藝評

Europe-Asia: Re-Orienting Circuits of Influence

Helen GRACE

at 1:21pm on 18th February 2012

Captions:

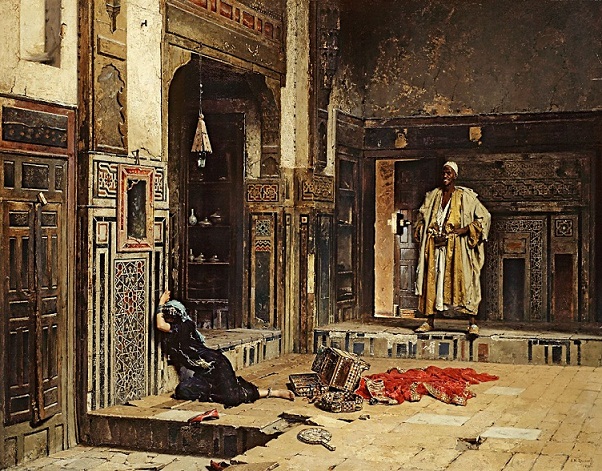

1. Roessov, Bought for the Harem, 1891.

2. Vereshchagin, Dervishes in festive clothes, Tashkent , 1869.

3. Vereshchagin Politicians in an Opium Den, Tashkent,1870.

4. Vereshchagin: The Doors of Timur (Tamerlane), 1872, State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

(原文以英文發表,評論俄羅斯的東方主義繪畫1850-1920。)

Europe has recently rediscovered Orientalism with a spate of new shows and up-coming auctions and a burgeoning taste for the characteristically bright genre scenes and photographic realism that is typical of the style. Noteworthy exhibitions over the past year have included Orientalism in Europe: from Delacroix to Kandinsky that opened in Brussels in October 2010, travelling to Munich and Marseilles through 2011, The Spectacular Art of Jean-Léon Gérôme at the Getty in 2010 and then the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, and the Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid in 2011, and L’Orient des Femmes, a costume show selected by Christian Lacroix at Quai Branly, that opened in Paris in early April 2011.

The renewed enthusiasm is no doubt helped by startling auction results – such as the $US36m sale at Sotheby’s in New York in November 2010of Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s 1904 painting The finding of Moses, a highly theatrical work that inspired Cecil B DeMille’s script writers and designers for both Cleopatra (1934) and The Ten Commandments (1956).

Leading this new demand is the emergence of notable Middle East collections and collectors, including the Moroccan and Saudi royal families, proud to display their good taste in Europe, as well as dealers and auctioneers setting up shop in Istanbul, Doha and Dubai. Nicholas Tromans, curator of Tate Britain’s 2008 Lure of the East show that later traveled to the Sharjah Art Museum in Qatar, has noted that “No sooner had the British left the Gulf as imperialists in 1971 than they returned as art dealers.’

If Edward Said’s influential work brought Orientalist painting into some disrepute in the 1980s, it is no small historical irony that the new celebration of Orientalism is being led by the Middle East itself and that a new taste for oil painting has been fueled by global demand for oil.

To date, much of the attention has focused on French and British Orientalist painting but arguably of more historical interest are the circuits of influence that spread further north and further east into the resource-rich republics of Central Asia. So the show which has the most to offer in a fresh reappraisal of Orientalism is Russia’s Unknown Orient – the show that opened the newly refurbished Groninger Museum in the Netherlands in December 2010, continuing into May 2011. The show focused on Russian, Central Asian and Caucasian work, giving us a previously under-appreciated insight into the links between European Orientalist painting and Central Asian visual culture. Later these links would be filtered through Soviet socialist-realism before arriving in China in the 1950s, and providing the academic tradition that has so influenced contemporary Chinese painting.

The exhibition presents an entirely fresh perspective on work from Armenia, and Central Asia as well as giving us a sense of the spread of the academic tradition within the Russian imperial project during the nineteenth century. Importantly, we also see what happened to the Soviet avant-garde after socialist realism became established. Most notably, the show’s careful selection makes visible some quite profound differences between British and French Orientalist painting and its focus on the titillating aspects of the harem as opposed to the less sensationalist and more social and ethnographic concerns of the Russian and Armenian artists shown here.

This is most clearly signaled in the precise placement of Aleksandr Roessov’s 1891 Bought for the Harem and Stanislav Chlebovski’s 1870 High Drama in the Harem outside the entrance to the main body of the exhibition – a move which takes a deliberate distance from the exoticism of this tradition of Orientalism, more well-known in, for example, Gérôme’s and Delacroix’s somewhat theatrical treatment of the subject. In the former painting, a domineering lord stands over his new purchase, a cringing female slave and in the latter, eunuchs enter the bedroom of the sleeping Sultana, ostensibly to murder her in a kind of Scheherazade scenario. Both paintings are meticulous in their detailing – in the depiction of elaborate blue ceramic wall panels in the Chlebovski work (Chlebovski was another of Gérôme’s students) and in the force of oil paint in Roessov’s work, with its accuracy of rendition of surface, so that wood, stone, marble and ceramic tiles appear to have been actually used instead of oil paint. Unkempt surfaces are reproduced – the chipped tiling and uneven floors of palaces in kingdoms and regimes in decline (part of the point of such painting by Western-trained artists)

The period surveyed in the Russia’s Unknown Orient show stretches from 1850 to 1920 and includes earlier graphic sources, such as prints and maps. Two late eighteenth century etchings & watercolours by the German printmaker, Christian Heisler give us a sense of the elements of the style that would come to be called Orientalism, with its heightening of cultural exoticism – even before Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign (1798-1801) increased the demand for such themes. Heisler participated in the famous Peter Pallas expedition of 1793-94 to record every detail of Catherine the Great’s vast empire and especially the novelty of what were referred to as ‘the new territories’, annexed during the Russo-Turkish wars of the eighteenth century.

The show features the largest selection of the work of Vasily Vereshchagin assembled outside of Russia in more than a century. At the time of the Crimean War, Vereshchagin was a naval cadet and although his academic training in St Petersburg and in Paris under Gérôme prepared him for grandiose classical and historical themes, his most striking work is devoted to contemporary themes and events, such as his innovative Turkestan series of 1868-1870.

Vereshchagin, was astutely entrepreneurial for his time, exhibiting in England, France, Germany and the US and living for some years in Munich, but his work has not been widely seen in the West since 1902, when a series of Philippines-based works and a suite of history paintings of Napoleon’s Russian campaign were shown at the Chicago Art Institute. The Czarist Government bought the series at the time of the US show and these works were shown last year at the State Historical Museum in Moscow in the build-up to the no doubt grand and nationalistic 200th anniversary celebration of 1812 to be held next year.

It is known that Vereshchagin visited Hong Kong on his return from the Philippines, although we do not know if he created any works here. He was however especially interested in British imperial subjects and made a number of well-known studies of the Indian mutiny as well as one of the largest paintings of all time - The state entry of King Edward VII, prince of Wales, into Jaipur in 1876, currently in the Victoria Memorial in Calcutta. (The partially restored work is a huge 7metres by 5metres.)

The best collection of his work is undoubtedly in the Tretyakov Museum in Moscow – Vereshchagin had the good fortune of having Pavel Tretyakov as one of his patrons and the entire Turkestan series was acquired in 1874 and the Indian series in 1880. The great coup of this exhibition is to have secured so broad a selection of his paintings and drawings from this source.

Although Vereshchagin is a war painter, he has long been regarded as a pacifist in his depictions of the horrors of war. His iconic painting Apotheosis of War, 1871, consisting of a pyramid of human skulls, visually quotes a Christian Heisler print of the same subject– also included in the exhibition. The exhibition installation assembles a narrative emphasizing the impact of Apotheosis of War by placing it between At the Fortress Walls (1871) and Surprise Attack to focus on the barbarism of war. The Turkestan series features the rich ethnographic observation of Vereshchagin, notably in genre pieces such as Dervishes in festive clothes, Tashkent (1869) and Politicians in an Opium Den, Tashkent (1870) placed on either side of the magnificent Doors of Timur (Tamerlane) (1872-3).

Equally striking is the collection of his drawings, such as the remarkable Procession Celebrating Muharram in Shusha, 1865, depicting an ancient Shi-ite ritual involving self-flagellation and body piercing, observed in Shusha (present-day Nagorno-Karabakh, in eastern Armenia).

Vereshchagin accompanied military expeditions not just as an ‘embedded reporter’ but also as a fighting soldier and was decorated for his efforts in the Russian victory at Samarkand in 1868. He traveled widely, not only in the Caucasus and Central Asia, but also in South and East Asia – in India, Tibet, China and Japan – finally losing his life when the ship he was on struck a mine during the Russo-Japanese War in 1904.

If Vereshchagin’s extensive work is one of the highlights of the exhibition, another centerpiece is the freshly restored and exquisite tempera on canvas ‘scroll’ by Evgeny Lanseray, depicting the Peoples of Russia and of Asia. The huge, seven-metre wide work, originally a design for the proposed redevelopment of the Kazan Station – the Moscow terminus for the Trans-Caspian Railway - under the architect Aleksey Shchusev and featuring the work of a number of Mir Iskusstva (World of Art) artists also represented in this exhibition, the canvas lay hidden in the Tretyakov for 70 years prior to its rediscovery during research for this exhibition.

The exhibition includes works from collections in the Caucasus and Central Asia never previously seen in the West and revealing entirely unappreciated aspects of the development of Orientalist painting. If the forms and concerns of academic Salon painting characterize French and British Orientalism in its better-known examples, the bridge between neo-classicism and modernism is much more clearly illustrated in the visible overlaps between primitivism and Orientalism in Central Asia. Additionally, the influences of regional styles, such as Persian miniature painting are manifested in the innovative adaptations of artists such as Nikolayev, a student of Malevich who converted to Islam.

Rare photographs and prints from Russian ethnographic collections are also included in the show, giving us a dynamic sense of the dialogue between photography and painting in this period (whereas we might say that in French and British Orientalism, the dialogue is more commonly between painting and sculpture, especially in the porcelain or marble-like skin-tone of Gérôme’s female subjects).

As David Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, has suggested, no fundamental Saidian distinction between the European ‘self’ and the Asian ‘other’ is made, not only in Vereshchagin’s work but also in much of the work in this show. To quote Vereshchagin in words that still apply over a century later, ‘we often hear claims that our century is highly civilized, and that it is hard to imagine how mankind could possibly develop even further. Is not the opposite really true? Wouldn’t it be better to accept that mankind has only made the most tentative steps in all directions, and that we still live in the age of barbarism?’

The triumph of this unusually important show is that it manages to re-orient the circuits of influence that have changed 20th and 21st Century art in both the East and the West in new and fresh ways. The exhibition is supported by a well-illustrated catalogue with essays by curator Inessa Kouteinikova and scholars including Schimmelpenninck van der Oye.

Exhibition: Russia's Unknown Orient: Orientalist painting 1850-1920

Date: 19.12.2010 – 8.5.2011

Venue: Groninger Museum

Catalogue:

Russia's Unknown Orient: Orientalist painting 1850-1920. NAi Publishers, Amsterdam, 2011, 224 pages ISBN-10: 9056627627; ISBN-13: 978-9056627621.