Reviews & Articles

The Hong Kong Contemporary Art Awards 2012

John BATTEN

at 0:00am on 17th January 2014

Captions:

1. So Hing Keung, Now – History, photography, set of 7 pieces, 2011.

2. Rachel Cheung Wai-sze, Fable and Spell II, mixed media (ceramics, rubber bands and paper), set of 8 pieces, 2009.

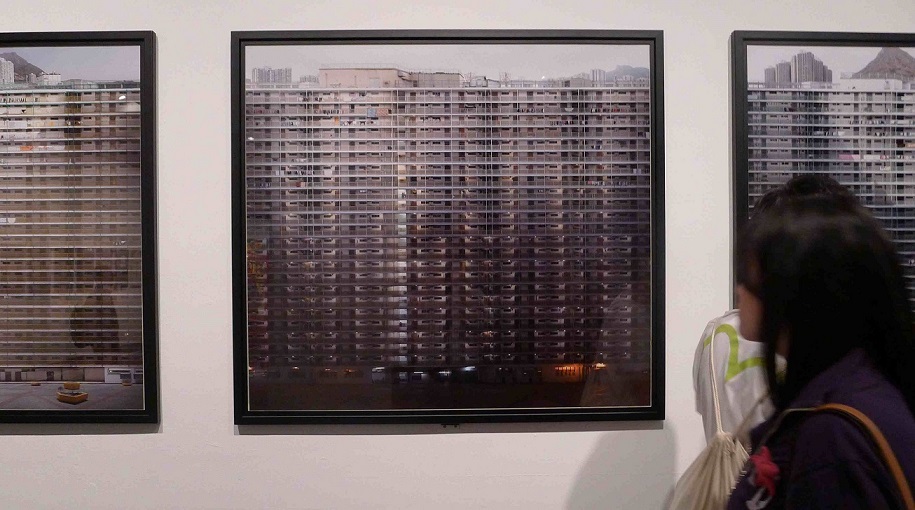

3. Max Chan Wang, Unfolded, photography, set of 3 pieces, 2012.

4. Ho Sin Tung, Inter-vivos Film Festival, mixed media (pencil on paper, videos, chair), installation view, 2011.

5. Hector Rodriguez Gestus: Judex, video, 2011.

(原文以英文發表,評論「香港當代藝術獎2012」展。)

After you enter the Hong Kong Museum of Art, collect a headset to listen to Cédric Maridet’s the sound of art while walking around the museum to view the Hong Kong Contemporary Art Awards. More a series of field recordings inside galleries around the world rather than sound art, Maridet’s piece has the uncanny ability of existentially focusing the Awards exhibition and blocking out all extraneous sound. Through Maridet’s recordings, the museum’s ambience is distorted, replaced by our own thoughts and a concentration on the art.

The work of Kacey Wong dominates the entrance to the Awards. Exhibited are two constructions produced for two performance pieces: a bicycle/bunk-bed for a horizontal lying rider and a mini reproduction of a floatable almost-impossible-to-live-in Hong Kong sized and styled apartment. The latter, Paddling Home, was originally performed at the 2009 Shenzhen-Hong Kong Architecture Biennial, with Wong as the ‘ship’s captain’ to briefly navigate this buoyant apartment on Victoria Harbour. The showing of the documentary videos of these performances could have been improved if accompanied by more information about Wong’s social criticism as art; a significant facet of his recent work.

This year, 91 artists were selected to exhibit at the Awards, which are not a curated exhibition, but comprise competition entries in different categories of individual artwork. This will always limit the Awards’ scope, which began in1975 and are presented every two or three years by the museum’s parent organisation, the Leisure & Cultural Services Department. Under the current format there is scant opportunity to present a wider, more holistic overview of an artist’s recent work.

Alongside Hong Kong’s progress in the art world, an ambitious visual art biennial or triennial should now be an aspiration. The Awards showcase Hong Kong contemporary art, but the time is right for a serious, domestically curated biennial, with invited Hong Kong, regional and international artists exhibiting together. Interestingly, under the terms of Uli Sigg’s donation of mainland art to M+, the current Chinese Contemporary Art Awards, which Sigg began in 1997, will be organised by M+. In the future, we will have two, albeit not necessarily competing, art competitions in our dedicated visual art museums. But, the gap for an invitation-style biennial is waiting to be filled. Could the Hong Kong Museum of Art, M+, or another art organisation fill it? Despite its title, Another Day of Depression in Kowloon, Ip Yuk-yiu’s tableaux of selected sewn excerpts from Call of Duty: Black Oops, a popular animated video game released in 2010, is a beguiling view of Hong Kong. On a rain sodden day, Hong Kong’s unusually empty streets are glimpsed through lightning flashes to illuminate its classic movie-landscape. Ip successfully reworks the original video’s story to distort the action-film stereotype of Hong Kong into the lovingly familiar Kowloon streets known to residents. This understated video is a surprisingly strong call to keep Hong Kong’s unique street ambience over the interests of rapacious redevelopment.

Likewise, the photography of So Hing Keung and Max Chan Wang has a political undercurrent in their presentation. So’s intentionally scratched and degraded images of familiar mainland sites, such as Beijing’s ‘bird’s nest’ Olympic Stadium and the Temple of Heaven, question the touted success of the mainland’s recent economic and geo-political resurgence. Max Chan’s manipulated images of Hong Kong housing estate blocks depict scenes that are impossibly serene and photo-picturesque. More overt is Wong Kwok-pui’s sculpture of a bicycle built within a steel street barrier; a direct expression about Hong Kong’s continuing stifled debate about democracy.

The Awards feature many video presentations. Hector Rodriguez’s Gestus: Judex uses images from Louis Feuillade’s film Judex of 1916 to demonstrate his custom software that draws viewers away from a film’s main narrative involving people, objects and plot to instead “focus on motion as an end in itself.” On a large screen viewers can watch the film, and on a separate monitor are invited to scroll through sequences of the film to isolate and compare similar movement patterns. Rodriguez’s software highlights the numerous and intricate surveillance technologies that the public, unwarily, experience daily. Mimicking the real-life Hong Kong International Film Festival, Ho Sin Tung uses her fictional Hong Kong Inter-vivos Film Festival to mount a subtle critique of the film industry and its rounds of festivals. Her world of film stills, promotional posters, video promo trailers, a daily ‘festival news’ flyer and a brochure of descriptive film synopses is a spoofy, humorous marathon effort of hand-drawn artwork.

Displayed and separately judged in an adjacent gallery is a selection of calligraphy, seal cutting and painting using traditional Chinese media. Without the strong gallery infrastructure that contemporary art has to support itself, it is the traditional arts that – possibly - need the encouragement of these Awards. However, categorization of the arts is limiting. For example, the aesthetics of Rachel Cheung Wai-sze’s Fable and Spell II uses a ‘traditional’ sensibility and media. However, her beautiful counterpointing of porcelain and paper is beyond categorization, despite it being placed in the ‘Western’ section of the Awards.

If there is to be a Hong Kong Contemporary Art Awards, it could be an interesting task in the future to judge ‘Western’ and ‘traditional Chinese’ as one stream, or to initiate two completely independent Awards for each. As it stands, the Awards merely reflect an East-West artistic divide.

A version of this review was published in the South China Morning Post on 23 December 2013.