藝評

拿捏不錯的平衡 | A fairly good balance

約翰百德 (John BATTEN)

at 10:56am on 25th April 2020

圖片說明:

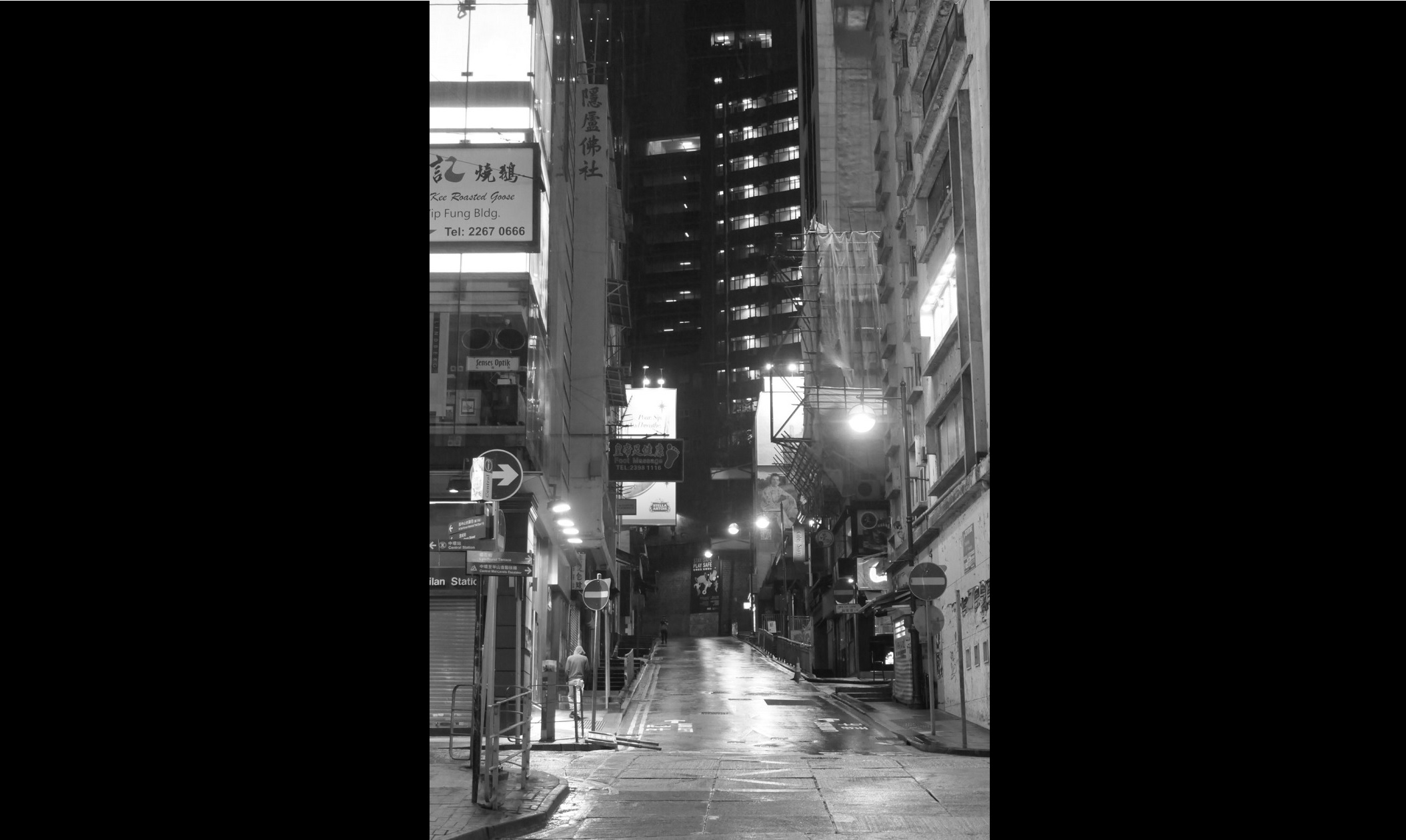

2020年4月5日星期日,是香港七人欖球賽原定舉行的最後一天,蘭桂坊本來會水洩不通。今年,中環的街道因為限聚令和多項公眾活動取消變得杳無人煙。攝於2020年4月5日晚上10時30分,香港中環德忌笠街。圖片: 約翰百德

Caption:

Sunday, 5 April 2020 would have been the end of the scheduled Hong Kong Rugby 7''s weekend, and Lan Kwai Fong would have been heaving with thousands of people. This year, Central streets were deserted due to the imposition of social isolation measures and cancellation of public events. Circa 10.30pm, d''Aguilar Street, Central, Hong Kong, 5 April 2020. Photo: John Batten

(Please scroll down for English version)

在墨爾本機場登上回港國泰航班時,一切都似乎能夠如期進行。然後,機長宣佈機翼發生了輕微機件故障,需要技術人員檢查。檢查過後,機長宣佈航班製造商空中巴士(Airbus),需要就應否更換某零件作最後決定。原定兩小時的等待變成四小時,我們就這樣錯過了在2020年3月18日午夜12點正前抵港的機會,需要接受剛實施的14天強制檢疫。機長就延誤致歉,並宣佈不希望抵港後展開家居隔離的乘客(這時航空公司已改稱我們為「客戶」),可以選擇下機。約有20名乘客下了機,我和其餘乘客則坦然、冷靜地接受了這個消息––遲到就是遲到,而且,能夠安全到埗我已很高興。我吃過晚餐,看了《樹大招風》(2016)這部講述老香港賊王的電影。空服人員告訴我們已完成了維修的「文件」,半小時內便可起飛。正要起航時,一名女孩突然感到不適,全家人也得下機和取回行李。然後,一名全身穿上保護衣的機組人員現身,為這家人的座位消毒,再倉促、不怎有效率地把幾張毛毯「封起」座位,不讓其他乘客使用。事件再次提醒機艙內戴著口罩的乘客,2019新型冠狀病毒終於傳遍了整個世界。

我們的CX 104較原定時間遲了6小時,降落時已是零晨3時30分,成為規定海外抵港人士必須家居檢疫實施後首班到港航班。我們被帶往排隊的地方,獲發一份需要我們簽署的正式檢疫令,還有一封指引,包括一份用來紀錄每天量體溫兩次的表格,也列出了多個方格選項,讓我們回答有沒有感到「頭痛」、「腹瀉」、「發燒」等新冠肺炎已知病徵。排隊時,我們被戴上一條追踪二維碼手帶。我解釋說我沒有智能電話,所以無從下載應用程式。一名官員告訴我說:「不用擔心,我們明天會打電話給你,再送一部過來」。接下來的兩星期,我收到幾次有關手帶的電話,但和很多其他人一樣,追踪功能從來沒有啟動過。

隔離期間,我的日常就是準備素食食物、閱讀、為很多擱下已久的工作趕進度、睡覺和做運動。我一切從簡,也沒有經常追看新聞。我知道,和去年香港連場示威一樣,不斷追看新聞只會令憂慮加劇。如我所料,首星期隔離的時間過得很慢,但第二周很快便過去了。在可以外出的首幾天,我很清楚知道自己的家一直擔任安全泡泡,為我提供保護,減低了染上病毒的可能。現在走到外面的廣闊世界,我將會不斷有機會和不認識的人接觸,病毒也可以存在於我碰到的所有表面,有可能傳給我。這其實是過份緊張的看法,因為只要做好防疫措施,保持社交距離、避免人多的地方、勤洗手、戴口罩和拒絕觸摸臉部已經非常足夠。這些措施需要自律,而走在香港的街上,看到人人都嚴守這些簡單的防疫行為,我感到非常欣慰。

政府官員很多時候會過份執著行政流程,而未有聚焦於實際情況。要就新冠肺炎病毒和香港流行病學建立一般知識,病毒檢測是一大關鍵。我以為自己在進入香港和在檢疫兩星期時應該接受測試。我以為接到電話時,問是不是有關手帶,而是更多關於我的健康狀況、我之前從哪國回來等,而且在居家隔離的中段時間也應該接受新冠病毒測試。越多人檢測,便越能加深我們對病毒的瞭解,越清楚它在香港的傳播情況。

幾乎每一天都有具有影響力人士進言,表達他們對進一步隔離、政府下一步應考慮哪些措施的想法。有建制派人士希望延遲9月的立法會選舉(我可以冷嘲熱諷地說「當然他們會這樣說!」);也有其他人建議像意大利一樣鎖國封城,又或強制執行所有人在公眾地方均應戴口罩。令人意想不到的,是本港衛生官員在平衡各方而言似乎拿捏得不錯,既保持了一定個人自由,讓市民可以在必要時流動,也實施了有一定成效的抗疫措施。

每個國家、每個城市都不一樣。香港本身有很多劏房,公屋和私樓也很䄂珍,還有極不人道的籠屋。大家都明白,我們平時的生活空間已經非常狹窄,在香港實施封城將會成為大災難。香港和西方國家不同,大部份住屋都沒有後園或太多私人空間––每家人和鄰居之間非常靠近,而且因為居住環境擠迫,很多人根本不會在家煮,也不會在家吃飯。

看看公共屋邨的休憩空間,便不難發現人們已找到居家以外安全地自我隔離的戶外空間!

原文刊於《明報周刊》,2020年4月9日

A fairly good balance

by John Batten

All looked on schedule as we boarded our Cathay Pacific flight at Melbourne airport. Then, the aircraft captain announced there was a small mechanical problem in the plane’s wing requiring technicians to check. They checked, and the captain then announced that Airbus, the airline’s manufacturer, would need to make the final decision on whether to replace a part. A two hour wait became four hours, and the opportunity to arrive in Hong Kong before 12midnight on 18 March 2020, before a compulsory 14-day quarantine was imposed, was missed. The captain apologized for the delay and announced that passengers (or “customers” as airlines now refer to us) could disembark if they did not wish to be home-quarantined on their arrival in Hong Kong. About 20 passengers disembarked. I and the other passengers took the news stoically and calmly – there was little to be done about being late, and besides, I am just happy to arrive safely. Dinner was served and I watched Trivisa (2016), a good old-style Hong Kong gangster movie. It was then announced that the “paperwork” for the repair had been completed and we would get clearance to fly in the next half-hour. Then, when we were set to depart, a passenger’s daughter felt sick, the family disembarked, their luggage removed. One of the cabin crew appeared in full PPE (personal protection equipment) disinfecting the family’s row of seats; disconcertingly (it didn’t seem very effective) a couple of blankets were placed over those seats to ‘seal’ them off from other passengers. It was another reminder, as was our plane full of face-masked passengers, how Covid-19 had finally travelled around the world.

Our flight, CX 104, arrived in Hong Kong six hours late, at about 3.30am; we were the first flight to arrive in Hong Kong under the new home-quarantine regulations for overseas arrivals. We were led to a queue and given an official quarantine order to sign, an envelope of instructions, including a daily table to complete our body temperature twice a day and boxes to tick if we experienced “headache”, “diarrhea”, “fever” etc. – any of the known symptoms of Covid-19. In the queue, we then had a tracking Q-code bracelet placed on our wrist. I explained I did not have a smartphone to download the app. “No worries”, I was told by an official, “we will ring you tomorrow and a smartphone will be delivered to you.” I got a couple of phone calls about the bracelet over the next two weeks, but – like many others – the tracking feature was never activated.

My quarantine was a daily routine of (vegetarian) food preparation, reading, catching-up on many long-neglected tasks, sleeping, and exercise. I kept it all simple and didn’t constantly check news reports. I knew, similar to last year’s Hong Kong protests, that obsessive news monitoring only increases anxiety. As I suspected, my first week in quarantine went very slowly, but the second week went very fast. On my first days outside again, I was conscious that the safe bubble of my own home protected me from the possibility of catching the virus and that now venturing into the larger world was a constant opportunity for unknown people and surfaces that I touched to hold the virus and for it to be passed to me. But, that’s a paranoid view: social distancing, avoiding crowded places, hand washing, wearing a face-mask and resisting touching our face are excellent preventative measures. That requires self-discipline and I was pleasantly surprised when I walked the streets that Hong Kong was overwhelmingly adhering to these simple rules of preventative behaviour.

Officials can be unnecessarily fussy about administrative process rather than the substance of an issue. One of the crucial aspects in building our general knowledge of Covid-19 and Hong Kong’s particular epidemiology is to do testing for Covid-19. I believe I should have been tested for the virus as I entered Hong Kong, and also during the two weeks of my quarantine. I should have been rung, not to be asked about my bracelet, but rigorously questioned about my health and where I had travelled from; and mid-quarantine, been given a test to check for Covid-19. The more we test, the more we know about the virus and its spread throughout Hong Kong.

Almost daily, someone of influence has an opinion about what levels of further isolation and measures the government should consider next. Some members of the pro-government camp, and I could cynically say ‘of course, they do!’, wish to postpone the September Legislative Council elections. Others suggest we introduce a lock-down like in Italy, or, make wearing facemasks compulsory. Amazingly, Hong Kong’s health officials have achieved a fairly good balance between maintaining personal freedoms, allowing necessary movement of people, and imposing an effective level of preventative measures against the spread of Covid-19.

Every country, every city is different. Hong Kong, with its many sub-divided flats, small public and private housing units and inhuman cage-homes is, as we know, a tight place in which to live. A lock-down in Hong Kong would be a disaster. Unlike western countries, the majority of Hong Kong housing doesn’t have backyards or much private space – families and neighbours live closely together and many people don’t even cook or eat at home, as it is so crowded. Just look at the recreation areas surrounding public estates: people find outdoor space to safely isolate themselves outside their homes!

This article was originally published in Ming Pao Weekly on 9 April 2020. Translated into Chinese by Aulina Chan.