Reviews & Articles

Creativity Outside the Art Supermarket

John BATTEN

at 6:32pm on 15th June 2014

Captions:

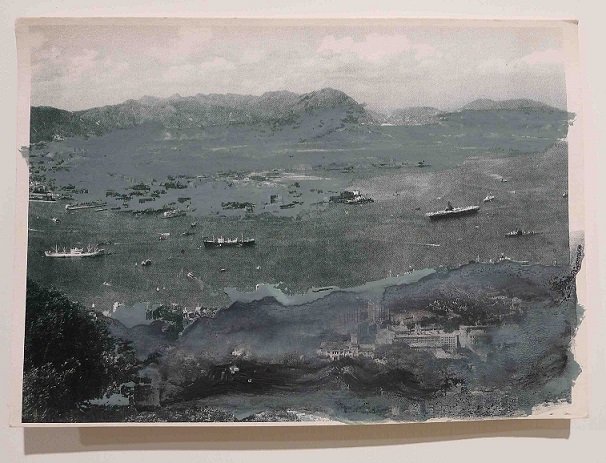

1. Mark Schmitz, Nature release, one of a series of repainted postcards, from West (Becrchtesgaden) to East (Hong Kong), guache on paper, 2014 (exhibited at Goethe-Institut Hong Kong, May 2014).

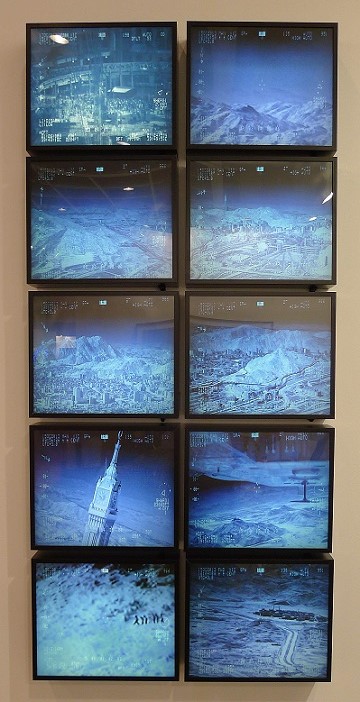

2. Ahmed Mater, Disarm, 2013, from the Desert of Pharan series, 10 LED lightboxes, 31x37cm each, edition of 5. (Courtesy of Athr Gallery, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia)

3. Noel McKenna, Horse on Rural Property, 2014, oil on plywood, 21x44cm.

4. James Capper operating his Hydra Step, 2013, mixed media, dimensions variable. (inside Hannah Barry Gallery's booth at Art Basel Hong Kong 2014)

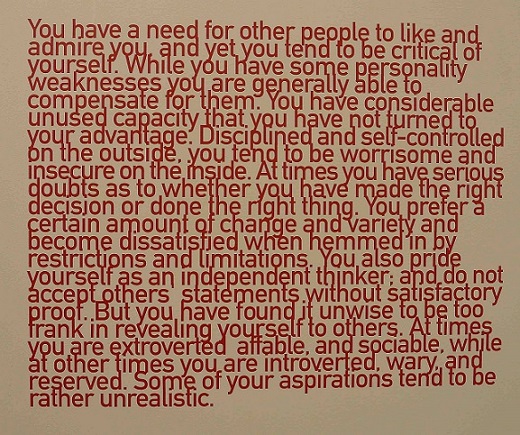

5. Heman Chong, The Forer Effect, 2008, vinyl text on wall, dimensions variable.

All photos: John Batten

(原文以英文發表,題為「藝術超市以外的創意」。)

There is art and then there is the art market. Art relates to artists and their challenges. The art market is about galleries, auctions, sales and money. Art is the visual outcome of ideas and experiments about aesthetics and materials used. The art market is the (eco)system that sells and trades visual art, its pricing and marketing. Art tells visual stories. The art market makes a commodity of visual art objects. Art is the expression of creativity and the art market creates a heightened aura of exclusivity.

The art world’s division of roles between art and the art market is natural, clearly defined and simple: artists deal with creativity and the consequent production of art objects, while art galleries sell artists’ work and deal with the business side of selling art. In essence, despite globalization and ease of communication through the Internet, this is how the art world continues to operate.

At last month’s Hong Kong edition of Art Basel the art market was on full display: a wonderful sprawling supermarket of art and shoppers/collectors measuring the art and themselves. There was overwhelming media coverage; every magazine worthy of its gloss did an ‘art issue’. Stories were built around prominent Hong Kong art personalities, some of dubious pedigree. Hong Kong socialites, clumsily described by a public relations firm in one of their promos as “art influencers”, attended a frenzied round of award presentations, dinners and cocktail functions: fame extended by an art association. And, just in-camera, was the lurking presence of further art market accoutrements: fine cigar companies, the latest luxury car models, discrete private banking client rooms, tourbillon movement watches, and champagne.

It was all wonderfully fabulous!

But the press gave little attention to the many – and higher profile, around the world – international art dealers and curators who flew into Hong Kong. Or, of artists! This is mirrored within the art fair itself. Artists were present at Art Basel, but generally the art market demands artists keep a discrete presence at any art sales event. It is the art market itself, not necessarily artists or even art, which is in the spotlight at a fair. Perceptive art dealers will take limited credit for what the public views. The director of Mother’s Tankstation gallery of Dublin, Ireland sensitively acknowledged to an appreciative visitor of his booth’s showing of artist Noel McKenna’s paintings: “I just did the presentation, the artist did the work.”

British artist James Capper was one of the few who had a continual presence in his dealer Hannah Barry’s booth to operate one of the more unusual exhibits of the entire fair. Capper’s artwork resembles earth-moving machinery, fabricated by him using similar technology and a physical appearance to conventional construction and excavation equipment.

Despite an interest in mechanics and previous work in a vehicle workshop, Capper consciously chose to be an artist. He concluded his interests lay not in designing functional mechanical equipment, but in freedom of expression and creativity. Mechanical design was essentially a conservative discipline serving industry bound by its own culture and boundaries. Art allowed a wider creativity he sought.

Capper’s art pieces are both static and mobile sculptures that the artist operates using a lever-control system, clunky but effective. These pieces were some of the most stimulating art on display at Art Basel. Capper’s work was both familiar and wacky. It looked like functional earth-moving equipment, but it had no obvious use despite being able to move with a walking-like gait. It looked elaborate and practical, but wasn’t. It had some characteristics of an independent automaton, but wasn’t at all. It just looked good and crowds of viewers were entranced to see a machine operating outside the expected, in an art setting.

And for art to succeed, that is what it must - at a minimum - do. Watch out for Capper!

The relationship between artist and some gallery owners can be close. Apart from working together for mutual sustenance, galleries give support and honest comment about artists’ work. A visit to an art fair, with its unequivocal focus on the market, does not reveal the softer, necessary side of the gallery-artist friendship and liaison and its many successful outcomes, including collaborative exhibitions.

Creativity comes from an artist’s space. And, creativity is not obviously promoted at an art fair. But there is much art exhibited that is funky, or tricky, or executed in an undeniably technically brilliant way (for example: hyper-realistic fibreglass figurative sculpture). Such art begs responses seen at a circus side-attraction and their showing intentionally elicits a ‘wow’. Crowds at an art fair love it – it is confirmation of the art world’s art supermarkets. Isn’t it?

A version of this article was published in The Peak magazine, June 2014.