might be. Is the Bougainville and Solomon Islands’ collective Women’s Wealth project art, craft or ethnography or does it challenge these very categories?

Figure 1: Imelda Vaevavini Teqae, building pot Women’s Wealth workshop, Nazareth Rehabilitation Centre 2017, Chabai, Autonomous Region of Bougainville. Photograph: Taloi Havini

Taloi Havini’s remarkable video installation, Habitat, is a core part of this overall project, though it is subsumed under the collective grouping, Women’s Wealth, occupying central place in the Queensland Art Gallery.

This foregrounding of collaborative collectivity is another challenge to the excessive narcissism of individualised creativity, of big, blokey projects occupying vast gallery space.

In the case of Havini’s work here, the space and time of Bougainville has real force in the resonant presence of place and the spectral latency of a ruinous recent history. Habitat is a major highlight of the whole show.

Figure 2:

Figure 3: Taloi Havini, Habitat, 2018 (video stills) Four channel HD, colour, black & white, surround sound, 10''33 digital video installation

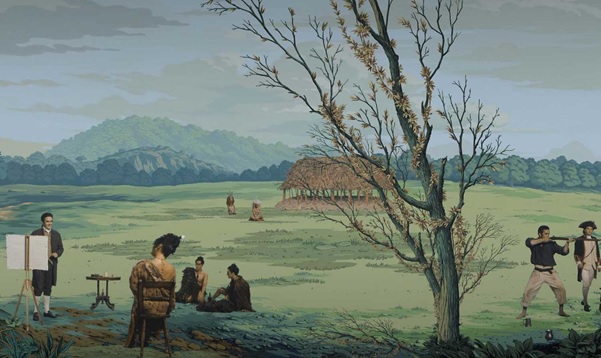

Lisa Reihana’s extraordinary in Pursuit of Venus (Infected) features in GOMA’s APT presentation. This immense panorama reanimates the Naoleonic era neoclassical wallpaper ‘survey’ of Pacific peoples, Les Sauvages de la Mer Pacifique (1804-5), transforming the exoticism of the original and reversing its gaze, displacing the colonizers, discomforted in their occupation. The work is mesmerising in its technical complexity, its pre and post-cinematic extension of the panoramic form, and the magic of its reanimation and wondrous soundscape.

This is the third time I’ve seen this work – firstly in the 2017 Venice Biennale, secondly in the survey of Reihana’s work at Campbelltown Art Centre earlier this year (where it benefited from a more immersive curved screen projection) and now APT, and each time it becomes a more epic and compelling composition.

Figure 4:

Figure 5:

Figure 6: Lisa Reihana, Ngā Puhi, Ngāi Tu, Ngāti Hine, Aotearoa New Zealand b.1964, in Pursuit of Venus [infected] 2015– 17. Single-channel Ultra HD video, 64 minutes (looped) 7:1 sound, colour, ed. 2/5 / Purchased 2015 with funds from the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation Appeal and Paul and Susan Taylor / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery. Photograph: Norman Heke. Images courtesy: The artist.

In what sense is the revival of a traditional craft a contemporary practice? The Jaki-Ed Project, to revive a discarded weaving process in the Marshall Islands, throws up a challenge that goes beyond the formal geometric patterns of the impressive pandanus fibre works exhibited here. Based on the patterns, it seems the word ‘Jaki-Ed’ is derived from ‘jacquard’ – the disruptive automated loom that displaced hand-weaving in the Industrial Revolution. But here, that innovation is wound backwards and the weaving process is ‘rehumanised’ in the women’s weaving circle, rebuilding community in a location decimated by post-war US nuclear testing and more recently calamitous climate change.

Figure 7: Jaki-ed weaving workshop, Majuro, Marshall Islands, September 2017. Photograph: Christine

Germano Image courtesy: The artist and University of South Pacific, Majuro. The Jaki-ed project was developed in collaboration with the University of South Pacific, Majuro and supported by QAGOMA’s Oceania Women’s Fund, enabled by the generous bequest of Jennifer Phipps

Art of course never flies the flag of a particular politics or strategic interest but it’s tempting to consider that the strength of the Pacific presence in this APT coincides with a greater focus on the Pacific in Australian foreign policy. The region, largely ignored by Australian politicians for too long, comes into focus at precisely the time that China’s regional presence is on the increase, requiring greater attention to counter this influence.

Not coincidentally, for APT9 Qiu Zhijie has installed a vast work of ‘modern calligraphy’, (in this, he is an exemplary and pioneering practitioner). The vast mural, Map of Technological Ethics, 2018, continues the artist’s concerns with imaginary geographies and dystopian landscapes and his ‘Total Art’ method probably owes more to Boris Groys’ concept of total art (‘The Total Art of Stalinism’) than to either Wagner’s mythico-religious Gesamtkunstswerk or Alan Kaprow’s 1958 ‘total art’ (a more hippy ‘relational aesthetics’– avant la lettre – than totalitarian).

(For a Timelapse of the installation, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=byy3ewRg_40&feature=youtu.be . For the artist’s discussion of the work and method, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7wwJOw9hULY&feature=youtu.be )

In Asia One, Cao Fei continues her precise observation of the human impact of rapid economic transformation in China in this new ‘logistical sublime’ work. Robots replace workers in the main projection and workers themselves become robots, in the accompanying documentary, 11.11 (Double Eleven – China’s massive one-day online shopping event, held in November; with sales this year in excess of $30billion – over four times the volume of the US ‘Cyber Monday’ Thanksgiving sales).

Figure 8: CAO Fei, Beijing, China b.1978 , Asia One (still) 2018 , HD video installation: 63:20 minutes, sound, colour, ed. 1/8, Purchased with funds from Tim Fairfax AC through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation 2018. Collection: The Queensland Art Gallery

Joyce Ho’s wry, engaging installation proved popular, with a suite of finely installed works, including the ‘interactive’ On the other day, and the forceful Overexposed memory.

Figure 9: Joyce Ho, Taiwan b.1983 Overexposed Memory 2015, Single-channel video installation, 4‘47”. Image courtesy: The artist and TKG+, Taipei

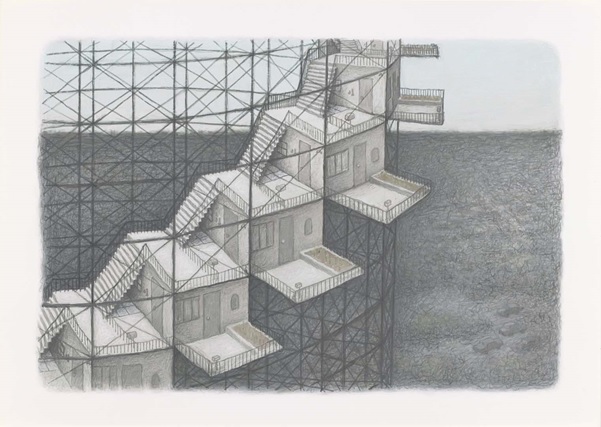

Kim Beom’s wonder-ful fantasy blueprints and perspectives project all-too real imaginary worlds of tyrants and excessive security. This absurdist universe seems all-too present in contemporary culture.

Figure 10: Kim Beom Korea b. 1963 Schematic Draft of a Disconnected Under River Tunnel 2017 Inkjet print on cotton paper, ed. 2/8 (4 AP) / 34.1 x 43.8cm / Purchased 2017. Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation. Collection: Queensland

Figure 11: Residential Watchtower Complex for Security Guards 2017 Inkjet print on cotton paper, ed. 2/8 (4 AP) / 36 x 51cm / Purchased 2017. Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation. Collection: Queensland Art Gallery

Of the patchy painting in the exhibition, the strongest includes Mongolian artist, Enkhbold Togmidshiirev’s large organic abstractions, made of horse dung, mushroom dust, cotton and wax. I can only imagine the epic process of getting these through customs into Australia!

Figure 12: Enkhbold Togmidshiirev, b.1978 Övörkhangai Province, Mongolia. Without form 2014, Horse dung, mushroom dust, cotton and wax on canvas / 280 x 200cm. Coming season 2015 Horse dung, , cotton, wax and hessian on canvas / 280 x 200cm. Mother land 2016 Felt, horse dung, cotton and wax on canvas / 280 x 200cm. Blue Sentient (installation view) 2015. Wooden structure, single channel video / 200 x 200cm. Image courtesy: The artist and Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art. Photograph: Natasha Harth, QAGOMA

Vincent Namatjira’s deliberately awful paintings are pointed in their piercing portrayals of prominent Australians – former politicians, Indigenous leaders, rich people.

Figure 13: Vincent Namatjira, Western Arrernte people, b.1983 Australia. Gina Rinehart (from ‘The Richest’ series) 2016 Synthetic polymer paint on canvas 7 panels: 91 x 67cm (each) Courtesy: The artist, Iwantja Arts, Indulkana Community and This is No Fantasy, Melbourne

Kushana Bush’s revelatory works appropriate traditions beyond the lived experience of the artist, (Japanese woodblock prints, Indian miniatures, Renaissance frescoes), transforming these in ways that are profoundly original and contemporary. If eclectic cultural appropriations frequently seem unthinking or indeed colonising, there is a rare intelligence at work here in intricate compositions, opening out imaginative worlds, that are simultaneously delirious and dystopian.

Figure 14: Kushana Bush, b.1983 Aotearoa New Zealand, Hark 2018, Gouache, metallic paint and pencil on paper / 55 x 68cm. Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art. Image courtesy: The artist and Darren Knight Gallery, Sydney

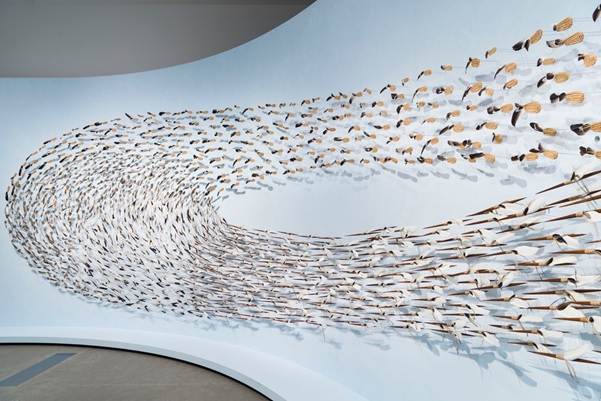

The strongest of the contemporary Australian indigenous work is undoubtedly Jonathan Jones’ breathtaking installation, untitled (giran), 2018. Infinity-shaped, the work, consists of around 2000 finely-crafted individual sculptures, made from indigenous tools used in everyday survival in south-east Australia. The work, made in collaboration with Wiradjuri elder, Dr Stan Grant Snr, floats in a curved space, immersed in a soundscape of whispered Wiradjuri language and resonant ambience (birdsong, wind, breath). To enter is to have a sense of the sweep of migrating birds in flight, and an active and living human world.

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 17: Jonathan Jones Wiradjuri/Kamilaroi peoples Born 1978, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia Lives and works in Sydney with Dr Uncle Stan Grant Snr AM Wiradjuri people Born 1940, Dubbo, New South Wales, Australia. Lives and works in Dubbo (untitled) giran (detail) 2018 Bindu-gaany (freshwater mussel shell), gabudha (rush), gawurra (feathers), marrung dinawan (emu egg), walung (stone), wambuwung dhabal (kangaroo bone), wayu (string), wiiny (wood), 48-channel soundscape / Sound design: Luke Mynott, Sonar Sound Courtesy: The artists and Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Photograph: Natasha Harth, QAGOMA

APT9 Cinema presents two programs of recent features – a ‘New Bollywood’ season and a selection of East Asian melodramas. Highlights include E J-yong’s Bacchus Lady (Jugyeojuneun Yeoja 죽여주는 여자), starring legendary actress Youn Yuh-jung 윤여정.

The program, although impressive in gathering together so many recent features rarely seen in Australia, even in the major film festivals, seems peripheral to the main event – the fate of so much cinema shown in gallery survey show contexts. Yet this season alone is worth the stay in Brisbane.

There is an assurance in APT9 – in selection and installation and overall force - that so clearly marks the distance travelled since 1993’s first tentative steps in this direction. It places Brisbane firmly as a global destination for encountering the most challenging emergent – and established - art in the world today.

©Helen Grace, December 2018