Reviews & Articles

Cracking the Sunflower Seed

John BATTEN

at 1:05pm on 16th July 2011

Captions:

1. Ai Weiwei, Sunflower Seeds, 2010. Mixed-media installation, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and the Tate Modern, London.

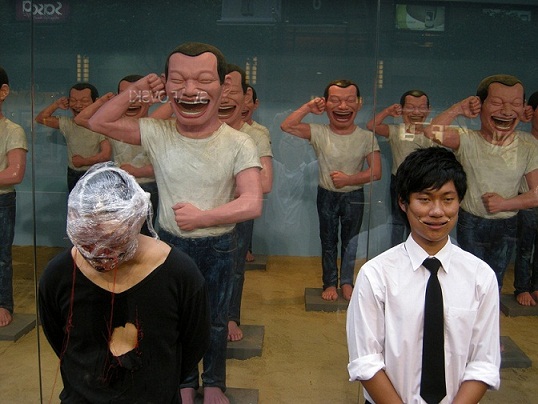

2. Yue Minjun’s Contemporary Terracotta Warriors’ sculpture exhibition at the Times Square, Hong Kong, 2008, and two Hong Kong performers.

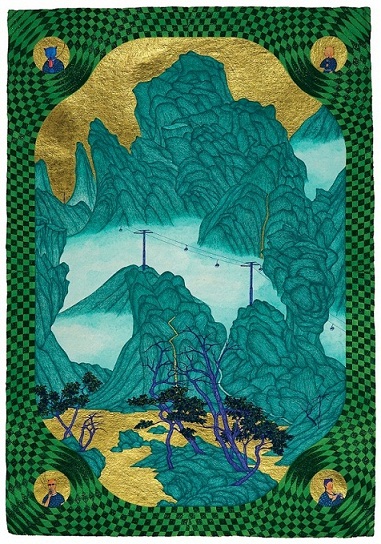

3. Yao Jui-chung. Honeymoon : Mao-kong Gondala, 2010.

4. Laurence Aberhart, Toi Shan.

(原文以英文發表,由艾未未的裝置藝術作品《葵花籽》談起。)

The humble sunflower seed has long been a favourite snack for Chinese people travelling long distances on buses or trains; the tedium of cracking the husk to extract a small seed is compensated by the camaraderie borne of sharing food and travel, and measured, almost, by the mound of empty shells carpeting the floor. Ai Weiwei’s large-scale, hand-made, painted ceramic installation of replicated sunflower seeds covering Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in London recalls a similar scene. His seeds, however, are a metaphor for ideas, similar to those sent using Twitter: a single idea, Ai reminds his compatriots, can mutate virally to form a collection of connected thoughts – consciousness, possibly – to challenge any repressive regime.

Ai is an adept twitterer and publicist and much of his art (including performances and large installation pieces) challenges the illusion of power held by the Chinese Communist Party and mocks its intolerance of enquiry, dissent and censorship. Ai’s public approach contrasts with that of many successful mainland artists who are cautious of attracting unwanted attention. Art auction favourite, Yue Minjun, whose smiley faces have become an unfortunate leitmotiv for mainland Chinese contemporary art, has said:

“My aim is to treat the burdens and suffering in our history in a relaxed and light-hearted way so as to lessen the pressure and powerlessness we feel in real life. In addition, there is an element of standing back from worldly affairs and remaining impassive. In sum, my theme is – ‘pink humour’.” (1)

Ai would probably be dismissive of such thoughts: on hearing that jailed Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo had been awarded this year’s Nobel Peace Prize, he slammed mainland intellectuals who, he said, “should feel ashamed of themselves because many had betrayed the values they once strove for and drifted away from their public responsibilities”. Of course, Ai continued, “it is the regime that should feel most ashamed”. (2) Anger, frustration and cynicism are common on the mainland, where government officials and the rich exert their privileges over everyone else and there is a widening gap between rich and poor, country versus city and those who have urban-residence permits and the many who don’t.

With mainstream mainland painting predominantly decorative and comprising, in an odd juxtaposition, a banal, lurid exoticism, it is through video, short film, performance and photography that artists exhibit a spirited visual debate about the mainland’s culture, society and politics. Lin Yilin’s Safely Maneuvering Across Lin He Road (1995) is an early example of a subtle but critical video about the pace of urban development. Lin, Liang Juhui and Chen Shaoxiong, who together founded the Guangzhou-based Big Tail Elephant Group, for example, escaped the kind of close censorship prevalent in the north. Encouraged by the south’s independently minded Cantonese culture as well as access to Hong Kong’s uncensored cross-border television broadcasts, film and print media, a spirited and critical visual arts community emerged in the south that has enabled the incisive Guangzhou Triennials and Photo Biennials to be unusual official forums of artistic openness.

Chen, commenting on the Cynical Realism painting movement that evolved in the 1980s and has been stylistically dominant on the mainland ever since, said: “That is from the North, it was never done in the South!” (3)

Photography has quietly and efficiently been the most successful media to capture the mainland’s last three decades of momentous change; the pure documentary photojournalism of Vincent Yu depicts anachronistic symbols of workers joining arms with soldiers during the 60th National Day parade in Tiananmen Square and Yang Tiejun captures provincial excess: elaborate small-town and municipal government offices designed in faux White House Georgian style. The work of visiting overseas photographers offers important perspectives of China. Edward Byrtynsky’s large-format Three Gorges Dam Project photographs witness communities uprooted and a landscape changed to build one of the world’s biggest engineering projects. Alternatively, Laurence Aberhart’s 8x10-inch contact prints carefully extol the beauty of the unique hybrid vernacular architecture seen in Macau and Guangdong’s Tai Shan.

Hong Kong and Taiwan have played significant roles in Greater China since Mao’s communist forces took control of the mainland from Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang in 1948, and their projection of a “different” type of China to the world has offered a refreshing, nuanced understanding of what China is and being Chinese means. Hong Kong’s individuality and dogged protection of freedom of expression and the rule of law and Taiwan’s continuing determination for independence are tempering influences: their contemporary art is similarly independent, with the mainland having little ostensible influence. Hong Kong and Taiwan are what Ai Weiwei might, on a good day, refer to as blooming sunflowers. The mainland, however, is a tougher seed to crack; but, inevitably, as Ai would argue, it will crack. (4)

Notes:

(1) Yue Minjun, quoted from ‘Contemporary Terracotta Warriors’ sculpture exhibition wall text, Times Square, Hong Kong, 2008.

(2) Quoted text in ‘Proud or shamed: intellectuals react to Nobel win’, in South China Morning Post, 10 October 2010.

(3) Interview in documentary film, From Jean-Paul Sartre to Teresa Teng: Contemporary Cantonese Art in the 1980s, Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong, 2009.

(4) At the time of writing, Ai Weiwei was himself placed under house arrest by mainland authorities for threatening to organise a protest dinner against the demolition of his Shanghai studio. The dinner was to serve 10,000 river crabs that, if pronounced, sound like "harmonise", the euphemism used by mainland authorities for censorship.

Originally published in Asia Literary Review, Volume 18, Winter, 2010.

1. Ai Weiwei, Sunflower Seeds, 2010. Mixed-media installation, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and the Tate Modern, London.

2. Yue Minjun’s Contemporary Terracotta Warriors’ sculpture exhibition at the Times Square, Hong Kong, 2008, and two Hong Kong performers.

3. Yao Jui-chung. Honeymoon : Mao-kong Gondala, 2010.

4. Laurence Aberhart, Toi Shan.

(原文以英文發表,由艾未未的裝置藝術作品《葵花籽》談起。)

The humble sunflower seed has long been a favourite snack for Chinese people travelling long distances on buses or trains; the tedium of cracking the husk to extract a small seed is compensated by the camaraderie borne of sharing food and travel, and measured, almost, by the mound of empty shells carpeting the floor. Ai Weiwei’s large-scale, hand-made, painted ceramic installation of replicated sunflower seeds covering Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in London recalls a similar scene. His seeds, however, are a metaphor for ideas, similar to those sent using Twitter: a single idea, Ai reminds his compatriots, can mutate virally to form a collection of connected thoughts – consciousness, possibly – to challenge any repressive regime.

Ai is an adept twitterer and publicist and much of his art (including performances and large installation pieces) challenges the illusion of power held by the Chinese Communist Party and mocks its intolerance of enquiry, dissent and censorship. Ai’s public approach contrasts with that of many successful mainland artists who are cautious of attracting unwanted attention. Art auction favourite, Yue Minjun, whose smiley faces have become an unfortunate leitmotiv for mainland Chinese contemporary art, has said:

“My aim is to treat the burdens and suffering in our history in a relaxed and light-hearted way so as to lessen the pressure and powerlessness we feel in real life. In addition, there is an element of standing back from worldly affairs and remaining impassive. In sum, my theme is – ‘pink humour’.” (1)

Ai would probably be dismissive of such thoughts: on hearing that jailed Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo had been awarded this year’s Nobel Peace Prize, he slammed mainland intellectuals who, he said, “should feel ashamed of themselves because many had betrayed the values they once strove for and drifted away from their public responsibilities”. Of course, Ai continued, “it is the regime that should feel most ashamed”. (2) Anger, frustration and cynicism are common on the mainland, where government officials and the rich exert their privileges over everyone else and there is a widening gap between rich and poor, country versus city and those who have urban-residence permits and the many who don’t.

With mainstream mainland painting predominantly decorative and comprising, in an odd juxtaposition, a banal, lurid exoticism, it is through video, short film, performance and photography that artists exhibit a spirited visual debate about the mainland’s culture, society and politics. Lin Yilin’s Safely Maneuvering Across Lin He Road (1995) is an early example of a subtle but critical video about the pace of urban development. Lin, Liang Juhui and Chen Shaoxiong, who together founded the Guangzhou-based Big Tail Elephant Group, for example, escaped the kind of close censorship prevalent in the north. Encouraged by the south’s independently minded Cantonese culture as well as access to Hong Kong’s uncensored cross-border television broadcasts, film and print media, a spirited and critical visual arts community emerged in the south that has enabled the incisive Guangzhou Triennials and Photo Biennials to be unusual official forums of artistic openness.

Chen, commenting on the Cynical Realism painting movement that evolved in the 1980s and has been stylistically dominant on the mainland ever since, said: “That is from the North, it was never done in the South!” (3)

Photography has quietly and efficiently been the most successful media to capture the mainland’s last three decades of momentous change; the pure documentary photojournalism of Vincent Yu depicts anachronistic symbols of workers joining arms with soldiers during the 60th National Day parade in Tiananmen Square and Yang Tiejun captures provincial excess: elaborate small-town and municipal government offices designed in faux White House Georgian style. The work of visiting overseas photographers offers important perspectives of China. Edward Byrtynsky’s large-format Three Gorges Dam Project photographs witness communities uprooted and a landscape changed to build one of the world’s biggest engineering projects. Alternatively, Laurence Aberhart’s 8x10-inch contact prints carefully extol the beauty of the unique hybrid vernacular architecture seen in Macau and Guangdong’s Tai Shan.

Hong Kong and Taiwan have played significant roles in Greater China since Mao’s communist forces took control of the mainland from Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang in 1948, and their projection of a “different” type of China to the world has offered a refreshing, nuanced understanding of what China is and being Chinese means. Hong Kong’s individuality and dogged protection of freedom of expression and the rule of law and Taiwan’s continuing determination for independence are tempering influences: their contemporary art is similarly independent, with the mainland having little ostensible influence. Hong Kong and Taiwan are what Ai Weiwei might, on a good day, refer to as blooming sunflowers. The mainland, however, is a tougher seed to crack; but, inevitably, as Ai would argue, it will crack. (4)

Notes:

(1) Yue Minjun, quoted from ‘Contemporary Terracotta Warriors’ sculpture exhibition wall text, Times Square, Hong Kong, 2008.

(2) Quoted text in ‘Proud or shamed: intellectuals react to Nobel win’, in South China Morning Post, 10 October 2010.

(3) Interview in documentary film, From Jean-Paul Sartre to Teresa Teng: Contemporary Cantonese Art in the 1980s, Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong, 2009.

(4) At the time of writing, Ai Weiwei was himself placed under house arrest by mainland authorities for threatening to organise a protest dinner against the demolition of his Shanghai studio. The dinner was to serve 10,000 river crabs that, if pronounced, sound like "harmonise", the euphemism used by mainland authorities for censorship.

Originally published in Asia Literary Review, Volume 18, Winter, 2010.