Reviews & Articles

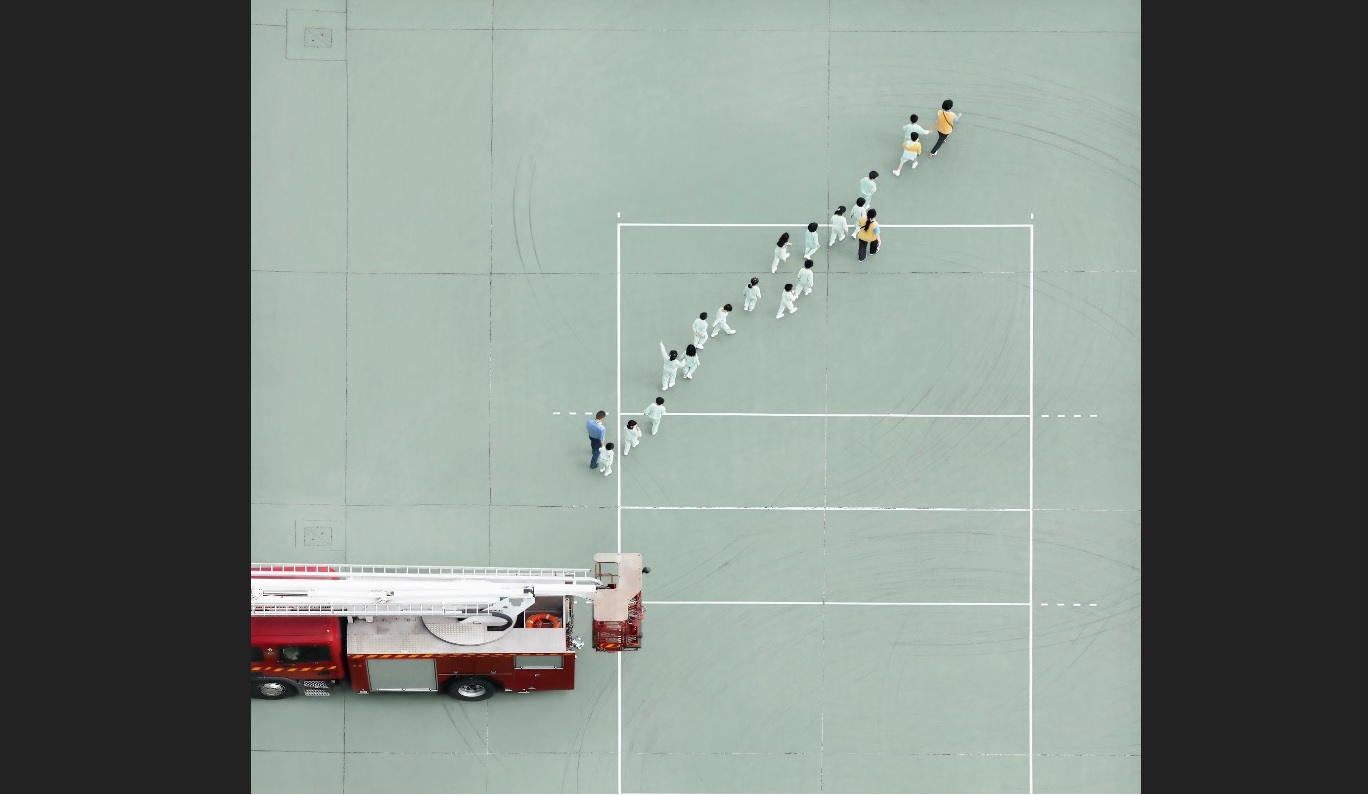

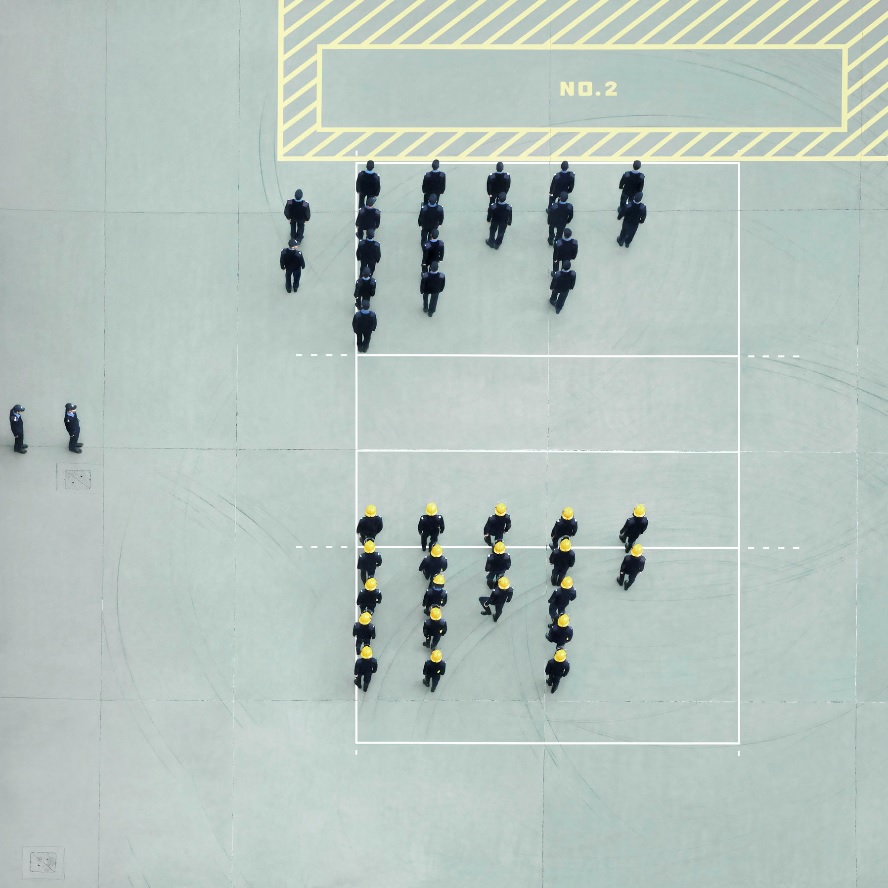

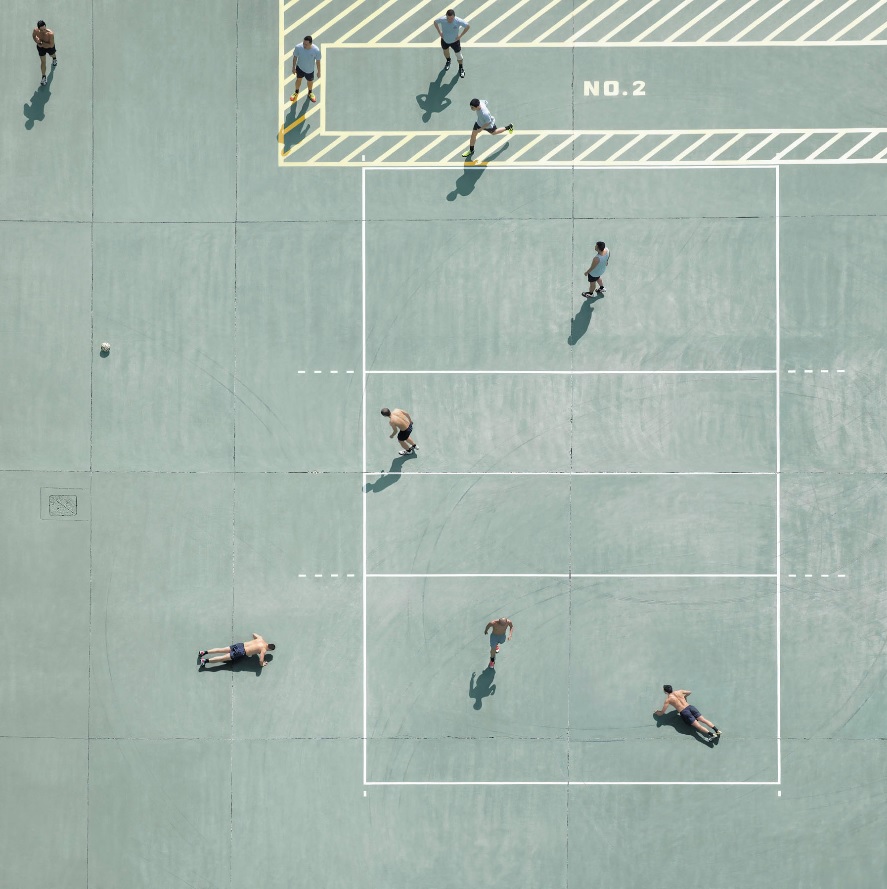

Chan Dick: Chai Wan Fire Station

Yang YEUNG

at 12:08pm on 22nd May 2018

Captions:

1. – 5. Chan Dick, Chai Wan Fire Station 柴灣消防局

All photos courtesy of the artist and Novalis Gallery.

(原文以英文發表,評論「柴灣消防局: 陳的個展」。)

Nestled in tranquility and tenderness, Chan Dick’s Chai Wan Fire Station offers a glimpse into the lesser-known life of firefighters. Non-fiction but not documentary in style, the images prompt memories, stories, and feelings. At no single moment is anyone self-conscious of the beauty they are a part of. Shoulder-to-shoulder while individuated, the male bodies give birth to moments of magnanimity.

The organic rhythm shaping the images reminds me of The Forgotten Space by artist Alan Sekula reflecting on the amnesia in America regarding its relation to the sea. “The sea is all about slow time – things move slowly, there's a lot of waiting – and as such it contradicts all the mythologies of instantaneity perpetuated by electronic media." The sea is not the subject of Chai Wan Fire Station, but it is geographically close by. It is not difficult to imagine the skin of the firefighters brushed by an occasional breeze as their shadows lengthen in the sun, and as they attend to the rise and fall of water from a relaxed fire hose. The sensuousness of slow-moving male bodies is in sharp contrast to the more dominant representations in mass visual culture where male bodies are masked in business attire, charged with righteousness, as if always on top and in control. Instead, Chan has produced in and for Chai Wan Fire Station a different sensibility.

The artist’s grammar of creation [2] however, goes beyond the realm of meaning already established in social life. At first sight, the lines and grids could be deceptive for dividing up and quantifying space. A closer look reveals Chan’s perception of space as infinite: instead of setting up boundaries that exclude the outside from the inside, the lines and grids are imbued with the capacity to stretch away from the tentative gravitational center of in each frame, dispersing and rippling it outward to a world that is open. Anthropologist Tim Ingold, in Being Alive, speaks of the “open world” as having no boundaries of exclusion, “no insides or outsides, only comings and goings. Such productive movements may generate formations, swellings, growths, protuberances and occurrences, but not objects.” [3] It is in this configuration of openness that a sense of proportion is conjured.

How has it been possible for Chan to connect with this understated beauty? Many times Chan had spoken of waiting as a vital part of creating Chai Wan Fire Station, and more specifically, waiting from the 14th floor of his old studio, looking through a small shaft window. Something might or might not happen. For the artist, the waiting is a calling from instinct, which unfastens him from the single-mindedly directed will. Waiting helps him to suspend and transform the old habits of staging a scene, externalizing all that has been constructed in his mind, scripting a narrative to be actualized, and a sense of urgency towards completing a job, as if a “short-distance runner”, as Chan would call himself. Chai Wan Fire Station changes his priorities in perhaps an unconscious but definite way. He imposes limits upon his trained consciousness (as a different kind of photographer) to seek another kind of freedom. In letting chance encounters direct his practice, Chan is far from reacting to the impulse to hunt for images on the street, which he has stopped doing. He is looking for something more enduring, subtle, and able to move himself in more profound ways – some human condition yet to be named. Chan speaks in humility of himself as a beginner in practicing art independently, with the question of what ought to bind his life, his practice, and the world nudging him forward. The artist’s response to the calling unplanned for does a lot for viewers, too. His wait lifts the hold of their memory of the subject-matter. The images lead viewers into the artist’s mode of inhabiting time as it unfolds in the next and every moment, in uncertainty and hope.

In touching the beautiful as fragile and subject to imminent change (by a fire alarm, for instance, that might suddenly sound out), every image becomes precious. It holds up a kind of equanimity that is fair. Fairness, says Elaine Scarry, is when beauty pushes us to concerning ourselves with justice, as in the idea of a fair playing field. [4] I imagine Chai Wan Fire Station as a circle of particular lives that care to be fair to the unquestionable value of all lives.

Equanimity in place requires equanimity within to discern. Here lies an artist’s distinct sensitivity that could become everyone’s, if willing.

Notes

[1] Grammars of Creation is the title of a book by George Steiner published in 2002.

[2] Tim Ingold. Being Alive, Essays on movement, knowledge and description, Oxon: Routledge, 2011.

[3] Elaine Scarry’s lecture “The Beauty of the World and the Nuclear Peril”, Uppsala University, Jan 25, 2018. See also her book On Beauty and Being Just, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001.

First published in May 2018 by Novalis Art Design Gallery on the occasion of Chai Wan Fire Station: A solo exhibition by Chan Dick