藝評

Notes and Extensions on Artist Talk with Xiao Lu at Chancery Lane Gallery, 14 September 2019

楊陽 (Yang YEUNG)

at 11:04am on 23rd September 2019

Captions:

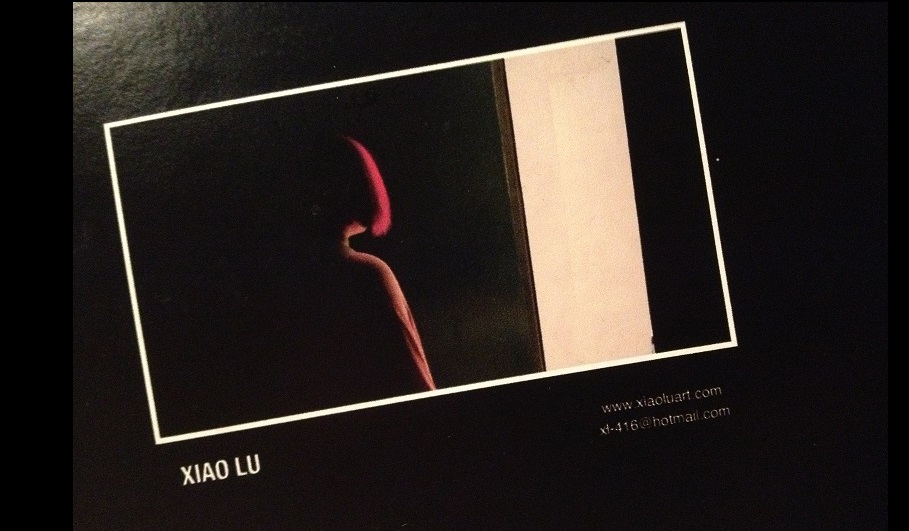

1. Back cover of a catalogue of Xiao Lu’s works published in 2019, printed in China. Photo: © Yu Mo.

2. – 3. Installation views of ‘SKEW: Xiao Lu Solo Exhibition’, 10 Chancery Lane Gallery, 12 September 2019. Photo: Yeung Yang.

(原文以英文發表,題為〈與肖魯的藝術家對話筆記和續寫,10號贊善里畫廊,2019年9月14日〉。)

We began with Skew, the opening performance she conceived for Hong Kong on September 12, 2019. She stepped into the acrylic pyramid, sealed on the side. She had us pour water dyed in red into the vessel from a small round opening at the height of her face. After 20 minutes or so, she gestured that the window should be closed. The water was ankle high. She held up, with her head and toes, the confinement she imposed on herself. She began pushing and falling, pushing more and falling more heavily. From the outside, the sound of her feet sliding, her palms scratching, was all muffled, heightening the intensity of the confinement. I thought I became a bystander, a mute accomplice of her suffering. I was worried this may last longer than I could take, and longer than she could take. There were faint screams out of suffocation. It was not acting, but living the confinement and the yearning to be free in one stroke.

Xiao said she had wanted to be able to topple the entire pyramid over – that was the imagination she had for the performance. Circumstances and design allowed her to break open the triangular panels one after the other. Soaked but not defeated, panting but fearlessly so, falling but majestically present, her body becomes both a site of burden and a site of release.

In June this year, Xiao came to Hong Kong and was moved by the June 4 candle light vigil at Victoria Park. She became aware also of the current movement that roughly began in June. She began thinking about Skew, which carried elements common to many of her previous ones. For many years, her performances have been built around notions of confinement and breaking through by crossing boundaries that are physical and symbolic - running away from the authority of religion and jumping into the water in Purge (2013), chiseling and punctuating the ice in Polar (2016), getting drunk and becoming non-sensical in Drunk (2009). Some of these performances involve varying degrees of deliberate self-affliction like Skew (2019), or risk injury like Bast Paper room (2013) in which she refrained from eating for seven days and nights, and Holy Water (2017) in which she downed seven bowls of Moutai (53% alcohol) walking on 27 blue acrylic plates placed as a diagonal line in open space. How does she choose the afflictions? The artist emphasizes the importance of following her state of being at the time. In 2018, it became clear to her that suppression of the freedom of artistic expression in China was sharply heightened, which compelled her to make Coil. In the performance, she placed herself in an acrylic box with holes. The audience stuck burning moxa sticks into the holes, filling up the box in smoke, bringing the artist to tears and to the point of choking and suffocation. She wears and burdens her entire self with the power system, enacting it. The performance was made in her studio because it was not accepted to be made in any public place or private museums.

While many performances invite an “excess” to impregnate the moment, letting it spill over to reach a state of “self-oblivion”, “the irrational” and “transcending the normal”, as Xiao would describe in an interview, there are particular parts of the body that I find her prioritizing. The skin as the largest and the most expansive organ tends to be prominent: porous to outside influences, making a person vulnerable. For instance, in Drunk and Holy Water, Xiao’s entire body crawls, rolls, stretches, becomes porous…but at the same time, it is not trying to touch something that can be located or has a fixed form. The more exposed it is, the more it erases the distance between the body and what it touches, and the more something withdraws – the skin becomes “the trace of its own withdrawal”, a phrase Cathryn Vasseleu coins in Textures of Light (1998). For me it’s very seductive to think of the skin as both available and accessible to be touched, but also presenting a blindness that is like the blindness of a caress, which does not only belong to the female body. The subjectivity of the artist becomes a kind of sensibility of the skin.

I find Xiao Lu’s work strong in that there is no “self” or any unified subjectivity to be sought, despite the fact that they arise out of your very personal experiences that she honestly talks about, too. I think of feminist philosopher Luce Irigaray’s idea of “divided existence” – the feminist sense of self is not a unity, and it is a subjectivity that “knows nothing of itself”. Irigaray argues, “Without an objective orientation woman’s relation to being remains an affective immediacy somewhere between an instinct and an intentionality that has no object.” To know nothing of itself is a gesture of radical hospitality. It knows nothing of itself as a unity or a priori, but always being open to what could be. This division is the result of many factors, but perhaps prominently, how people lay claim on oneself – one’s body, dreams, desires etc. This is also why I prefer to keep a distance from comments about Xiao’s works as showing “contradictions”– a bride without a groom, creation and destruction, etc. Contrary to some understanding of feminism as emphasizing the feminine morphology/ structure/ shape as a receptacle, her practice is full of multiplicity. She lives reality as it is, and to the possibilities and potential in life, that any unified subject cannot occupy.

The idea of the personal she repeatedly coined could also be shaken up. There is a frequently circulated dichotomy about how men engage with grand narratives like social or political issues and women, private and personal ones. I think it’s misleading to read Xiao’s work this way – while she admits a lot of her work is based on personal troubles, her way of acting them out opens them up, daring others to become accountable for them. It is in this sense her acts are heroic, but not grand that can be exhausted by grand narratives. Grandness is what others seek to define an artist after-the-fact. Truth is how she arches her own narrative.

In recent years, Xiao finds her letting go of the decades of emotional struggle. In the recent performance Tides (2019) in Sydney, she plants bamboo poles at a beach, addressing the connection between China and Australia, where she stayed for eight years after leaving China in 1989. It is a different dialogue – between her and nature, from between her and all kinds of power that is oppressive, in impossible dialogues. The introspective self-dialogue however has never stopped. Around the time of Bald Girls, she started reading up on feminism and women’s rights. She started undergoing a change, paying attention to the lives of other women. It’s “less direct”, she said. Other women became a new subject in her art practice. (interview in 2013 by Monica Merlin, Beijing) But after studying the ideas, she realized she is not driven by concepts or theories, but materials. She finds it also hard to accept such labels as “feminist artist”. She knows herself otherwise. In the retrospective catalogue, Xiao disagrees with Simone de Beauvoir, who says in The Second Sex “Women are not born; they are made.” Xiao instead says, “In my experience, women are born. Women’s innate maternal character endows the with a faculty of self-sacrifice. As long as she is willing, she can give all of herself. The popular saying goes: ‘Man is heaven, woman is earth.’ However, this heaven must be a real heaven. Under a heaven like that, the wide earth can embrace everything for heaven, heaven and earth become one, surely the optimal situation. What need is there in that case to go and overturn heaven?”

One has to be very strong, physically and morally, with tremendous inner strength and ardor to be doing such works of emotional intensities. I asked Xiao how she prepared herself for them. “Emptying my mind so that it is free. Time – at least four months.”

I didn’t have the chance to read this out for her in her presence during the artist talk. But many times I did, and I know I will, in my solitude, knowing I would be baffled in the long-run: “The conscience of a human being is like the nucleus of an atom. Only you yourself can know the core of your nucleus. It may burn, it may emit light. But it can also explode.” (Xiao Lu, tr. McKenzie, 2010: 105)

Next time I see her, I will ask her “What is the latest lesson on life you’ve learnt?” And how you would like to be remembered, if at all. Or, how is she preparing herself to die – having killed herself so many times.

A poem that her friend wrote in Chinese, her voice reading it out loud in its strength, closed the session.