Art Issues

- BiennialsThe latest article on a special issue topic is below. Other articles on the same topic can be read by clicking on the 'Archive' year and month on the side-bar.

你我未來 循環再造 (Recycling Our Future)

John BATTEN

at 5:55pm on 26th February 2016

Captions:

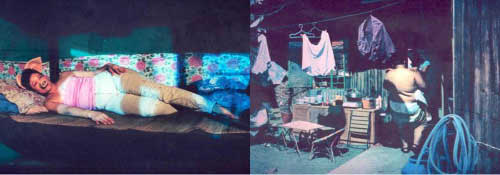

1. Still from Fruit Chan's movie Hollywood Hong Kong, 2000.

2. Dennis Maher, Hole in the (Window of the) World House, mixed media, 2015. An installation at 2015 UABB, Shekou, Shenzhen. Photo courtesy: John Batten.

3. Rob Voerman, Shenzhen Entropy, mixed media, 2015. An installation at 2015 UABB, Shekou, Shenzhen. Photo courtesy: John Batten.

(Please scroll down for English version.)

正當北京又再呼吸著難以忍受的毒氣,氣候會議剛於巴黎圓滿舉行,兩年一度的深港「城市\建築」雙城雙年展也告開展,現正在深圳蛇口舉行。展覽上有一系列來自世界各地的參展作品,以獨特的角度審視城市環境。雙年展的焦點是我們的城市和市內的建築及城市規劃設計。大型市區的設計落在建築師與規劃師的手裡,而城市所面對的問題,都在雙年展中得到詳盡闡述。然而,說到解決方案––真正可行的解決方案––在展品中卻難以找到!

誠然,雙年展所涵蓋的議題有不少在巴黎會議中也有討論。我們的環境需要我們悉心照料、修補,也需要以新的方針建造城市。Aaron Betsky是雙年展四位策展人之一,他表示:「本屆雙年展有一個很簡單的論點:我們已經有足夠的東西了。我們有足夠的建築物、足夠的物件和足夠的影像。」這似乎帶著理想主義。他續指建築需要令建築物和資源得到重用和再生。Betsky建議我們未來的城市,應該是一幅重用物件的「拼貼畫」,物件在裡面都被賦予其他用途。

很可惜,對於如何在資本主義的消費與增長需要,以及更佳的資源管理和環境保育之間達致正確平衡,雙年展並沒有給我們滿意的解釋。這正是發展中國家在巴黎向其他發達國家所解釋的兩難局面––那些早已經歷結構進步的國度,自然較容易放慢發展腳步,藉以減少資源浪費和碳排放。只是同一舉措對於正嘗試提高生活質素的國家而言卻不大可能。

香港是人煙密生活的典型,市內的高密度人口,讓我們可以享有一套高效的鐵路系統,而它的運作還有利可圖。大都會生活其中一件最可悲的事情,就是永無休止的交通擠塞和由此而來的空氣污染。這是一個對立:應該享受汽車代步的自由和個性,還是善用大眾運輸工具以換來更佳的公共利益?如果可持續發展是一個真正的目標,這種對立便是每一個城市都面對的兩難。透過逐步推行生活習慣的小改變來減少對氣候轉變的影響是可能的。香港的膠袋稅正是以正面解決方案減少廢物的小小一例。現在,我們也應該跟隨三藩市,禁止出售以膠瓶包裝的水——消費者可改以帶同自己的水瓶,前往商店和港鐵站內的添水站添水。在高樓大廈加裝太陽能發電板又如何?當發電板不只是為自己的大廈供電時,所得電力可以售回電網——這種模式正在澳洲實行,而且已大大減少了燃煤發電廠的產電量,換言之也大幅降低了排放。

雙年展的策展人均主張建築物不應輕易拆毀,並指出它們應該與其他物料一樣被回收再用。清拆重建一直以來都是香港都市更新的首選方式,原因是盡量提高可用空域。然而,到了未來,我們有需要在大城市推行考慮環境的措施,到時候我們便會採用更新穎、更嚴厲的規劃方法。平衡各方、以人為本的規劃策略,可以帶來以社區為重的重建方針。以大廈改建成高層建築後的利潤來資助保留較低矮的建築物,可以令社區受惠。這種模式已在香港出現:基於防火安全理由,校舍總是採取低層設計,在擠迫的鬧市中,校舍所在的地點,正好為社區保持了通風的走廊。部份政府物業也擔當類似角色,雖然幾乎都不是故意的。以中西區關注組爭取保留的元創坊和前中區政府合署為例,保留了兩個建築群,令附近一帶得以保住眺望維多利亞港的視野,更讓鄰近的擠迫半山區得到較好的通風和採光。

中環填海區至今仍只是一片工地:它應該是一個大型公園,但中環至灣仔繞道把 它一分為二,而公園的建造似乎被刻意推遲––據說是等待所有繞道建築工程完成。 現有郵政總局和天星碼頭停車場這兩個重要的現代主義風格例子,均清拆在即,它們的土地會出售用來發展商廈。在未來數年,隨著中環的整體高度不可避免地提高,這兩座建築物將可作為區內重要的通風廊。它們不應該被保留和重用嗎?

如何建立未來的潔淨、可持續和讓人安居樂業的大城市,深圳雙年展只提供了很少答案。但雙年展中兩名視覺藝術參展人Rob Voerman(荷蘭,如圖)和Dennis Maher (美國)則以檢來的物料建造了兩座精緻的建築物,讓我想起位於鑽石山的香港最後一個大型寮屋區(現身於在陳果的電影《香港有個荷里活》中)。這些建築物是支持未來循環再用的一大挑戰,但它們所預視的世界,其命運是有更多人將住在這些不正規而且設備不足的居所內。

瀏覽更多資料:

深港「城市\建築」雙城雙年展

Dennis Maher

Rob Voerman

原文刊於《明報周刊》,2016年1月2日。

Recycling Our Future

by John Batten

While Beijing was again breathing unbearably poisonous air, the recent Paris climate change conference coincided with the opening of the Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture currently running in Shekou, Shenzhen. The Biennial has a range of exhibits from around the world and uniquely considers the urban environment. It focuses on the architectural and urban planning design of our cities and the buildings within them. The design of large urban areas is in the hands of architects and planners, and the problems facing cities are well described in the biennial – but solutions – real, achievable solutions - are harder to find amongst the exhibits!

Inevitably, the biennial covers similar issues discussed in the Paris conference. Our environment urgently needs care, repair and new approaches to building cities. Aaron Betsky, one of the biennale’s four curators, says that “This Biennale makes a simple argument: we have enough stuff. We have enough buildings, enough objects, and enough images.” This appears idealistic, and he further argues that architecture needs to reuse and recycle buildings and resources. Betsky suggests that our future cities will be a “collage” of reused objects that have been readapted for other uses.

The biennial unfortunately does not satisfactorily explain how we get the correct balance of capitalism’s need for consumption and economic growth alongside the need for better resource management and environmental conservation. This is the exact dilemma that developing nations explained in Paris to the world’s developed countries – those nations that had already undergone structural advances could more easily make cutbacks to their development to reduce resource waste and carbon dioxide emissions. This is not so possible for countries trying to raise their standard of living.

Hong Kong is a model for high-density living. The city’s high-density population enables an efficient and profitable MTR railway system to function. One of the greatest miseries of big city living is endless traffic jams and associated air pollution. It is the freedom of car travel and individuality versus the better good of mass transportation: it is a dilemma each city faces if sustainability is to be a real goal. The implementation of small incremental behavioral changes to reduce the impact of climate change is possible. Hong Kong’s plastic bag levy is a small example of a positive solution to a reduction in waste. Now, we should also follow San Francisco’s banning of the sale of water in plastic bottles – bringing instead our own flask to innovative re-filling stations installed in shops and MTR stations. And, what about solar panels being incorporated into the framework of high-rise buildings, and when not producing electricity for its own building can be sold back into the electricity grid – as now happens in Australia and which has considerably cut the output of coal-fired power stations, thus substantially cutting emissions.

The biennial curators advocate buildings should not easily be demolished, but, like other materials, be recycled. Demolition and rebuilding has long been the preferred redevelopment option in Hong Kong, ostensibly to maximize a site’s available air space. However, in the future, the necessity to impose environmental considerations in our large cities will see the imposition of newer, drastic approaches to planning. A balanced, people-first planning strategy could see a community approach to redevelopment. Entire communities could benefit in the sharing of profits of large high-rises to cross-subsidise the retention of selected low-rise buildings. Hong Kong sees this already: schools are low-rise for fire safety reasons, but their location also ensures air corridors in crowded districts. Some government properties play similar, almost unintentional, roles: for example, both PMQ and the former Central Government Offices, were sites that the Central & Western Concern Group campaigned to preserve – these two sites continue to allow sightlines towards Victoria Harbour, and good airflow and light for neighbouring properties in crowded Mid-levels.

The Central Reclamation is still a building site: it should be a large park, but the Central to Wan Chai by-pass road cuts it into two and construction of the park appears to be intentionally delayed – supposedly waiting for all the by-pass construction work to be completed. Slated for demolition and land sale for high-rise development is the current General Post Office and the important modernist-style ‘Star’ Ferry Carpark. In years to come as Central grows inevitably higher, these two buildings could be valuable as low-rise breathing corridors. Shouldn’t they be retained and reused?

The Shenzhen biennial gave few answers to how we build future clean, sustainable and enjoyable-to-live-in large cities. But two exhibiting visual artists at the biennial, Rob Voerman (Holland) and Dennis Maher (USA) built two intricate buildings from found material. They reminded me of the houses in Hong Kong’s last large-scale squatter area in Diamond Hill (epitomized in Fruit Chan’s movie, Hollywood Hong Kong). These buildings are a challenge in support of a recycling future, but also anticipate a world whose fate may see many more people living in such informal and inadequate accommodation.

Links for further information:

Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture

Dennis Maher

Rob Voerman

Originally published in Ming Pao Weekly, 2 January 2016.