Reviews & Articles

Two animations from two graduation shows: Jess Lau Ching Wa’s 'The Fading Piece' and Wayne Wong Wing Chun’s 'Koon Tong Chronicle'

Yang YEUNG

at 6:31pm on 27th November 2014

Captions:

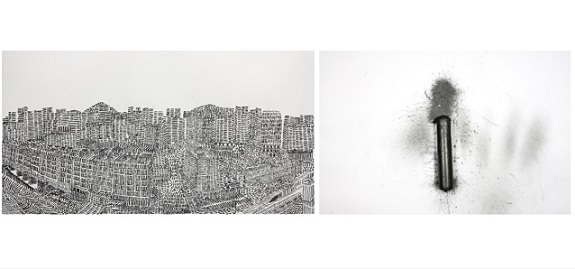

1. - 2. Jess Lau Ching Wa, The Fading Piece, more details:http://cargocollective.com/jesslau/The-Fading-Piece

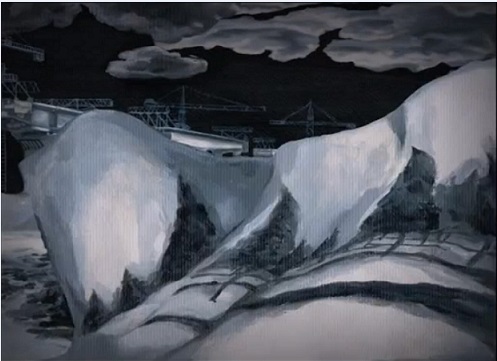

3. - 5. Wayne Wong Wing Chun, Koon Tong Chronicle, more details: https://vimeo.com/wingchunwong

(原文以英文發表,評論劉清華及黃榮臻的畢業作品。)

The Fading Piece by Jess Lau is a duo video installation with sound, presented at City University’s School of Creative Media Bachelor of Arts graduation exhibition. The left projection begins with one short, black stroke on a blank, white screen, followed by a series of strokes of a similar length and weight, extending from the left bottom corner to the right and upper edges of the screen. Buildings, roads, vehicles, bushes…gradually emerge, until an overview of a built topography emerges. The strokes keep reaching up and become broader to sweep the sky.

The video animates a photographic image of the town center of Kwun Tong that Lau found on Wikipedia. Her picturing the image as made up of lines, unfolding in a particular direction and speed, and dissectible by the kind of labor required of the stop-motion technique, reveals crucial aspects of the artistic process – keen observation of the world, patient deliberation about how points of focus recede and arise, and astute interpretation of space as constituted in movements. In deliberately applying discipline and regularity to the strokes to conjure up spatial density and monotony, Lau inscribes not only the presence of the strokes; she also reveals the blankness they are encroaching upon.

The video on the right adds restraint to the process. A charcoal stick as tall as to almost touching the top and bottom edges of the screen begins to vibrate. In brisk, incessant movements, the charcoal stick wears out. When it is no more, the process of inscription on the left also stops; that is, the ending of the video coincides with the natural deterioration of the artist’s material, compelling her labor to stop as well. What come into the narrative are not such meanings from the outside as the contention over urban development or renewal, its capacity to brutalize or destroy etc., but rather, the artist’s quiet reflection and small struggles with what she perceives. In comparison with the wide, overview of the built topography, the charcoal stick is monumental in size. Is it also monumental in meaning? I find Lau’s decision to push the charcoal stick right into the viewer’s face interesting. It directs and diverts the tension built up in the making of density towards the artist’s self-possessed activity. In sustaining the tension, Lau lays open such questions as whether hand gestures of the artist are commensurable with creative and destructive gestures of other kinds.

There could be another reading of Lau’s work: its engagement with time. The animation abstracts what is routinely, speedily, and widely circulated as one among many pieces of visual information into a slow process of materialization in time. I recall experiencing the pleasure of anticipation as the topography unfolds, only to want the drawing to stop as the strokes swipe at the sky and weigh down upon the built topography, as if deliberating whether to erase it or not. This experience would not have been possible if the artist hasn’t had a deep engagement with time as a core material of her creation.

This question of time reminds me of the Industrious Clock by Yugo Nakamura created in 2001. It is still accessible on the internet. It is a set of thumbnail, moving images of a hand, writing with a pencil the second, minute, hour, day, month, and year. The gestures are mechanical, chasing after and failing to match up with clock-time. It suggests how clock-time as spatialized units of time is alienating for the human. Lau shares the sensitivity and interest in how time is mediated by technology and other modes of fabrication. But Lau’s work is also different in that time is not an object to be grasped with a possessive will, but rather, a horizon in which and with which space unfolds.

Wayne Wong takes a different approach in his animation work. Presented at the Baptist University’s Academy of Visual Arts Master of Visual Arts graduation exhibition, Wong’s installation Koon Tong Chronicle is an animation film displayed with a monitor screen amidst some eighty paintings. The paintings are the source materials of the animation film. The paintings spread out into two walls, some reaching up to the ceiling, and others, reaching down below eye level. Without going into the story the work tells – a rich and inspiring mix of ideas addressing fact and fiction, past and future, I would like to quickly raise one question regarding Wong’s conceptualization of space in relation to his preferred art form. The way in which the paintings are displayed certainly yield visual impact. My question is, of what kind is this impact, and what is the kind of attention that the artist wants the viewer to lend to the work?

Listening to Wong speak about his creative process, I am impressed by his willingness to venture into an unfamiliar art form. Although Wong had a solid training in painting, he chooses animation instead for his graduation work because he has become interested in movement. Wong told me how it was during a residency in France not long ago that he realized the activity of wandering without a purpose, choosing and observing an object, and thinking associatively with it, could be very inspiring. In Koon Tong Chronicle, the spontaneity and open-endedness of moving between reflection and materialization seem not to have been given as much place as another kind of creative process: a storyboard trying to break out of its linearity by being laid out in space. As a display of the process and results that serve the production of the animation film, the installation hides the nuances of Wong’s ways of seeing. While it is always rewarding to learn of the multiple origins and muse of an artist’s work, it is equally rewarding to engage with how an artist plays with showing and hiding the boundary of his/her work.

Lau regarded her work as a documentation of energy. By extension, I would propose that both her work and Wong’s are documentations of the distribution of energy in multiple sets of material and symbolic mechanisms, and by doing so, leaving different and interesting questions on what artists can do unresolved and productively open. I wonder how they will take this tandem of certainty and doubt into the future.

First published in AM Post, Hong Kong, November to December 2014.

|

|

|

|

|

|