Reviews & Articles

Law Yuk-mui

Yang YEUNG

at 11:12am on 26th January 2016

Captions:

1. 《潤物細無聲》,觀塘碼頭,春天Spring Rain Moistens Things Silently, Kwun Tong Ferry Pier, black and white photograph, 2013

2. 《黃色肖像》The Yellow Portrait, black and white photography, 2014

3. 《垃圾灣、景林邨丶植物》,始於1990, On Junk Bay, King Lam Estate, the Plant, 1990-present, installation

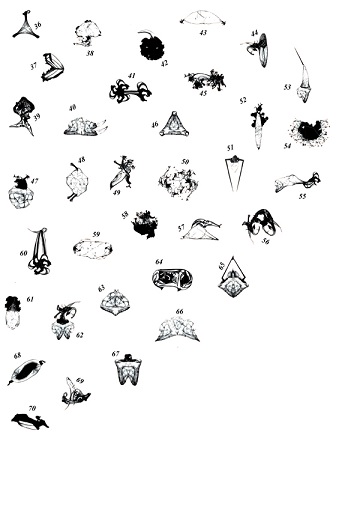

4. 100 ink objects, photo collage with digital output, 2007

5. 《實時報消》 Reality Time Ruining, DVD PAL, 3mins 30 sec

(原文以英文發表,評論羅玉梅的展覽作品。)

At a distance from the works by her fellow artists in the exhibition A Room with a View, where the flood of afternoon sunlight does not reach, stands Law Yuk-mui’s installation, tucked away at a corner.

A small light bulb shines from below, set on top of a glass bottle – one among many of various shapes and sizes, each holding a leaf in shallow water. A video is projected at the corner – a slow moving image of lush green trees, slightly trembling in the wind. The green is particularly prominent in the dimness of the gallery. These two sources of light first draw our attention.

Next to both sides of the video are two cyanotypes in deep blue, pressed with faint and sparsely distributed patterns transposed from petals, twigs, and leaves. Another cyanotype stands alone – Yoko Ono’s Sun Piece (1962). “Watch the sun until it becomes a square,” it says. From this wall, one looks down and looks back at the bottles, and all of a sudden, discovers a shining torch. It casts a blue square onto the lower end of the wall space beneath the cyanotype, almost touching the ground. It is possible to imagine a thread across the gallery that links this light drawing and the Sun Piece, mirroring it.

Woven together in light and shadow, On Junk Bay, King Lam Est., The Plant (1990-present) comes into being. It is worth noting that 1990 was remembered by Law as the year when the reclamation work by landfill was completed and plants moved into Junk Bay (an older name for the district of Tsuen Kwan O). The artist’s love of Junk Bay as her home comes through – it grows as the plants grow from the defilement of garbage, which instills insight rather than ill feelings in the work. To follow the sources of light is to unfold questions about sources of the artist’s life and sources of life itself – its beauty and vitality.

Two more sets of objects are shown alongside On Junk Bay. One of them is Spring Rain Moistens Things Silently, Kwun Tong Ferry Pier (2013) – an unframed black and white photograph of raindrops rippling the sea. In its silence, we hear the rain tapping rhythm. There is also The Yellow Portrait (2014), a mini-installation consisting of a roll of film and a lopsidedly-hung black and white print that originated from a damaged film cartridge, a small cyanotype placed near the ground inscribed with an elongated object (which the artist later told me was a yellow ribbon placed under the sun), and finally, a black and white photograph neatly hung, showing the artist holding an umbrella in the middle of a flat expanse of snow. In the artist statement, Law tells the story of how this photograph came about. She recounts Japanese photographer Eikoh Hosoe’s explanation of his black and white photographic work Ordeal by Roses, in which Mishima Yukio holds a rose between his lips. Hosoe says the rose is yellow rather than white. The yellow, he says, is able to deliver higher contrast than the white. In response, Law made a bet, and then, a photograph. “With my yellow umbrella from Hong Kong, I made a bet with black and white.” She concluded after developing the film that yellow is not brighter than white. Is this a matter for further contestation in science? Is this a matter for further debates in art? I am not as curious about these questions as Law’s “bet”. Yellow is at once the bet itself and the reason for the bet. It is the bet on finding the truth of colors regulated by the nature of black and white film. In the game (though perhaps not entirely in the work), Law liberates yellow from its social contexts, returning it to a visual language and a photographic reality she has long been engaging with as an artist. It becomes yet another source of light in the work, in the sheer energy of its color, showing itself in black and white.

This particular way of living with yellow in relation to the green reminds me of the typographer and poet Robert Bringhurst’s idea of artists owing respect to tangible and intangible objects, like “ideas, voices, sentences, as well as solid objects like screwdrivers and stones, boats and sails, pieces of type and paper.” They include also such “moral ideas” as “the task,” “the art,” “the craft”. Bringhurst explains in Everywhere Being is Dancing that “Morality is a name for a working relationship with objects and ideas, as well as the name of a working relationship with grizzlies, deer, dogs, cats, ravens and red cedar trees and other men and women. But most artists and craftsmen are specialists. This means that their sense of moral obligation is much more highly developed towards some classes of object than toward others.” The point here, as Bringhurst argues, is not that artists and craftsmen are better human beings, but rather, that they are more articulate in this “selective moral sensitivity”. I would further propose that for this sensitivity, they might become vulnerable sometimes for finding themselves exposed to and dependent on all that which is full of potencies to be part of their trade and their being, from the smallest tickle to the most immense – like the depth of snow ever transforming in space and the breadth of seasons ever emerging in time. Not all artists are interested in engaging with and showing this side of their lived worlds. Law, however, actively seeks out for it, without anxiety of failure, without fear of shadows. As a result, her artist-self is humbled.

For some years now, Law’s works have been shown to be conditioned and constituted by that which is not up to her as equally important as the choices she makes. I propose to tentatively call this a certain “outside” (sometimes literally outdoors, exposed to elements of nature’s or human making, but not necessarily). For instance, in an early work 100 ink objects (2007), she dropped ink into a fish tank of water (without the fish), and took random photographs of the way the ink changes shape. Then, having printed the photographs, she chose those conjugations that pleased her. Juxtaposing them against each other, piecing them together, Law pictured a community of diverse marine-biological life. The 100 ink objects eventually came together as an ink-jet print on paper. In this work, her imperative to give meaning to every gesture in the making instrumentalizes her chosen materials to serve art.

Gradually, however, she discovers a different relation with the world. In Time Ruining (2010), Law employs a long take with no camera movement to capture things coming into her lens at the Kwun Tong Ferry Pier. One day, a barge carrying a crane arrived and moved slowly across the frame. Law says in the caption to the three-and-a-half-minute video, “The strength of [the crane’s] movement was as subtle as the pulse rate, demanding a certain kind of attention. Every time I review the shot, I strongly feel that the time was being spent, even though it was only a few minutes.” The making of Time Ruining is conditioned by the “outside” as time in its incommensurable immensity, which gives rise to the beauty of simplicity and poignancy through the artist’s wonder of the unexpected and her patience with accidents. In this light, the recent installation of black, white, yellow, green, and blue could be read as a display of the mutual conditioning of things with time as their material basis – the time for leaves to absorb water, for photosynthesis to complete, for potassium ferricyanide to act…as well as video time, battery time, and, in a curious way, the time for imagination to hold long enough for the sun to become a square.

The Hours by Michael Cunningham begins with August 30th, 1923, an entry from Virginia Woolf’s diary: “I have no time to describe my plans. I should say a good deal about The Hours and my discovery: how I dig out beautiful caves behind my characters: I think that gives exactly what I want; humanity, humour, depth. The idea is that the caves shall connect and each comes to daylight at the present moment.” Interestingly, in Woolf’s original, there is something else after the end of Cunningham's quote – “Dinner!” How the exclamation ended up not being in Cunningham’s novel is not of my concern here. I am interested in how, when one imagines “dinner” coming back to the equation, one takes a breath of relief in between a continuous and serious endeavor. Dinner with an exclamation mark bears the present-at-handness of life itself – the basic stuff it is made of, the time needed for it, the evocation that comes with it… There is also the humor, shared across time. Law’s objects are Woolf’s “characters”. They neither speak nor show, but they are poemed for being “well put together”. To borrow from Bringhurst again, to poem is to make sing or resonate. Law’s solitary ecology of objects does that, too. In the making, the artist’s body must have hopped between them – those kindred spirits of hers – so that she could conceal herself, displace those after-the-fact gestures of art, show this act of concealment, and get lost in the vastness of everything else.

One morning, when a petal of bauhinia came spinning down from the tree, fragments of Law’s body of works came to mind. The petal met my gaze as it reached the height of my shoulder. I felt lucky to have seen the last milli-seconds of its fall. The spinning made me smile. I wonder if Law would, too.

First published in issue 118 (Jan 2016) of a.m.post, Hong Kong.

原文刊於《a.m.post》118期,2016年1月。