藝評

South Ho''s Force Majeure and Ching Chin Wai''s Liquefied Sunshine — A Review

楊陽 (Yang YEUNG)

at 9:42am on 25th November 2019

Captions:

1. Luke Ching Chin Wai About Dark Night, White Cloud 2013 Archival inkjet print

2. Luke Ching Chin Wai, About Dark Night, White cloud, 2013, Archival inkjet print

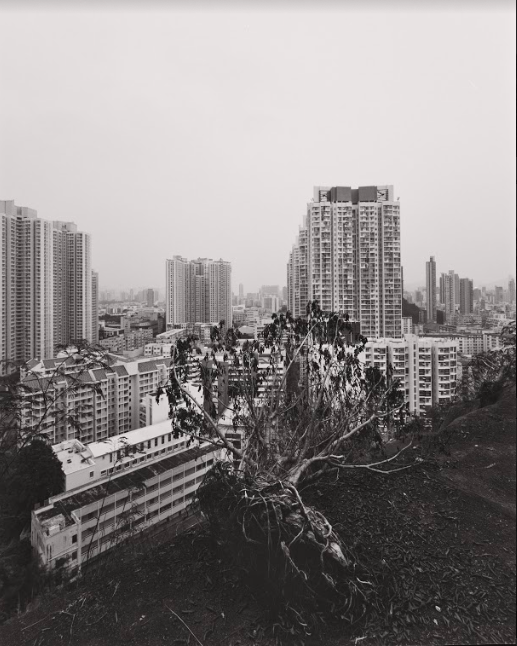

3. South Ho Siu Nam, Whiteness of Trees IV, 2018, Archival inkjet print

4. South Ho Siu Nam, Whiteness of Trees VIII, 2018, Archival inkjet print

Image courtesy of the artists and Blindspot Gallery.

(原文以英文發表,評論〈程展緯:液化陽光 | 何兆南:不可抗力〉展覽。)

At a distance, a piece of wood standing in the middle of the gallery appeals to the eye: singular, tall, and mastering the space. A closer look reveals the piece of wood to be as thin as a plank. Having been slashed at the front and back, the unnaturalness of the two exceedingly flat surfaces is laid bare. Named Mr. One-Third (2019) by the artist, the sculpture is made with pieces of a paperbark tree fallen to make way for a highway in Shatin earlier this year. The material that Ho works with has been violently wounded by this society’s systematic and large-scale disposal of everything rendered useless and in the way of speed and efficiency. In an interview, Ho expressed to me how he was puzzled by the lack of effort to assess the potential of some trees to recover by relocating and replanting them, exposing habits of destruction this society perpetuates.

From Mr. One-Third, one’s peripheral vision is directed to Whiteness of Trees, a series of black and white photographs the artist made after super typhoon Mangkhut swept the city in the summer of 2018. They accentuate the presence of injury. The photographs show the trees in an urban setting—some having fallen onto a stone fence, others crawling over metallic railings. One could hear them being pried open by gusty winds and sawed through by human means. They become relics that register their violent past.

From the walls, one perceives the gallery window in the shape of an elongated octagon. The entire window is lined with rippled plastic panels. The panels are detachable. Each one is fitted with a pair of handles, in a scale and form that bear semblance to a riot shield. The installation responds to the increasing visibility of police deployment of the metallic implement in the streets of Hong Kong since the summer of 2019 in multiple ways: it deflects the militarism and sensationalism in images of their deployment, and the heroism and fetishism some attach to weaponry itself. Ho’s panels are brought together not to become an impenetrable wall, but to lend support to each other, however feeble their force. By letting light in, the shields register a faint wish for provisional tranquillity against the injuries inflicted on the other side of the window. They dissolve the opposition, albeit provisionally.

The intensity of the emotional landscape in Ho’s work resonates with Luke Ching’s “Liquefied Sunshine”—the overall title of the show and the title of a particular work I will come back to. I find The Edge of Sky (2019) setting the tone of the exhibition; a pursuit of excess, addressing its absurdity. An exaggeratedly grotesque hybrid creature, half-bird and half-cluster-of-cockroaches, stuck half way through the brim of the glass casing of a street lamp. It at once registers death and birth; death, because the object is in a state of corpse-like stiffness; and birth, for the impregnation of a non-subject and a non-being that haunts the subconscious. There is something primal to it, at once a scream muffled and a medal from a bloody hunt, naked and in the face.

The video Panic Disorder (2019) deals also with excess, but with a visual language in stark contrast to the theatricality of The Edge of Sky. The video is a new iteration of a previous video that the artist has been distributing on YouTube that teaches the public how to make cockroaches with sticky tape. This time, while similarly framed as the close-up of the artist’s hands, the video mimes the process of making without showing the product of their labour. One reading could be that the video is a process of healing for the artist’s personal phobia of cockroaches. It carries an emetic quality; to break away from the fear, one overstuffs oneself with it to the point of throwing up. I find another reading also productive in the context of the dual solo. In implicating the audience’s gaze with the artist’s, the audience confronts an absence the way the artist does; nothing is coming out of the making. Yet, all of a sudden, the audience notices split seconds of a colour image intermittently interjecting the video in spasmodic bursts. The image shows the Hong Kong police calling protestors “cockroaches” that the artist found online. The appearances are too brief for meaning to be recognized. They literally become panic attacks on video-time. The object of fear becomes ambiguous: the more intimate and absorbing the moments of making the absent cockroaches are, the more the imminence of panic attack heightens. The contradiction lies in how this voiceless object of fear turns back onto its maker to haunt him.

Liquefied Sunshine (2014–15) multiplies gestures of erasure and effacement. It could also be approached sonically. Hundreds of postcards with landmarks and icons symbolizing Hong Kong and Taiwan are mounted on the wall. All of them bear slanted white strokes that occupy the entire surface of the postcard. They are semblances of rain. One could imagine hearing the strokes dampening the paper and rain splashing. The gestures—monotonous and continuous—revoke established symbols circulated for the sole purpose of consumption. The artist challenges the idea of authenticity that the iconography invents, and levels their realities by bringing weather into play. When everyone is in the same weather condition in their naked selves, everything is equalized; everything begins again. It is unclear what might generate out of the different rhythms and textures. But the effect is at once unsettling and hypnotic.

Dark Night, White Cloud (2013) embodies space on a different scale. In this series of twelve photographs, the artist’s body becomes a dab of white haze, suspended between rows of benches in the Railway Museum in Tai Po where he worked. The medium is photography, but the process is performative, and the exhibit, both fictional and documentational. The year 2013 was the first time the artist became a security guard by profession. In so doing, he lends radical empathy to the experience of fellow citizens, while expanding the public relevance of the artist by deliberately constraining himself in a particular social capacity. In a Facebook post dated 20 September 2019, the artist said the sense of space for a security guard was quite different because all of a sudden, one person owned a huge and empty space. He found the overnight shift held a particular healing effect. In the images, the artist creates a mythic time that is free from the production time governing public space and the idea of security as a system of procedures. At once humanly, for bringing spontaneous play into the impersonal and routine system, and ghostly, for being ephemeral. The images activate a kind of body politics pertaining to what anthropologist and political scientist Partha Chatterjee calls the politics of the governed: “For the postcolonial theorist, like the postcolonial novelist, is born only when the mythical time-space of epic modernity has been lost forever.” Here, it is the postcolonial artist who seeks micro and local alternatives in the residue of capital-directed space-time. In place of monotony, mythic time conjures worlds beyond the incongruent stories humans tell.

The artist stages himself again as a security guard in Usagi (2013). The title is the name of a typhoon that hit Hong Kong in 2013. An installation of television sets presents multiple CCTV images, designed to be all-seeing, only to have its power challenged by the artist. On this very first day at work as a security guard, the artist enacts dual and competing roles; as security guard on duty on the seeing side of the lens, and as a variable in the form of a human body on the side of the surveyed. The artist is both the subject and object of surveillance. He brings friction to the imperative of the closed circuit to be strategically invincible, not only by critique but also through humour. He turns the impersonal system of security into a playground for human agency: he walks past its gaze, then he runs back and forth under its gaze. It’s not clear if it is exercise or escape. Ching says in the same Facebook post dated 20 September 2019 that “it is by seeing twice that one’s existence is confirmed.” I would rather say that it is by doubling himself as both original and decoy, as appearing subject and disappearing object, that the imperative to confirm one reality mastered by any one power is shaken up.

While their visual language differs, I find both Ching and Ho engaging with the strategy of over-determination to sustain the force of artistic critique. By over-determination, I refer to the way Yugoslavian art collective Laibach used it in the early 1980s , theorized later by Slavoj Žižek as an “’aggressive inconsistent mixture’ of contradictory symbolisms that had the effect of ‘bringing to light the obscene superego underside of the system’ by seeming to over-identify with its rituals.” The critique is precisely in its being able to perform exceedingly ‘better’ than the systems of control themselves.

As I write, circumstances on the streets and the instruments of governance and resistance continue to undergo rapid changes in Hong Kong. Ho and Ching’s works take on varying hues, responding to, and resisting the times. The question of “How is the weather today?”—a departure point of the dual solo—remains a necessity for the well-being of the everyday.

First published on CoBo Social, October 2019.