Reviews & Articles

Philippe Ramette

Yang YEUNG

at 12:52pm on 16th July 2011

Captions:

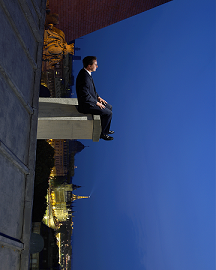

1.Untitled, In Praise of Laziness 1. ©Philippe Ramette. 2000. Photographer: Marc Domage. Courtesy of galerie xippas and Le French May.

2.Irrational Contemplation. ©Philippe Ramette. 2005. Photographer: Marc Domage. Courtesy of galerie xippas and Le French May.

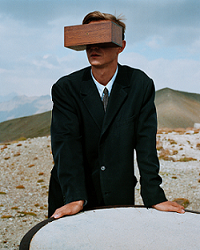

3.Object for Seeing the World in Detail. ©Philippe Ramette. 1990‐2004. Photographer: Olivier Antoine. Courtesy of galerie xippas and Le French May.

4.Irrational Walk. ©Philippe Ramette. 2003. Photographer: Marc Domage. Courtesy of galerie xippas and Le French May.

5. Photographic Metaphor. ©Philippe Ramette. 2003. Photographer: Marc Domage. Courtesy of galerie xippas and Le French May.

(原文以英文發表,評論《菲臘.哈密特那顛倒的世界》展覽。)

Philippe Ramette’s works are daring. They dare viewers to confront his individuality as trivial moments of fantastic logic, to which he has given many names: laziness, irrational contemplation, levitation, lovestruck... They also dare viewers to regard his acts as pathetic – meticulous artisanship put to uselessness. Quietly and firmly, he risks his self being disregarded altogether.

But what of this individuality that compels attention in a thematized tourist territory designed for regulated and standardized consumption – the Avenue of Stars? The Victoria Harbor has always been complicit in the politics of representing Hong Kong. Framed countless times in real estate advertisements and as backdrops of firework extravaganzas, the harbor is made panorama, promising a lopsided success story for a select few. Ramette’s works scorn the view by asking what is missing. This is not only a question of the habor view, but of the artist’s world in general, driven by the conviction to include.

One image captured me first – a white, round balloon leashing the artist’s head, holding it up. The prosthetic in Untitled, In Praise of Laziness 1 (in use) registers the artist’s need for help to stay still, no easy task for any artist condemned to fantasizing while reasoning. The moment parallels the stillness of a dense forest immersed in fog. In a similar way, taken-for-granted habits of such ordinary postures as standing, sitting, lying down, looking afar, reaching up and out with her arms, etc. are all shaken up. In Loverstruck Armchair, one of the only two works in this exhibition picturing persons in addition to the artist, Ramette and his (or as) companion sits on a conjoined wooden armchair facing opposite directions, which vaguely brings to mind the Roman myth of Janus, portrayed in sculptures as two faces of one head facing opposite directions. However, Ramette’s performed double differs from the temporal tension of origin and transition in Janus, in that it is a moment shared in reticence. With silence, Ramette conjures up a situation in line with Martin Heidegger’s idea of being-with-one-another as an ability and disposition to discover one another in the world, from which responses are evoked. Silence is a preparation for something else, while also rich in itself. Hence, the individuality Ramette works with is not an aggressive or acrobatic kind (although the process of making these acts and images, which the artist has generously and openly revealed, require quite a lot of physical strenuousness and endurance). It is rather a compulsive individuality that gets at each one of us once in a while. We are told it is too trivial, too imperfect, to be worth sharing. Ramette says otherwise, and brings it back into life.

Consider the series of works as a whole – a voice whispers. As Ramette looks into an elsewhere, we are reminded of the lost cause of utopics as a way of articulating contemporary art today – hoping that the future can be brought about by the solidarity of given identities is no longer a viable kind of politics in a totally urbanized and capital-driven society. But utopics isn’t about the future, as William P. Weaver, editor of Thomas More’s Utopia reminds us. Utopics is an intervention in time, against homogenization by continuing to do what one must despite continuous time. Louis Marin, in Utopics, says utopic discourse is the expression of the neither-nor. While utopia is no-place, to insist on the concrete possibility of imagining utopics is to affirm the value of a society of self-lovers. Self love must be distinguished from selfishness. Self love is a matter of living life well as an end in itself; selfishness is a matter of gaining goods and pleasures that are means to other goods and pleasures. By looking into the elsewhere, and including us into the act of looking, Ramette, too, contributes to utopics by revealing barriers that have kept us from loving ourselves, living our lives well. He disturbs the barriers, and in so doing, he dares us.

If Ramette at the edges distracts us, look again. By letting entire cities and landscapes encroach upon him, he conjures up single uncompromising moments of precision, only to dream, invent, test, fail, and try again. His insistence on precision is a pursuit for perfect pitch, which Roland Barthes describes in The Neutral as an authenticity in a real relation to others, with oneself and with death, in “desperate vitality.” Christian Bernard, former director of Villa Arson where Ramette studied in the 1980s and kept his studio, puts it well, “Ramettean Man is moral, he knows he is weak and mortal, his is well aware of the common illusions and attempts to correct some of his inborn defects.”

One night, at the Avenue of Stars, a little boy walked past Ramette’s works. He asked his father, “Are these real?” His father said, “Of course not! How can anyone stand like that? They are all digital effects.” This is the kind of parenting one encounters once in a while in the open. This lazy kind of parenting misses one central value of art making - engendering an escapism that Italo Calvino describes as positive and desirable if you were a prisoner who wanted to be free. For the writer, the prison is an amalgam of clichés and received representations. He must plan an escape. Calvino says, “To plan a book – or an escape – the first thing to know is what to exclude.” Ramette excludes the received terms on which life is examined by including a particular slice of rationality, one way of constituting and impregnating the world, that one can have no objection.

The Upside Down World of Philippe Ramette intervenes not just a site, but lives that are averaged out and fenced up in skyward urban spaces. Ramette is not a hero of grandiosities, but our neighbor, sharing with us states of serenity hewn out from the mess. This life, he says, is mine and yours, too. It is embarrassing; it is uncompromising.

To quote Calvino again, “Utopia feels the need for compactness and permanence in opposing the world it rejects, a world that presents an equally refractory front.” Ramette’s works exude compactness and permanence as the “‘absolute rejection’ by means of a world thought out in all its details according to other values and other relationships.” On the opening day, I asked the artist perspiring in a dark blue suit (it was too dark to figure out if it was blue or grey…but it was dark, for sure) what he thinks of utopia. He says, “I like it.”

I can imagine Ramette traveling light, air-borne and all that he is.

Exhibition: The Upside Down World of Philippe Ramette

Date: 28.4. – 29.5.2011

Venue: Avenue of Stars, Tsim Sha Tsui Outdoor exhibition

Website: http://www.frenchmay.com/events/visual-arts

This essay was originally published in the July issue of AM Post.

原文刊於《AM Post》2011年7月

1.Untitled, In Praise of Laziness 1. ©Philippe Ramette. 2000. Photographer: Marc Domage. Courtesy of galerie xippas and Le French May.

2.Irrational Contemplation. ©Philippe Ramette. 2005. Photographer: Marc Domage. Courtesy of galerie xippas and Le French May.

3.Object for Seeing the World in Detail. ©Philippe Ramette. 1990‐2004. Photographer: Olivier Antoine. Courtesy of galerie xippas and Le French May.

4.Irrational Walk. ©Philippe Ramette. 2003. Photographer: Marc Domage. Courtesy of galerie xippas and Le French May.

5. Photographic Metaphor. ©Philippe Ramette. 2003. Photographer: Marc Domage. Courtesy of galerie xippas and Le French May.

(原文以英文發表,評論《菲臘.哈密特那顛倒的世界》展覽。)

Philippe Ramette’s works are daring. They dare viewers to confront his individuality as trivial moments of fantastic logic, to which he has given many names: laziness, irrational contemplation, levitation, lovestruck... They also dare viewers to regard his acts as pathetic – meticulous artisanship put to uselessness. Quietly and firmly, he risks his self being disregarded altogether.

But what of this individuality that compels attention in a thematized tourist territory designed for regulated and standardized consumption – the Avenue of Stars? The Victoria Harbor has always been complicit in the politics of representing Hong Kong. Framed countless times in real estate advertisements and as backdrops of firework extravaganzas, the harbor is made panorama, promising a lopsided success story for a select few. Ramette’s works scorn the view by asking what is missing. This is not only a question of the habor view, but of the artist’s world in general, driven by the conviction to include.

One image captured me first – a white, round balloon leashing the artist’s head, holding it up. The prosthetic in Untitled, In Praise of Laziness 1 (in use) registers the artist’s need for help to stay still, no easy task for any artist condemned to fantasizing while reasoning. The moment parallels the stillness of a dense forest immersed in fog. In a similar way, taken-for-granted habits of such ordinary postures as standing, sitting, lying down, looking afar, reaching up and out with her arms, etc. are all shaken up. In Loverstruck Armchair, one of the only two works in this exhibition picturing persons in addition to the artist, Ramette and his (or as) companion sits on a conjoined wooden armchair facing opposite directions, which vaguely brings to mind the Roman myth of Janus, portrayed in sculptures as two faces of one head facing opposite directions. However, Ramette’s performed double differs from the temporal tension of origin and transition in Janus, in that it is a moment shared in reticence. With silence, Ramette conjures up a situation in line with Martin Heidegger’s idea of being-with-one-another as an ability and disposition to discover one another in the world, from which responses are evoked. Silence is a preparation for something else, while also rich in itself. Hence, the individuality Ramette works with is not an aggressive or acrobatic kind (although the process of making these acts and images, which the artist has generously and openly revealed, require quite a lot of physical strenuousness and endurance). It is rather a compulsive individuality that gets at each one of us once in a while. We are told it is too trivial, too imperfect, to be worth sharing. Ramette says otherwise, and brings it back into life.

Consider the series of works as a whole – a voice whispers. As Ramette looks into an elsewhere, we are reminded of the lost cause of utopics as a way of articulating contemporary art today – hoping that the future can be brought about by the solidarity of given identities is no longer a viable kind of politics in a totally urbanized and capital-driven society. But utopics isn’t about the future, as William P. Weaver, editor of Thomas More’s Utopia reminds us. Utopics is an intervention in time, against homogenization by continuing to do what one must despite continuous time. Louis Marin, in Utopics, says utopic discourse is the expression of the neither-nor. While utopia is no-place, to insist on the concrete possibility of imagining utopics is to affirm the value of a society of self-lovers. Self love must be distinguished from selfishness. Self love is a matter of living life well as an end in itself; selfishness is a matter of gaining goods and pleasures that are means to other goods and pleasures. By looking into the elsewhere, and including us into the act of looking, Ramette, too, contributes to utopics by revealing barriers that have kept us from loving ourselves, living our lives well. He disturbs the barriers, and in so doing, he dares us.

If Ramette at the edges distracts us, look again. By letting entire cities and landscapes encroach upon him, he conjures up single uncompromising moments of precision, only to dream, invent, test, fail, and try again. His insistence on precision is a pursuit for perfect pitch, which Roland Barthes describes in The Neutral as an authenticity in a real relation to others, with oneself and with death, in “desperate vitality.” Christian Bernard, former director of Villa Arson where Ramette studied in the 1980s and kept his studio, puts it well, “Ramettean Man is moral, he knows he is weak and mortal, his is well aware of the common illusions and attempts to correct some of his inborn defects.”

One night, at the Avenue of Stars, a little boy walked past Ramette’s works. He asked his father, “Are these real?” His father said, “Of course not! How can anyone stand like that? They are all digital effects.” This is the kind of parenting one encounters once in a while in the open. This lazy kind of parenting misses one central value of art making - engendering an escapism that Italo Calvino describes as positive and desirable if you were a prisoner who wanted to be free. For the writer, the prison is an amalgam of clichés and received representations. He must plan an escape. Calvino says, “To plan a book – or an escape – the first thing to know is what to exclude.” Ramette excludes the received terms on which life is examined by including a particular slice of rationality, one way of constituting and impregnating the world, that one can have no objection.

The Upside Down World of Philippe Ramette intervenes not just a site, but lives that are averaged out and fenced up in skyward urban spaces. Ramette is not a hero of grandiosities, but our neighbor, sharing with us states of serenity hewn out from the mess. This life, he says, is mine and yours, too. It is embarrassing; it is uncompromising.

To quote Calvino again, “Utopia feels the need for compactness and permanence in opposing the world it rejects, a world that presents an equally refractory front.” Ramette’s works exude compactness and permanence as the “‘absolute rejection’ by means of a world thought out in all its details according to other values and other relationships.” On the opening day, I asked the artist perspiring in a dark blue suit (it was too dark to figure out if it was blue or grey…but it was dark, for sure) what he thinks of utopia. He says, “I like it.”

I can imagine Ramette traveling light, air-borne and all that he is.

Exhibition: The Upside Down World of Philippe Ramette

Date: 28.4. – 29.5.2011

Venue: Avenue of Stars, Tsim Sha Tsui Outdoor exhibition

Website: http://www.frenchmay.com/events/visual-arts

This essay was originally published in the July issue of AM Post.

原文刊於《AM Post》2011年7月