藝評

Ai Weiwei – absent as usual

彭綺雲

at 11:06am on 20th January 2012

As Taiwan exercises its right to go to the polls this week, the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei’s first solo exhibition in a Chinese-speaking nation draws to a close. Since his 81-day detention in April 2011 by the Chinese authorities, Ai has gained a popular moral authority that has ensured that his actions, non-actions and actions-in-his-name have attracted a level of attention and intent that eclipses that of any other figure in China today. The release of a collection of his influential blog postings in English, Ai Weiwei's Blog: Writings, Interviews and Digital Rants, 2006-2009 (MIT Press), edited and translated by Lee Ambrozy, and Alyson Klayman’s documentary “Ai Weiwei: never sorry” (aiweiweifilm.org) have done much to contribute to this.

The exhibition “Ai Weiwei absent” at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum (TFAM), planning for which predates his arrest is, in action, a bold challenge to China’s muting of Ai domestically where he has been charged with tax evasion and remains unable to travel without permission. This last condition is cited as the reason that the artist was not invited by the museum to his own exhibition opening at the end of October 2011. Inevitably, the exhibition has provided a convenient platform for a whole range of issues from artistic freedom and freedom of expression to the plight of the ordinary man in China, and access to basic protections of human rights that will be hard to divorce from any current or future discussion of Ai’s work.

The significance of the exhibition lies less in its framing in Taiwan as an alternative model of Chinese political rule, and more in the context of Taiwan as an alternative model of Chinese cultural activity. Ai’s exhibition opened in a city where just a few miles away the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Revolution of 1911 was being celebrated in a series of exhibitions featuring treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei collections. Ai’s work benefits from being seen in such close proximity to one of the world’s most legitimate repositories of Chinese cultural capital which is, for now at least, unimaginable anywhere else.

While one might comment on the museum’s self-conscious ambivalence towards the reality of what Ai has become beyond the art world – alongside reporting of criticisms that political and civic leaders had not visited the exhibition – what is important about this exhibition in the end is that it presents Ai first and foremost as an artist.

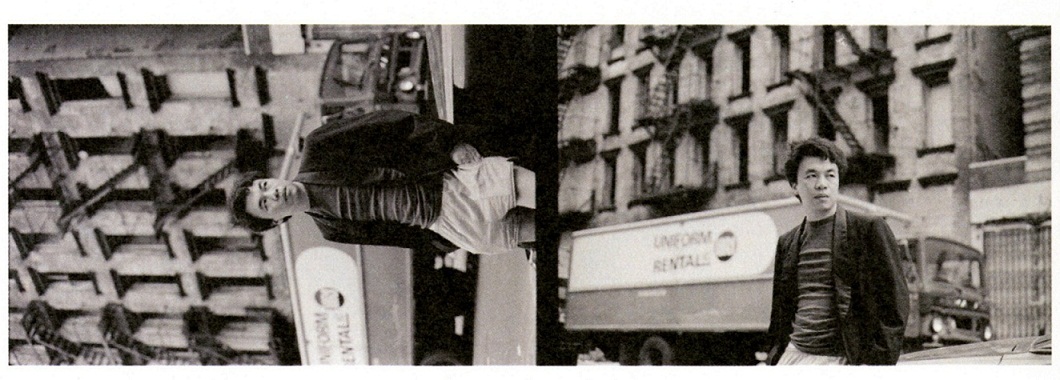

Tracing a twenty-five year period from the artist’s emerging in New York to his most recent works including one commissioned for the museum. Ai’s zodiac animal heads, which were shown last year at Manhattan's Grand Army Plaza (fig.4) are installed in the lobby of the museum but the exhibition really begins with a series of 100 photographs dating to the 1980s and early 1990s, documenting his years as part of a group of Chinese artists and intellectuals in New York’s East Village, and his subsequent return to Beijing where he established the short-lived artist's community, known as Beijing’s east village “dong cun” where the artist Zhang Huan performed his works “65kg” and “12m²”.

Ai's photographs reveal an almost anthropological interest in those living on the margins of society: the self-exiled congregation of artists and friends that passed through his East Village apartment (Bei Dao, Wang Keping, Tan Dun, Hu Yongyan, Chen Kaige, Jiang Wen, Liu Xiaodong, Xu Bing, Chen Danqing just to name a few); the homeless; and those driven to protest. His images of expressions of public resistance and protest in late 1980s New York have a particular resonance in light both of his own circumstances, and of the current 'occupy' movements. The television phenomenon of “Beijingers in New York” that sought to depict the lives of contemporary Chinese émigrés – scenes from the filming of which are included in the exhibition – showed the real anxieties and disappointments of living in America, and also served as a cautionary tale. (fig.5)

Ai’s photographs were last shown at the Asia Society in New York where many in the art community were moved to protest Ai’s detention, but there they lacked the context of his work, and set among the grand buildings of the Upper East Side’s Park Avenue, viewing them was an uncomfortable, almost voyeuristic exercise. Including them as part of this exhibition creates a riveting and intimate biographical framework for the seventeen video and installation works dating from the last decade. Shown together, they are a powerful elaboration of Ai’s pre-occupation with authenticity both in material and abstract terms, anger at the appropriation of history, and playfulness in working out ideas about what it is to be an artist, and the boundaries of material and artifice.

Many of Ai’s works shown here are already well-known and to some extent iconic: the series of three photographs showing Ai “Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn” (1995) for example, and his digital expletive in “Study of Perspective: Tiananmen Square” (1995). The photographs of the earlier period make sense of these works: Ai ensures that you are aware that the image, and the artist in it are a construct and that you, as viewer are being manipulated. He is quite quite transparent about that.

Ai’s own appropriation of materials from the past in creating works like his monumental “Through” (fig. 2) using discarded beams and pillars of Tieli wood from demolished Qing dynasty (1644–1911) temples, and tables, or in painting over Han dynasty (206 BCE-ACE 220) pots using recognisable commercial brands (“Coca Cola Vase”, 2010) say more about the facade of urban development and “lifestyle” in contemporary China than any photograph can. The authenticity of the ancient, and the desecration of it in the name of art should be no more shocking to us than what is happening to the past in the name of an aspirational future in China today.

One of the more personal notes in the exhibition concern Ai’s inclusion of photographs of his father, the poet Ai Qing, elderly and frail in 1994, captioned “Ai Qing’s last days at home” and the juxtaposition of Ai’s “Map of China” (2004) made of old Tieli wood with a short poem by his father dating to 1937. The blurring of lines between the artist’s intellectual and emotional life can perhaps be traced to artists such as Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol whose work he has himself photographed against when in New York.

Marble, which has its own classical and nouveau riche layers of meaning, is used by Ai in the production of works of altogether darker intention. In “Surveillance Camera” and “Helmet”, both 2010, Ai appears to be commenting not just on a state’s inviolable right to surveil its citizens, but also on one of the more volatile issues in China today: worker’s protections and by extension, compensations. Powerfully simple in conception but devastating in their impact.

Perhaps the one true surprise of the exhibition is Ai’s “Ruyi”, 2006 (fig. 3). It might be related in medium to the lite and humorous “Watermelon” of the same year but its transformation of porcelain results in something more lascivious and grotesque. The discovery of the way and means to make porcelain is one of China’s great achievements, and Ai exploits the material’s qualities as far as it can go. Moulding it into an irregular ruyi form (a purely decorative object of the Qing period, usually made of jade and often gifted to wish the recipient good luck) built up of human organs, Ai paints his ruyi in bright gaudy colours beneath a glaze so wet-looking that it appears to quiver fleshily. Again, proximity to the National Palace Museum nearby allows viewers to see the similarly eccentric but arguably less gaudy Qing versions for comparison.

The exhibition concludes with the monumental “Forever Bicycles” (fig. 1) produced for the TFAM and named after the brand of bicycle. A sign outside the gallery assures visitors that the air quality meets health and safety standards, recalling some of the difficulties encountered in the original installation of Ai’s sunflower seeds in the Tate Modern Turbine Hall in 2010. There, the dust of the porcelain seeds when walked upon, as the artist intended, was considered too toxic, necessitating a containment of the installation. Both installations unwittingly demand consideration of the long-term safety of those exposed to toxic materials in the process of industrial production, and environmental concerns. Joined together as if a scaffold rising up to the gallery’s ceiling, Ai’s bicycles are an apt metaphor for his pessimism about China. Tethered together without seats or handle bars, these bicycles have been castrated of their function and are unable to transport anyone anywhere.

Ai Weiwei may have been absent but his art proved ample compensation.