藝評

we may never know, but it is worth trying

楊陽 (Yang YEUNG)

at 10:30pm on 15th November 2016

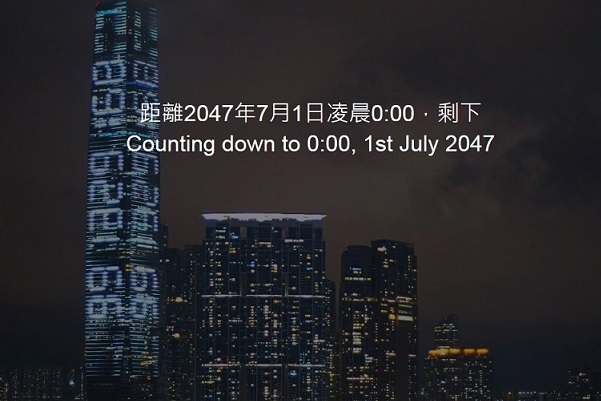

The image was taken from Counting down to 2047 webpage.

(原文以英文發表,評論「感頻共振」展覽抽起黃宇軒及林志輝作品事件。)

The withdrawal of the artwork by Sampson Wong and Jason Lam from the exhibition Human Vibrations in “The 5th Large-Scale Public Media Art Exhibition (2016)” offers a valuable opportunity for learning how to debate competing common goods: in this case, with art being staked out to find its place in society. I hope to join others who have initiated the discussion with a few paths of simple-minded thinking.

A public statement co-signed by chairman of the visual arts committee of the Hong Kong Arts Development Council (presenter of the exhibition) Ellen Pau and curator Caroline Ha Tuc, and a subsequent personal statement by Pau which she made public state that the withdrawal results from the artists’ violation of an ‘original agreement’ based on ‘confidence’, ‘respect, and ‘trust’. This is framed as a violation of professionalism, consequential to the future of ‘our profession’, putting it “at risk [of] any future possibility to work further in the public space.”

Who is this “our” in “our profession? One interpretation could be the signatories bound by contract with the exhibiting artists in this particular project. Another interpretation could be everyone in the profession of art. The choice we make in how to read the ‘our’ affects how we understand the reason the statement gives for the withdrawal: “After the opening ceremony of the Exhibition held on 18 May 2016, the artists changed the title and statement of their work, and publicized these changes, without consulting the curator nor HKADC.”

If read, firstly, as a violation of the contractual conditions, the statement presents two puzzles – 1) with regard to how an art work and its scope are defined, and 2) with regard to the working relation between the contracting parties:

What are the terms in the contract that set out which ‘changes’ of the art work are bound by it and which ones are not? This question relates to how the contract defines the duration and scope of the art work. Do the contractual conditions apply to the art work insofar as it is fixated in the form for display in the exhibition, or beyond? Given that the art work had been declared open and shown in the agreed venue, how far were the artists bound by the contract to interpret and communicate what they had done outside of the exhibition? In the contract, is the artists’ interpretation of their work regarded as part of or a continuation of the work or as separate from it? Artists may not be the best interpreters of their own works (hence a supporting system including curators and writers to do so), but could artists be prohibited from doing so by contract? To say that the interpretation of a work is a mis-interpretation (as reduction, distortion, factual error, etc.) is one thing; to say that it is damaging in a general way and therefore justifies prohibition is another. The latter opens a door to the additional regulation of free artistic expression that is already regulated by law, for instance libel. What information do we need to make good judgment on how far the institution could regulate the interpretation and communication of an art work in public, conducive to is understanding?

While the contract binds the contracting parties to ‘work together’, how far could it ensure that they work together well? The earlier statement points to the artists’ failure to consult the curator and presenter as a violation of the agreement to work together. Subsequently, Pau mentions in her statement that the presenters had tried to communicate with the artists, but because of the lack of time, had to make the decision to withdraw. What limits the time for making good communication? What goal is being directed by time as a source of pressure, prompting response as if there were an emergency? What is the lack of time for? Decisiveness can be a virtue, but decisions presented as a necessity without good reasons beg questions about whether judgments on perceived risks are well guided and not prompted by, for instance, institutional self-censorship, or whether judgments on the propriety of deeds are matched by proportionate response. Common sense tells us that good communication is a crucial part of working together. The failure of communication can be consequential to the integrity of the project – its mandate and artistic quality. However, communication is always mutual. Are there compelling reasons in this case to burden the artists as the only parties responsible for communication failure?

It is not clear what exactly happened between the contracting parties with regard to the terms of the contract, leaving many questions unanswered.

Emergencies may demand swift action, but swift action does not require calling thinking to a stop. What is required of emergencies is the composure to consider competing principles the decisions are intended to uphold. If professionalism and artistic expression are competing principles in this case, both having the potential to contribute to a viable future for art, what have been the considerations that lead to the conclusion that the former should override the latter?

The absence of the language of art in the statements is puzzling. As challenging as it may be to defend bad art, bad art is part of professional life of all those who work in art and part of ordinary civic life. Even when a work has gone bad, the parties presenting it and arguably the curator in a primary way have the duty to explain to the public the stakes on all sides – artistic aspects included. Would public understanding have been facilitated if the curator had given artistic reasons for not being able to work with the artists as the circumstances changed? Would the negotiations have been different if other artists involved in the exhibition were brought into the decision-making process of withdrawal so that they were offered the chance to be accountable to the project as a community? This relates to the second reading of the ‘our’ in ‘our profession’ as all those in the profession of art. I wonder what puts our profession at stake, if at all –the art work, the violation of the contractual agreement and the violation of trust as claimed, the withdrawal itself, or many other things that have happened along the way? What hierarchy and economy of blame have been activated in this case? In fact, I wonder if our profession is at stake at all, or if this is but one of the many ordinary occurrences with an ordinary degree of risk arising out of the way artists work.

How are trust and ‘our profession’ as a profession related? The statements portray trust as a component of professionalism; they claim that the violation of trust puts our profession at risk. I am not sure if this communicates what our profession is and its risks as part of the package. Trust is a messy human affair and is a slippery term. No one can deny its worth in public life, but everyone is aware that it is only in the perfect world that there is unconditional trust. It is arguably for this reason that contracts are made, and trust, managed in the profession in particular ways. Trust is also a norm in civic society, but not the only one nor the over-riding one. For a society that values the individual’s freedom of expression, a degree of distrust is in fact needed towards, for instance, government interference to ensure that trust will not become overly secure to make us as citizens inactive to govern, so that the activity of building and maintaining trust remains ongoing and formative. In some societies, necessary dissent to ensure freedom of expression is routinely regarded by those in power as disrespect, hence publicly denounced as being offensive. But does the feeling of being offended justify regulation? [1] If the feeling of being offended alone becomes a reason for regulation, what are the implications on the possible future of the art profession and its place in public?

Instead of grounding itself on trust, I propose that professionalism is an ethics maintained not only by temporary and project-based contractual terms. Professionalism depends on an account of enduring codes of conduct with ethical bearings that members of the profession agree to continuously abide by, to self-regulate with, and to deliberate collectively in response to change, for the sake of not only ensuring the profession’s survival, but also its contribution to society, for if there is no society as context from which and for which the profession acts, there would be no object for this professionalism to apply to; professionalism can give itself to nothing. A complex situation requires complex response; it is precisely from the standpoint of the profession that complexity can find articulation to contribute to public understanding of the truth and challenges of the profession. To choose not to do so is to exercise the kind of power already established, and to invite the public to hope for a future that is overly determined by what is already in place – as signaled by the silence of the venue partner and the curator in this case. Are we to hope for art that would align with the narrow window of trust the presenting parties could offer, or could there be negotiations on how much the presenters could take risks with the artists together, as a professional community with everyone having equal power, with trust being generously given for the dilemmas, failures, risks etc. that art is always already?

Art distributes a different kind of hope for its potential to ask questions about reality (if not always, at least with a more resilient potential to be able to). This is what is precious about art as a human endeavor. Artists can give life to this kind of philosophical work when they are honest with the way they succumb to anxiety and self-doubt. In this current case, the artists have done precisely this: because a particular public space and the opportunity to show art there is regarded as precarious, the artists take the risk and treat the chance as now-or-never. What about the institutions? On what principles have they negotiated for the project? How have they prioritized and wrestled with a hierarchy of values in the negotiation, including the short-term opportunity for showing, or a longer-range view of contributing to a public culture that is truly open to and willing to recognize the value of art? The statements have not shown the principles for negotiating for the project, but it is clear that compared to the artists, the institutions, in the silence of those having one-sided control over public space, are in a better position to determine what can or cannot show; this exercising of power has managed to substitute for the public need of a convincing argument. Is this unequal relation of power a choice worthy future for art and public culture?

What would a vision of future with all art sharing equal aesthetic right (to borrow Boris Groys’ idea) look like? I imagine beginning from a different evaluation of privatized and intensely commercialized public space: if it had not been the exaggeration of the value of placing art in such places as the ICC or equivalently spectacular and iconic places as if they were frontiers to be conquered, would there have been less fretting about losing the opportunity as if guarding some treasure chest? If such places are not seen as exalted, but one part of many that contributes to the long-term project of the equal aesthetic right of all art forms to be not only present in but making and inhabiting all public spaces, would there have been a higher chance that the hierarchy of values currently circulated could be opened up and re-negotiated? When we start thinking through enduring values for the future of art, we nurture a kind of responsiveness that aims for understanding rather than measuring. It is also a kind of responsiveness more likely to enrich the thinking of art, more likely to nurture the steadfastness necessary for regulating undue insecurity and knee-jerk actions, which could be as unprofessional as the artists in this case are opined to be. To build trust for the future, putting trust or the lack of it on public trial offers little help.

In Hope, new philosophies for change, Mary Zournazi speaks of hope as “what sustains life in the face of despair.” It is “not simply the desire for things to come, or the betterment of life. It is the drive or energy that embeds us in the world – in the ecology of life, ethics and politics.” This is distinguished from the kind of hope worked out in a negative frame based on fear. This negative kind of hope “masquerades as a vision”; it is “a kind of future nostalgia […] charged by a static vision of life and the exclusion of difference.” [2] As a feeble voice in the profession, I am asking of the institutions and curators to be in tune with the kind of hope that artists have always been conjuring in a dynamic realm of practices and processes. Hope begins now and not in the future, just as public well-being begins with every gesture arising from the present; it is not perpetually delayed. (This is often how hope and optimism are distinguished.) The language of professionalism for art is not isolated from the language of all that art is; the latter does not aspire to a kind of professionalism that focuses only on what to make, but also on how and why to make it as a purpose of human life, not a function serving a closed system. No policy could be damage-proof, but we could work for one that seeks adequately deliberated common goods.

Notes:

[1] This idea is inspired by Jeremy Waldron’s The Harm in Hate Speech (Harvard University Press, 2012).

[2] See Zournazi, 15.

Work Cited:

Zournazi, Mary. Hope, new philosophies for change. Annandale, NSW: Pluto Press Australia, 2002. Print.

This is a revised version of the original first published on the Art Appraisal Club website, October 2016.