藝評

more than just a reversal

楊陽 (Yang YEUNG)

at 11:59am on 22nd December 2018

Captions:

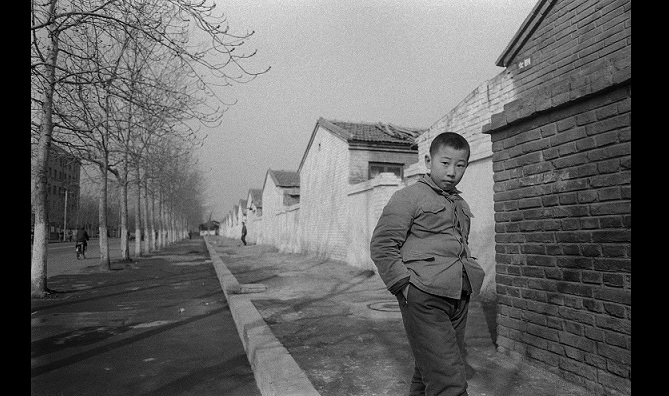

1. Joseph Fung Hon Kee, Beijing, 1980

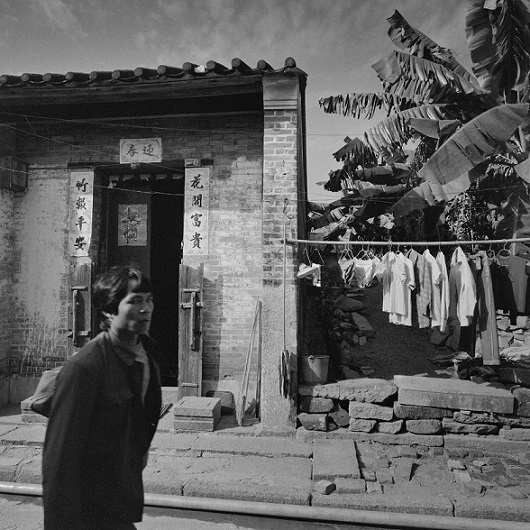

2. Joseph Fung Hon Kee, Lanzhou, 1981

3. Joseph Fung Hon Kee, Shenzhen, 1982

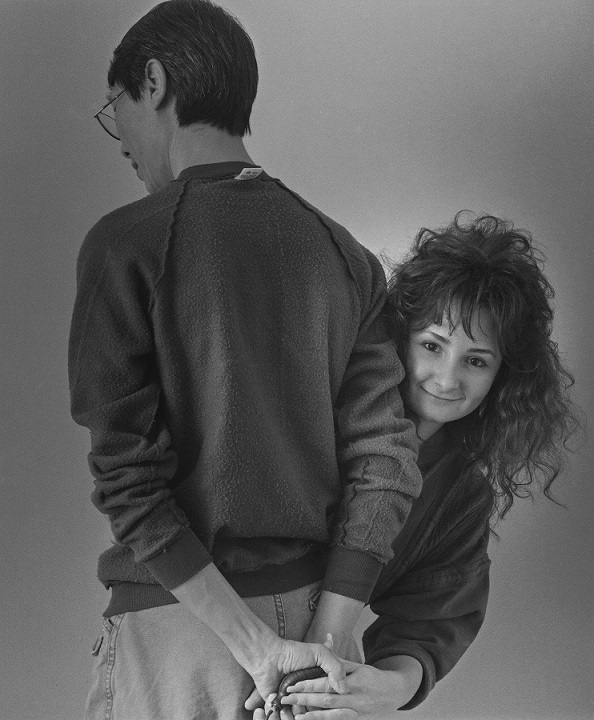

4. Joseph Fung Hon Kee, Joanne Hudlick & me

(原文以英文發表,評論馮漢紀的攝影作品。)

How does an artist decide it is time to make a self-portrait - how many times in a lifetime? what may hide, what may show? In Joseph Fung’s body of work in this exhibition, images that the artist makes of himself are not readily noticeable. But marginality is never a good reason for disregard. I find several images registering the artist’s particular approach to the self-portrait, that I would like to focus on. In these images, the artist is interested in how others perceive him. By this I do not mean the artist seeks to fashion himself with a public persona for others to receive, but that the images present an understanding of the self portrayed as an image of being situated among others, always already affected by how others receive him. The quality of this double receptivity - his receptivity for others, and his receptivity for others receiving him - offers a hinge for understanding his photographic moments.

1

A man is at the driver’s wheel in a car at rest. He is glancing out of the window. Carrying a smile with a tinge of anticipation, he is at ease without being self-conscious about it. In this serenity, the giant lion sculpture at the back appears small; its apathy is accentuated. This man was Fung’s driver on his trip to Lanzhou in 1981. This is no trivial fact - instead of positioning himself as a disinterested photographer encountering a random person on the street, the artist depicts the beginning of a relationship. He is not egoistically looking for his influence on the man, but is attending to the eternity of the affective encounter. This is an eternity that is not forced out of built monumentality (like Mao Zedong’s stylized self-celebratory images and figurations) but arises in a moment of serendipitous connection.

In the series Beijing 1980, another face jumps out of the frame. A boy in a heavily padded winter coat walks past the camera. With both hands in his pant pockets, he is caught in an adult gesture of confidence and pensive composure. His body is held up by the verticality of the street. His face is calm and radiates in the sunlight, making his presence majestic and appealing to the sense of touch. His slightly tilted head suggests that Fung, who is five feet ten inches tall, must have been bending or kneeling or lowering his camera so that he aligns the lens with where the boy’s gaze is directed. Fung makes the effort to be with him on his bodily level. In so doing, he equalizes the social space between him and the child, despite physical disparity. The action registers an instance where the artist is as interested in how the boy sees him as how he finds the boy.

A man in the Shenzhen 1982 series also looks back at the artist, but in an anxious gaze. He is in the middle of a brisk momentum, his face and body slightly squeezed. This tightness suggests he is more alienated from his surroundings than the boy on the street. In the split second that he catches sight of the camera, his eyebrows twist and from there, a narrow and slanted glimpse extends. Is he interrupting the photographer’s attention directed to the house, or is the photographer interrupting the man’s journey? The ambiguity keeps the reciprocity of the gazes alive.

These three images share a similarity: it is as much the persons as the photographer’s subjects as they are fellow human beings carrying an image of the photographer in their perception that the artist captures, which brings me to his Chicago portraits. I would like to focus on the set of three where a portrait of a woman is paired with a double portrait with the photographer himself in them.

2

The circumstances, according to Fung, is that he was reflecting on the claim that the photographer who triggers the shutter is always in power, subjecting the photographed to a passive position. His intention to transfer this power to the photographed results in the set of double portraits. One image of the three shows the shutter in the hand of the sitter; another shows Fung and the sitter holding them together while Fung has his back to the camera; the last image does not make the shutter visible. The power Fung refers to could be interpreted an extension of masculinist desire regulated by compulsory heterosexuality. To question the photographer’s power is also to question masculinist power. Have these images done so? If, according to Judith Butler, “gender is the repeated stylization of the body, a set of repeated acts within a highly rigid regulatory frame that congeal over time to produce the appearance of substance, of a natural sort of being,” (Butler 1990: 33) and that to interrupt this process, gender needs to be rethought as performative (Butler 1990: 24-5), one reading of Fung’s portraits might be that they are incomplete. They reproduce masculinity and femininity as complementary in composition, hence reproducing received heterosexuality. For instance, in one image, the female sitter poses as if she were a nymph hiding behind and popping halfway from behind the male body - the central pillar of the photograph. In contrast to the fluidity of the female bodies, maleness presents itself as hard and angular. The subjectivity the artist intends to highlight in his female sitter is intelligible only “through its appearance as gendered” (Butler 1990: 33). The process of resignification may have begun but is not yet transformative. To be fair, however, this incompleteness opens up more paths for interpretation than just the switching of subject/ object positions as points and counterpoints can exhaust; it shows the complexity of that which the artist produces and envisions.

It is not difficult for any ordinary viewer to backtrack and imagine the photographer’s body and conscious self moving from behind the camera into its frame. In following his move along this line, the viewer participates in the artist’s production of an excess that demands a different thinking of the photographer’s self and his relation to his sitters. I propose that this excess comes in two forms. First, in presenting the double portraits of him with his sitter and the single portraits of his sitters in pairs, the artist shows the choices he makes: from singular vision directed to his sitter to a doubled vision directed to the sitter and himself. The photographer’s gaze is present on both sides of the camera, conventionally taken to be two worlds. The vision is doubled when one imagines moving along a continuous line joining the two worlds. This is also a line with which viewers keep the mental inference that the artist is still behind the camera while being in front of it at the same time. It is an invitation that viewers regard the worlds as one. The stubborn persistence of this line produces in viewers a sense of disorientation: is the artist looking back at us in defiance or nonchalance? There is no story or narrative to substantiate what is seen. The artist becomes doubly inaccessible: as a face within the frame, and as absent but present behind the camera.

The excess is also in compounding the sense of time. Letting his sitter make a portrait for herself and showing the result is different from letting her make it for herself with him as company and showing the process. The latter case includes how she looks at and looks for the photographer, who is involved in and co-inhabits the ‘now’ with the sitter rather than being an author who comes before the image in time. The photographer puts himself into the same temporal order of reality as the image. The multiple and overlapping lines of gazes looking for and scrutinizing each other - viewers included - creates a space of contention. A ‘work’ suggesting the artist’s intention effectively transforms into a ‘text’ affected by contingencies, contexts, and circumstances to be read. In what John Berger calls a “process of rendering observation self-conscious,” (2013: 25) the photographic moment that sets up a boundary between the worlds behind and in front of the camera is marked and opened up. For the artist, this is a process of unknowing and unlearning about a self that is perpetually displaced, misplaced, and delayed.

3

In an essay in memory of Roland Barthes, Italo Calvino recalls Barthes’ refusal to define a “photographic universal” (1997: 306). He says Barthes takes into consideration only those photographs “that I was sure existed for me.” I understand the ‘for me’ as not a claim Barthes makes about him bestowing meaning upon the photographs that are personally valuable to himself, but that the photographs matter when they confirm his sense of being in the moment, and that the being is also always already a becoming. To refuse the universal is also to ask, for Barthes, whether there cannot be a new science for every object, and to show that it is something possible to seek. Or, as an artist puts it in a different way, could there not be a unique book list for the understanding and articulation of each and every artwork?

In penetrating into the social space his lens participates in making, Fung lays bare the lines of seeing he lives through, not unlike how anthropologist Tim Ingold says of how life is consisted in open-ended lines that offer relationships, histories and processes of thoughts along the way, rather than disjointed dots in time. (2016: 174) In touching the lines that bring incommensurable distances momentarily together, Fung burdens us to look closely into faces that have come along our life’s way, in which we may find our own - a powerful, responsible, and intimate endeavor, a reminder that looking away is no longer an option.

References:

Berger, John. 2013. Understanding a Photograph. Ed. Geoff Dyer. New York: Aperture.

Butler, Judith. 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge.

Calvino, Italo. 1997. The Literature Machine. London: Vintage.

Ingold, Tim. 2016. Lines. A Brief History. Oxon & New York: Routledge.

First published in the exhibition and catalogue of Time/ Space: Brief as Photos – Dialogue between Joseph Fung and his contemporaries, December 2018.

原文刊於「時/空:暫如照片──馮漢紀與當代攝影對話」展覽場刊,2018年12月。