Reviews & Articles

《疫年日志》短評 After the Plague

Phoebe WONG

at 11:00am on 15th May 2014

圖片説明 Captions:

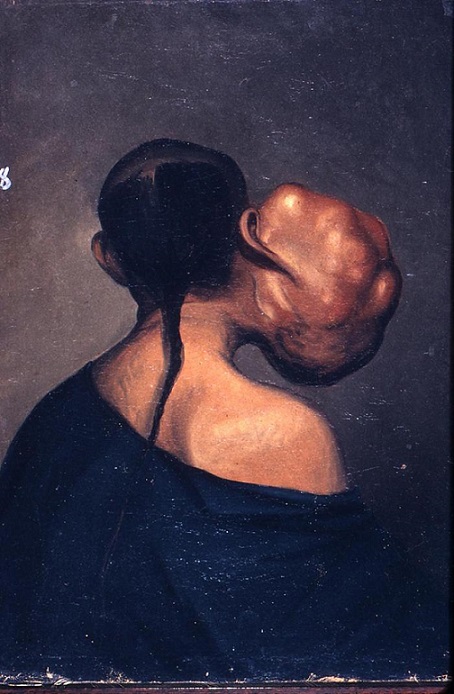

1. Lam Qua, Portrait no 48. Yang Kang, 1830-1850. Oil painting. Photo courtesy: Yale University, Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library. Yang Kang (1830-1850) 林官,〈肖像第48號〉。影像提供:耶魯大學 Harvey Cushing / John Hay Whitney 醫學圖書館。

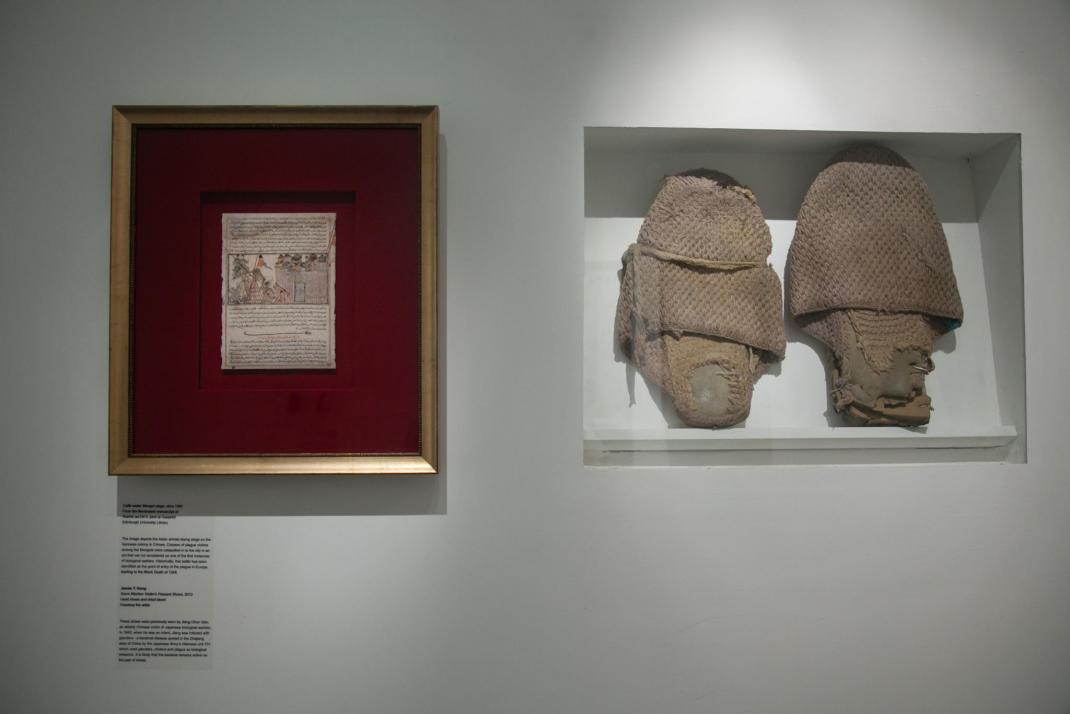

2-4. Installation view of the exhibition. Photo courtesy: Para Site Art Space, 2013. 展覽現場。影像提供:Para/Site 藝術空間。

(英文版請往下看 Please scroll down to read the English version.)

由Para Site 藝術空間執行總監Cosmin Costinas 夥拍獨立策展人兼藝評人Inti Guerrero共同策展的《疫年日志:恐懼、鬼魂、叛軍、沙士、哥哥和香港的故事》,是一檔研究主導、層次豐饒的視覺藝術展覽,香港近年少見。展覽取名援用丹尼爾‧迪福﹝1660-1731﹞於1722年發表的小說《大疫年日志》。這本書描述1665年大瘟疫襲擊下的倫敦城,迪福為求效果逼真,「鉅細靡遺地描述具體的社區、街道,甚至是哪幾間房屋發生瘟疫。此外,它提供了傷亡數字表,並討論各種不同記載、軼事的可信度。」﹝註1﹞《大疫年日志》夠竟純屬杜撰抑或是有根有據的歷史書寫,在書成的18世紀一直有所爭議;要到19世紀初有「歷史小說」體出現,文學評論者便將它看成是一部充滿想像力的「歷史小說」。﹝註2﹞從這角度看,展覽挪用「歷史小說」體的格局,推演歷史是挖掘還是建構的辯證;而文獻與當代藝術作品並置,引領觀者在虛實間遊走,在感官和思辨中探索。至於展覽的意識流副題,串燒出港人深刻的集體烙印、共同記憶:煲醋、口罩、被隔離、淘大花園、「死好多人」、疫阜、哥哥張國榮自殺、反二十三條、七一、五十萬……。經歷了2003年,香港已經不一樣!?

展覽掌握了扣連着沙士創傷與哥哥自殺的不解之迷所揪結出的haunting意象,正如洛楓所說,哥哥的身死,成了傳奇,「SARS的時代創傷與他已是血肉相連」,﹝註3﹞展覽的故事便這樣展開。黎清妍一幅幅面容模糊、人影落寞孤寂的畫作;哥哥的演藝身影﹝雜誌剪報唱片高跟鞋﹞;美國電影《Vanilla Sky》那幕日光日白男主角迷失於空無一人的紐約街頭,片段在重覆播放中更形詭異;1894年瘟疫的歷史檔案老照片;攝影師Bernd Behr捕捉﹝2003-2007年﹞淘大花園SARS現場,電影般的空鏡,凝聚揮之不去的陰霾;一對中日戰爭遺留下來、沾有血跡的草鞋,是日軍731部隊細菌戰的證據﹝洪子健研究後收藏﹞;19世紀中,林官﹝亦寫啉呱,原名關喬昌﹞以藝術肖像方式處理的病理記錄;《霸王別姬》電影片段;王浩然的吻雞行為,與「禽流感帶菌體」作親密接觸﹝〈吻雞〉2007﹞;白雙全的七一遊行﹝報紙作品﹞;……。展覽文獻、作品的鋪展,各自表述卻又互有關聯,有詩的跳躍。

詩人、文化評論人兼「戲迷學者」(註4)洛楓對張國榮的深度研究,有戲迷義無反顧的耽溺(洛楓追隨張二十多年),更有學者論證分析的鞭辟入裏。洛楓眼裏的哥哥是一只「禁色的蝴蝶」,指出「張的精緻、脆弱、斑斕、玲瓏、驕傲和喧鬧,但卻是被禁絕、禁忌和禁棄的色彩,這色彩不流於世俗,所以為世不容」。(註5)接洛楓分析,在身體/性別政治的層面,張是異色的。一切由名字開始,張洋名 Leslie,是個可男可女的中性名字,標誌其性別意識的取向;再者,就是他自身的色相條件:「男身女相」、帶有「屬於上層階級的貴族氣質」、「眉梢眼角盡是風情」、「陰柔的嬌美」;而更重要的是,張具有「演員作者」﹝actor-auteur﹞的主體意識,在他1990年代初復出後的演藝生涯,操演、挪移、轉化性別的邊界,顛覆世俗僵化的性別約束:演唱會上雌雄同體的扮裝,透過易裝「游離於性別的邊界之間」,而張也竭力爭取電影《霸王別姬》裏乾旦「程蝶衣」這個角色,而戲裏張的演繹卻顛覆了這部電影潛藏的恐同意識。張的藝術創造性及破格之處便在於此!(註6)

閱讀洛楓對張的藝術位置的論述,我自動跳接到另一詩人梁偉詩評進念二十面體2009年在港﹝再度﹞搬演元朝鍾嗣成所著雜劇《錄鬼簿》時的體晤:「『鬼』作為人間『邊緣』化的精神意識,鍾嗣成《錄鬼簿》所指向的其實是較諸『中心』(主流知識/價值體系)更具滲透力的藝術媒介。」(註7)貴為亞洲演藝界天王、萬人迷,處於邊緣化的哥哥仍找不到真正的歸屬。

而強烈的主體意識必然催生他者恐懼與邊界焦慮?香港藝術家楊秀卓的〈人與籠〉(1987),塗上野獸油彩,赤裸上身,自困在籠子裏48小時的行為,直喻九七過渡時期港人對前途──融入中國──的擔憂和恐懼。中、港千絲萬縷的連繫與矛盾,無法割斷又不易化解,近年反映在邊界奶粉水貨活動與堵截雙非孕婦來港產子等事件之上。港人於2013年初刊登整版報紙廣告反大陸雙飛孕婦來港產子,更以蝗蟲來比喻雙非兒童!1894年香港爆發鼠疫,由是產生的「鼠疫和亞洲的曖昧聯想,並加劇當時歐美的『黃禍』反華恐慌」的那段歷史,﹝註9﹞香港是白過了?。楊嘉輝的聲音拼貼作品〈暴力邊界〉(2012-13),他身體力行,想在中、港邊境禁區消失前,去收錄實體邊境隔離鐵絲網振動產生的聲音及深圳河的聲音,從而反思更具阻礙力的意識形態、文化價值的無形圍牆、隔閡。而美籍華裔藝術家洪子健的錄像〈台北101:病徵紀實〉(2004),敘述一位亞裔美國人在台灣的尋根之旅中,「意外的發現台灣的文化意識被美國文化明顯而強勢的侵略,並沾污成為全球化、美國化、資本主義化、以及跨越國際的白人強權。」﹝註8﹞〈病徵紀實〉拍於SARS期間,影片的畫外音咳嗽聲,聲聲入耳,成了「被攻陷」的隱喻。

2013年,沙士十年、哥哥逝世十年、「七一」十年,當年的堆疊記憶會如何沉澱?表象物換星移的背後,有些東西仍在循環往復?叫人恐懼的不全然是瘟疫的蔓延,而是被遺忘所侵蝕!本地小說家董啟章1997年創作的《地圖集》,有〈太平山的詛咒〉一章,﹝註10﹞讀後良久未能釋然!

「太平山的悲痛歷史遂埋藏於卜公花園的鳥語花香之下,巨大的榕樹鎖住了死者的陰魂,祥和的根鬚驅除了腐敗的氣息,一切也正如此地的名字一樣得到應驗。自此太平就像瘟疫一樣的蔓延,侵蝕着維多利亞城居民的記憶,並且把遺忘的症狀遺傳給後代,以致後來有人開始不相信太平山曾經是他們前人的家園,就像他們不知道全城最早的慈善機構東華醫院的好些總理是鴉片煙商一樣。其中只有少數人執迷於太平山的故事,但他們已經沒法在地圖上找到缐索。」

註:

1. http://zh.wikipedia.org/zh-hant/大疫年日记。 查閱日期:2013年6月20日。

2.歷史小說「遵照歷史事件和人物進行鋪展描述的書寫體,可適當虛構,故事主線順應歷史發展方向,一定程度反映了歷史時期的社會面貌。」參見:http://zh.wap.wikipedia.org/zh-hant/历史小说。查閱日期:2013年6月20日。

3.這是 Para Site訪問洛楓的錄像裏娓娓伸述的觀點。此句引則自洛楓研究哥哥的專論《禁色的蝴蝶:張國榮的藝術形象》﹝香港:三聯書店,2008﹞,頁22。

4.「戲迷學者」(fan-scholar) 是劇評人、學者盧偉力對洛楓的戲稱,她欣然接受。

5.《禁色的蝴蝶》,頁25。

6.參見:《禁色的蝴蝶》。

7.http://leungjass.blogspot.hk/2009/05/blog-post.html。查閱日期:2013年6月20日。

8.http://urbannomadfilmfest.blogspot.de/2009/12/blog-post_08.html。查閱日期:2013年8月15日。

9.展覽冊子。

10. 策展人把〈太平山的詛咒〉印刷成小本子,在展場派發。

原文中文版刊於亞洲藝術文獻庫網絡期刊《搜記》第三期,2013年。

After the Plague

Phoebe WONG

The exhibition A Journal of the Plague Year: Fear, Ghosts, Rebels, SARS, Leslie and the Hong Kong Story takes its name from A Journal of the Plague Year, a novel published in 1722 by English author Daniel Defoe (1660-1731) which depicts London under siege by the plague that struck the city in 1665. ‘Defoe goes to great pains to achieve an effect of verisimilitude, identifying specific neighborhoods, streets, and even houses in which events took place. Additionally, [the book] provides tables of casualty figures and discusses the credibility of various accounts and anecdotes received by the narrator.’ [1] Whether the Journal should be regarded as fiction or as an historical account with facts to back it up was a controversial subject in the eighteenth century when the book was published. With the appearance of the new genre of the ‘historical novel’ early the following century, ‘other literary critics have [since] argued that the work can indeed be regarded as a work of imaginative fiction, and thus can justifiably be described as an “historical novel”.’ [2] Seen from this perspective, I would say the Para Site exhibition has appropriated the historical novel form to explore the dialectics of history writing and its oscillations between the excavation and construction of evidence. Documents, ephemera, and contemporary works of art are displayed side by side to guide the viewer in and out of two worlds: one solid and the other floating, engaging sensory as well as reflective faculties in an exploratory experience.

The subtitle of the exhibition works as a montage of sorts and speaks to a chain of events that forms people’s collective memories: boiled vinegar, face masks, quarantines, Amoy Gardens, death tolls, an infected city, Leslie Cheung‘s suicide, 500,000 people coming together to rally against Article 23 on July 1.... And thus Hong Kong is changed…

Fundamental to the exhibition is the evocation of the haunting imagery brought on by the traumas of SARS and Cheung’s suicide. In the words of Natalia Chan, Cheung's death became a legend: ‘the tragedies and damage of the SARS epoch are infused into his flesh and blood.’ [3] The exhibition abounds with documents and works that stand on their own right and yet engage in dialogues with one another that bring them into being poetically. Abandoned and shadowy souls are depicted in paintings by Firenze Lai. Magazine clippings, music albums, and stiletto heels cobble together portraits of Leslie Cheung in show business. An eerie scene from Vanilla Sky of the male protagonist lost in broad daylight on empty New York streets plays over and over again in a never-ending loop. Historic photographs of 1894 plague cases serve as reminders of past epidemic horrors. Stills ingrained with murkiness by photographer Bernd Behr (2003-2007) capture the SARS site at Amoy Gardens. A pair of blood-stained straw shoes – remnants from the Sino-Japanese War – evidence the biological warfare waged by the Japanese Army's 731 battalion (collected by James T Hong). The medical pathology records of mid-nineteenth century Lam Qua (whose original name was Kwan Kiu Cheung) are treated as artistic portraits. Select cuts of the movie Farewell My Concubine play. Adrian Wong's chicken-kissing photo defies the inherent threat posed by intimate contact with the SARS host (Chicken Kiss, 2007). Tozer Pak’s July 1 protest march (from his works that appeared in newspapers) is documented.

Poet, literary critic, scholar, and cinephile Natalia Chan undertook in-depth studies of Leslie Cheung, demonstrating the indulgence and obsession of a fan (Chan followed Leslie for over 20 years) as well as presenting cogent arguments and analyses that had taken her deep into the nooks and crannies of Cheung’s life. In her eyes Cheung was a ‘butterfly of forbidden colours’, ‘his delicateness, vulnerability, glamour, luminosity, pride, and loudness representing a forbidden, foreboding, forbidding, and discarded type of colour that is not of this conventional world, and [is hence deemed] unacceptable.’ [4] In Chan's analysis, Cheung was a forbidden colour in body and gender politics. Let’s begin with his name: Cheung’s English name, Leslie, is gender-neutral, therefore flagging his gender orientation. Then one can consider his sensuous and exquisite looks: a male body with female sensibilities, an air of nobility belonging to the upper class, a gaze that sends come-hither signals, a delicate beauty denoting a tenderness that is completely feminine. More importantly, with his actor-auteur consciousness, Cheung brings forth his own subjectivity. In the early 1990s Cheung made a comeback in show business, taking on roles that challenged him in every sense, roles that were acrobatic and gymnastic, floating around the transgender margins and subverting the rigidity of conventional rules about gender and sexuality. In his concert his attire was at once male and female. Through costume changes, he roamed the in-between frontiers of the two genders. He made the utmost effort to fight for the leading female-portrayed-by-a-male role in Farewell My Concubine. However, with his performance he successfully subverted the homophobia inherent in the movie, reaffirming his artistic talent and his out-of-the box creativity. [5]

Reading Natalia Chan’s appraisal of Leslie Cheung’s achievements and position as an artist reminds me of the insight offered by poet and critic Jass Leung, who reviewed the reprised performance of the Yuan dynasty opera The Logbook of Ghosts by Zuni Icosahedron in 2009, and argued that ‘ghosts [are] a spiritual consciousness that exist in the margins of the human world, [and that] the Yuan opera points to an artistic medium that has more penetrating power than mainstream knowledge and value systems.’ [6] Despite being one of the few pan-Asian superstars and an idol to millions, Cheung, in the margins, never found out where he truly belonged.

An overly strong sense of subjectivity naturally induces in others the fear and anxiety of being marginalised. Hong Kong artist Ricky Yeung’s performance, Man and Cage (1987), featuring him bare chested, painted with oils, and caged for forty-eight hours, speaks directly to the fears and worries of Hong Kong people about integration with China during the 1997 transition. China and Hong Kong are immensely and intensely bound, and in conflict that cannot be untangled or resolved easily. The serious problem of parallel imports of baby milk formulae at the border and the influx of pregnant Chinese mainlanders on return visas entering Hong Kong to give birth, are reflections of these fears and worries. In 2013 Hong Kong people put an advertisement in the newspaper to object to the visits of these pregnant women on return visas; they even compared these women’s children to locusts. The plague overtook Hong Kong in 1894, giving rise to ‘a dubious association of the disease with Asia and heightening the “yellow peril” scares in Europe and America at the time.’ [7] Have Hong Kong’s trials been in vain? Liquid Borders (2012-13), an audio collage by local artist Samson Yeung, is a first-hand attempt by the artist to record, on location, the sounds of vibrations of the metal fence at the border and of the Shenzhen River, before the disappearance of the restricted area at the border between China and Hong Kong. In Yeung’s mind, more obstructive than the physical fence is the invisible wall of cultural values, attitude, and consciousness separating the two places. Taipei 101: A Travelogue of Symptoms (2004) by American-Chinese artist, James T Hong, is a video production about the experience of an American-Chinese finding his roots in Taiwan, ‘discovering to his surprise [that] Taiwanese culture has apparently been invaded forcefully by American culture, and has become so polluted that it’s been globalised as well as Americanised, appropriated by capitalism and cross-border white supremacy.’ [8] A Travelogue of Symptoms was shot during the period of SARS; in the film the off-camera coughing sounds become a metaphor for the ‘invasion.’

In 2013, ten years after SARS, Leslie Cheung’s passing, and July 1, how do these layered memories resonate? Underneath all the changes, does anything remain or repeat itself? What seems most disturbing is not always the plague but the amnesia. In Hong Kong novelist Dung Kai Cheung’s Atlas (1997), a chapter entitled ‘The Curse of Tai Ping Shan’ [9] keeps readers contemplating long after they put the book down.

The sad history of Tai Ping Shan was then buried under the flowers and birdsong of Blake Garden. Giant banyan trees locked in the souls of the dead, their benign roots driving out putrid vapours so that everything implied by the name ‘Peace Mountain‘ came true. From then on peace spread as widely as the plague had once done. It eroded the memories of Victoria’s inhabitants, while also bequeathing the symptoms of forgetfulness to later generations, so that people eventually began to doubt that Tai Ping Shan had been the home of their forefathers, just as they also failed to realise that many directors of the earliest charitable institution in the entire city, Tung Wah Hospital, had been opium merchants. A small number still obstinately believed in the story of Tai Ping Shan but were no longer able to find any clues to its existence on maps.

Footnotes:

[1] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Journal_of_the_Plague_Year (Accessed on 20 June 2013).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Natalia Chan, Butterfly of Forbidden Colours: The Artistic Image of Leslie Cheung, Joint Publishing, Hong Kong, 2008, p 22. (In Chinese)

[4] Chan, p 25.

[5] Chan.

[6] http://leungjass.blogspot.hk/2009/05/blog-post.html (Accessed on 20 June 2013).

[7] http://urbannomadfilmfest.blogspot.de/2009/12/blog-post_08.html (Accessed on 15 August 2013).

[8] See A Journal of the Plague Year exhibition brochure.

[9] Dung Kai Cheung, ‘The Curse of Tai Ping Shan,’ Atlas, Dung Kai Cheung, Anders Hansson, and Bonnie S McDougall, trans., Columbia University Press, New York, 2012. Para Site has reprinted the chapter in chapbook format and distributed it as a free artwork at the exhibition.

This article first appeared in Field Notes, Issue 3, October 2013. Field Notes is an online journal published by Asia Art Archive.