Reviews & Articles

Undergraduate Graduation Exhibition 2014 at Hong Kong Baptist University's Academy of Visual Arts

John BATTEN

at 9:38am on 27th December 2014

Captions:

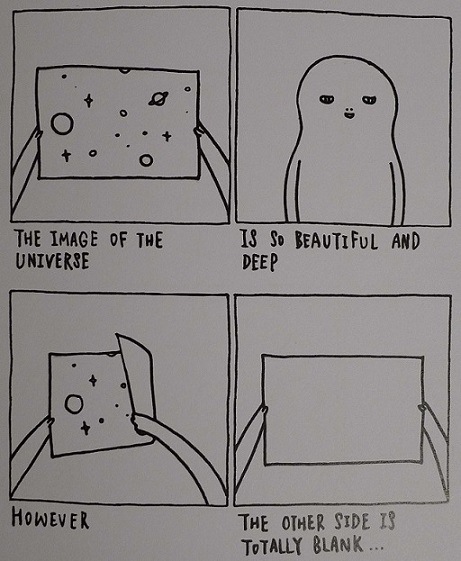

1. Hung Choi Sau, Beyond This series, comics, 23x27cm each.

2. Szeto Wai Yam, Prescription, copper & brass, various jewellery pieces.

3. Cheung Nga Wun, Protest City, illustration, 35x270cm.

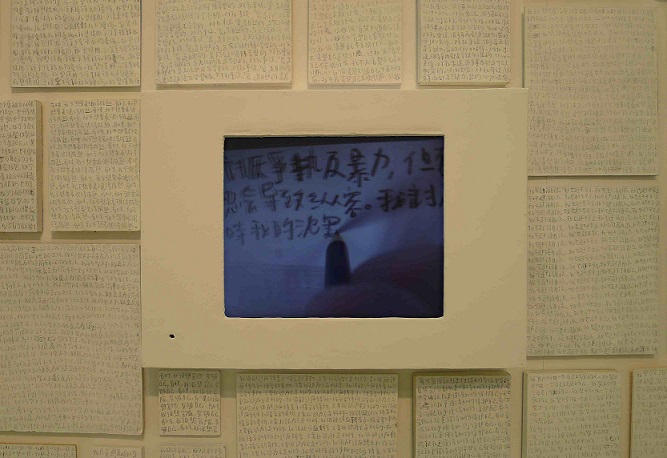

4. Li Xiaohua, Memory Still, installation, gallery installation.

5. Tsang Tsou Choi (King of Kowloon), in situ graffitti in front of HKBU's Academy of Arts.

(原文以英文發表,評論「浸大視藝畢業展2014」展。)

The Hong Kong Baptist University’s Academy of Visual Arts (AVA) is housed in former military barracks previously occupied by British air force staff, at-the-time conveniently located near Hong Kong Airport at Kai Tak. These low-rise colonial buildings have high ceilings, verandahs, long corridors, surrounded by grassy grounds: perfect for arts teaching facilities. It is a unique, spacious and historic venue for students to study in and to host the AVA’s annual graduation exhibitions.

This year, one hundred students’ work was spread throughout the AVA, but the large central gallery was not used as an exhibition venue. It has previously been perceived as the best location for graduates to display their work – in fact, the AVA’s range of large and smaller rooms and some outdoor spaces are all good for viewing. So, this year the central gallery was solely devoted to the opening ceremony and inaugural graduation dinner for students and guests – the dinner is an example of the camaraderie on the AVA campus. Previous graduates are also involved in the graduation exhibition by selecting the winners of the Tuna Awards, originally initiated by former AVA students to give encouragement to new graduates.

This year’s AVA graduation exhibition was well organized and, generally, of a good artistic standard. Art students, not surprisingly, are generally inspired and use their own personal experiences as subjects for their artwork – so, families (particularly mothers!), animals, friends and personal anxieties predominant. This could be limiting, but a graduation exhibition is part of the course requirements and the student will be assessed on technical, conceptual and communication abilities – the chosen subject is almost secondary.

Sweto Wai Yam’s Prescription is an installation mimicking a doctor’s clinic whose individual sculptural components are interpretations of everyday Chinese idioms relating to the body. Many of these idioms are similar across cultures, for example the English and Chinese for ‘lacking backbone’ both describe a person that is weak or unprincipled. Sweto’s ‘prescription’ for attacks of ‘lacking backbone’ is a beautifully constructed brass tubing and leather brace to be worn if you suffer from this debilitating affliction. Sitting beside similar constructions or ‘prescriptions’ was the artist’s name-card (as usually seen at graduation exhibitions) uniquely printed on a wooden tongue depressor, a nice touch in keeping with this medical display.

Hung Choi Sau’s comic drawings have great humanism and his words ring in poetic rhythm for each story, for example: “The image of the universe / Is so beautiful and deep / However / The other side is totally blank.” This four-panel sequence shows a pair of hands hold a drawing depicting the planets and stars in outer space, and ends with the drawing turned over to show the blank back of the paper. Hung uses simple line drawings, and although technically limited, they appropriately complement his current work. Over time, greater technical complexity will inevitably be tackled. This is a minor matter, he already possesses what a cartoonist requires: succinctness, simplicity and a story.

The Bouncy-Bounce by Ng Yik Kwan is a playful installation with a demonstration video nicely housed in a roughly painted enclosure of warehouse shelving. Protruding from a muddy lawn are mushroom-like lumps of painted concrete sitting atop strong springs. The public can jump and bounce (the technique is well explained in the video) on these “bouncy-bounces” – it is a silly and successful interactive installation.

Topical is Cheung Nga Wun’s Protest City. Unfortunately, merely depicting protesters in marches and demonstrators confronting police does not make the work itself a successful banner of protest; despite the artist saying, “…My critical point of view about demonstration culture is expressed in the drawing.” However, the artist is a mere protest step away: offer your excellent graphic skills for a cause!

Li Xiaohua’s Memory Still is a sensitive installation inspired by his grandfather’s (lovingly) sewing of his clothes when he was a child. In a corner of a room was a wall of slipped concrete with an embedded video, pencil markings on the adjacent wall and a converted pedal-operated sewing machine containing self-cast and self-hammered sewing tools: thimble, needles, thread holders. Li’s intention is that “…the trace of the mended object is not only the symbol of care but also a memory container. I want to conserve the memory by representing the mended objects to metal, making it solid.”

I liked the surrealist drawings on wood of Ting Sze Lok’s The Eleplant in the Room and the outlandish pinecones in Ling Ka Wai’s Chinese paintings. And, using the AVA’s baseball court’s lines Poon Ying Tung has successfully subverted the space into a three-dimensional geometric exercise. The raised lines rearing themselves snake-like towards a perceived threat or as Poon explains as a “spatial drawing” that is “apparently pointing at specific features of the surrounding buildings and nature, thus extending the ordinary view….”

Jewellery was well featured in the show. Copper renditions by Ng Yee Ki of people’s physicals features alongside their Polaroid photographs enticed the viewer to compare differences in gender, including observing a subtle sexual frisson. Wong Oi Shan’s needles and lovers’ notes were beautifully simple. And Chan Wing Sze’s Transiency series of jewellery using wooden toothpicks and silver were much sturdier and more stylish than the common toothpick would suggest!

It is a pity that Chan Shun Yi had not sought out and spoken to Wucius Wong (who still mentors at The Chinese University of Hong Kong) to add a personal dimension, rather than entirely using secondary sources for the competent dissertation on Wong’s traditional Chinese ink painting. Yung Sum Yi, however, does take an interactive approach in her study, Art helping with communication: A case study of children with autism, by observing a class of children with autism to study art as a non-verbal communication tool. Both studies could be expanded into more substantial essays or visual presentations.

Michael Cheung’s opportunistic hiring of male models to pose in his nude photographic portraits was bold, but the conceptual idea of “each individual (model) deliberately facing back(wards) invites the audience to mirror themselves” makes this project a stronger art idea by passively including viewers ‘into’ the photographs.

Art graduates around the world now embrace a variety of media into their work – young artists are not bound to remain, for example, just as painters, but will cross media boundaries depending on the material requirements of their art. This is seen in the making of experimental movies; many artists now include video-making as a component of their work because of the simplicity of using digital cameras and computer video programming.

Two covered heads with attached repelling magnets is seen in Choi Nga Man’s Distance is the New Closeness. It is the sort of odd and transfixing video seen nowadays in commercial gallery and public exhibitions. If projected from floor to ceiling it would be perfect for one of the world’s many biennials – this artist will go far! Technically more challenging is Lai Ka Hang’s Soliloquy Inside the Room, a projection and installation showing the façade of a vacant shop in Kowloon City. The shop is seen in different scenes and the physical installation includes blank papers adhered to the wall, which flap in the ‘draught’ as passing buses zoom past (imagined by a recording of street and traffic sounds), actually the wind is provided by an installed fan and the projections include layers of real estate agents’ advertising signs found on all Hong Kong vacant buildings. The shop façade comes to life in this engaging video, and appears to tell its own story as it awaits its future: a new tenant or demolition.

The challenge of living a fulfilling life is promoted in Lo Ying Ting’s Those 60 Years. She depicts, in a cartoonish way, sixty imagined situations that include: “Me with the Dragon Tattoo”; “The Nude Year started, buddy!”; “Be honest, I have wanted to hit you for a long time.” Similarly, Vinci To Sze Wai’s Seize the Day uses stenciled signage to challenge the public to be braver in their lives. Wan Sin Ying’s attempt to write passages with simplified Chinese characters of which he is unfamiliar is a challenge to his own cultural upbringing that habitually uses traditional Chinese ideograms. It is a challenge of mind over habit – a variation on how to navigate life and destiny.

Wan Sin Ying, My Symbol of Thoughts, video, graphite on painted wood, installation

Chang Tsz Hin’s paintings of television personalities in caricature are a marathon of fine depiction: this presentation of 250 pieces is exemplary. As is Wong Ho Yi’s blue-coloured sound and light installation Urban Seabed.

Choi Yi Ting’s bright installation has a cuteness that in the world of ‘serious art’ could be easily dismissed. But, seeing her Desert Island of fantastic animals and an imagined landscape and reading her reasons for undertaking it suggest some of the necessary conditions for being an artist. “I feel content to be alone. I am sensitive of how I touch and feel things. I combine my experiences and imaginations together in order to create my own significant world. Painting and clay-pinching are my main creative mediums. My works build up an imaginary world that invites people to walk into.”

The determination to work hard, often alone, to create another world or space for an audience makes a creative artist.

Postscript:

An art review makes critical comment or explanation about an art exhibition. I predominantly write for the South China Morning Post and usually and purposely choose to write about exhibitions by young Hong Kong artists or significant exhibitions in public spaces. I wish to ‘encourage’ young artists by acknowledging their creativity and work. An art review also has an educative responsibility to the reading audience: I try to tell a reader something they did not know; I try to encourage the reader to see an actual exhibition. I try to encourage looking!

I have never previously written a review of a student graduation exhibition and normally wouldn’t. A graduation show is an academic requirement and not an entirely free setting for an artist. Ideally, I want to see creativity, done in an environment of free choice. A graduating artist will soon step out into the world and make choices about the future and future careers. Some will be artists. And once on the public stage, comment and criticism of the produced art will follow.

One of the AVA’s teachers, Jack Lee, wrote an article in Ming Pao in early July 2014 criticizing the AVA course structure. There was spirited discussion on the House News website about the article’s content and appropriateness of publishing during the graduation exhibition. In late July 2014, House News suddenly closed and the website and all its archived articles disappeared. The history of that discussion also disappeared. It is sobering and depressing that such enthusiastic debate, and its history, has completely gone. It is a reminder that the physical object, the sort that an artist makes, is culturally, socially, politically and historically important. The items that explain a culture are its art, writing and music.

This is affirmed everyday as an AVA student works up the hill from Kwun Tong Road. Outside the AVA are Hong Kong’s only two extant in situ pieces of graffiti by Tsang Tsou Choi, the King of Kowloon. He was not waiting for encouragement or money or appreciation or an art review or a final student assessment. He just did it! Imagine Hong Kong’s recent history without the King of Kowloon’s wild, delusional, imagined, disjointed calligraphy.

This 'review' was originally published in Ava, number 3, 2014 (printed by the Hong Kong Baptist University's Academy of Visual Arts) - a Chinese translation can be read in the publication.