藝評

Chris Evans and Pak Sheung-chuen: Two exhibitions – a review

楊陽 (Yang YEUNG)

at 7:22pm on 19th December 2017

Captions:

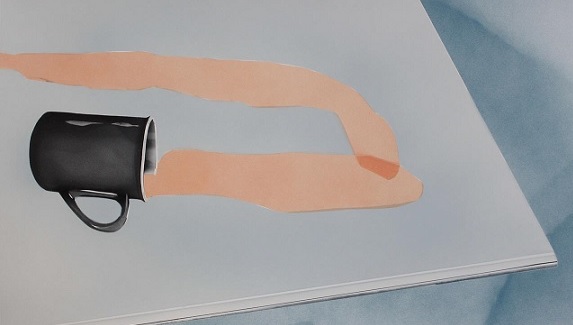

1. Chris Evans, untitled , 51 x 68 cm, airbrush painting on paper, 2017. Courtesy of the artist

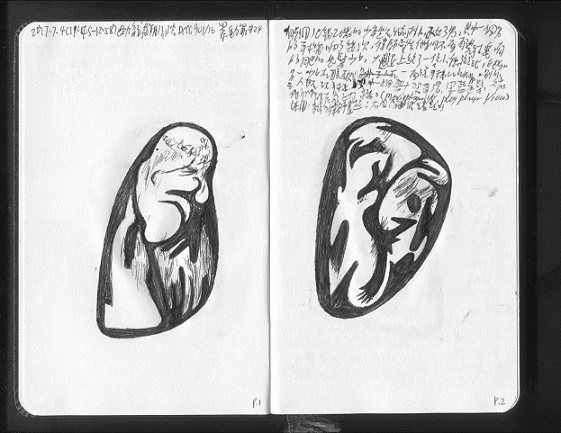

2. Pak Sheung Chuen, The seals, size variable, 2017. Courtesy of the artist

3.- 5. Installation views of the exhibition. Courtesy of Para Site

(原文以英文發表,評論〈Chris Evans、白雙全 : 雙個展〉。)

“Chris Evans and Pak Sheung-chuen: Two exhibitions” presents a challenge. Nothing dominates. Nothing asserts itself as beginning or end. Everything is moving.

Evans’ glass panels keep gliding as if on ice. They might even be floating. The blue, grey, black dabs on each panel keep crawling up (or sliding down) on the glass. Milk tea from a knocked-over mug keeps running toward one corner of the table. The hanging coat keeps hanging. Pak Sheung Chuen’s cursive script, out-of-breath, keeps chasing after its own tail, pushing the edges of the notebooks, page after page. Like insignia, the drawings hop out of graphical space to encroach upon the white walls. They keep morphing. All these are happening when the air is still dappled with Evans’ jingle that greets each body entering the gallery.

Fluidity as a state of being could be one way of reading the two exhibitions. In life, transaction windows could be anywhere – from customs and visa counters, to banks and prisons…apparatuses for the management of population as statistics and the control of human encounters as cleansed of emotions and everything else the procedures cannot handle. They could also be nowhere – by establishing themselves as transparent, their exercise of power is concealed. In the exhibition, Evans’ transaction windows loiter between fictive and social space, at once a critique and a laugh.

In Pak’s exhibition, fluidity is the quality of the artist’s mind, its muscles restlessly at work. There could be many names as to what are on display – signs, symbols, records, marks, stamps, traces…names that refer to something else as their source of meaning, that justifies their presence. I am more interested in moving away from these names, so as to think less about what they are and more about what they do in the gallery. As we follow the artist into the courtroom in which cases of those prosecuted for being involved in recent protests in Hong Kong are heard, we are drawn into the artist’s way of hearing, seeing, thinking, drawing, and more drawing that suspends thinking. We rest, as the artist does, on the particular rationality of his hand, letting it take over other rationalities at work. Pak says these automatic drawings keep leading him back to what he identifies as the established iconography of Christianity – the dove, the lamb, praying and kneeling bodies… But what if there is not one code to crack, not one origin to refer to? In a public discussion on his exhibition, I asked Pak what Jesus was in this context. “Jesus is politics,” he said. Here lies the second possibility of reading the two exhibitions: a tentative collection of objects of dissent – objects that simultaneously bring dissent upon them (when they are passive) and produce dissent (when they are active).

Evans’ Cowlick (I-V), made from cowlicks “cast from genuine licks made by cows in buckets of molasses and cereal” (as the exhibition booklet introduces) wet the tutelage of routinization. In the way they suggest both perversion and sensuousness, I think of the abject. Abjection, as Julia Kristeva analyzes, is a “dark revolt of being” that cannot be assimilated. The abject, she says, draws one towards the place there is neither object nor subject, but one where meaning collapses. Abjection in Pak takes on an air of defiance. As if encountering street graffiti, one who has no prior training in the symbolism Pak refers to may find his objects undecipherable. But be it iconography or iconoclasm or neither, for the untrained, his objects produce dissent by refusing to be content or to settle with a stable relation between symbol and meaning so that the last frontier of imagination is not up to be conquered yet. In addressing particular kinds of systematic violence that penetrates into our business of determining who we are – Evans for the soporific lethargy in transaction and transition, and Pak for the ceaseless and disturbing shifts of perception with a symbolic language in formation – the artists lead us towards a possibility of re-claiming transparency.

In the book Transparency, Marek Bieńczyk wonders how “complete transparency” is a frequent claim made by those holding positions of power in governments, administrative and economic affairs, etc. in the name of the public good. Bieńczyk asks, “Why is it that we see more and more glass in buildings? Why do we hear assurances of transparency more and more often in political speeches? Does this indicate some persistent, secret aspiration that, while hardly new, is increasingly assertive in seeking its fulfillment?” Bieńczyk notices that all institutions seeing transparency as their goal “assumes an air of finality” about the legibility and visibility of their functions, while simultaneously producing “new obscurities” and “new shadow-zones.” In comparison, an older understanding of transparency for philosophers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau is “language of the heart”, its expression “knows no shadow, nothing falls between the heart and the face, they exist in a commonness of purpose, like communicating vessels.” As Evans and Pak tap into a common but distinctly abstracted, non-linguistic reality, they address transparency instrumentalized by particular institutions, while showing that no one, no system, can claim monopoly on this quality also of the heart and mind. For instance, Evans shows the way contingency mindlessly and abruptly interrupts routines. The nature of things simply arrives unannounced and shows itself. Transparency could be discerned only until after-the-fact. Pak’s transparency is primarily in relation to himself – the laying bare of his struggle in making sense of an entangled world. Among other things, this struggle may have been nesting love – in relation to himself and others who have come into his drawings, in the serenity and lucidity of the law. In both, transparency is open-ended and reciprocal. From there, Evans and Pak lift us off the urgency of immediate realities, so that poetry could return: poetry, as Octavio Paz says, that takes upon “impartial clarity in which things become presences and coincide with themselves.” Evans and Pak follow through art and present it as the transitional, and while they are at it, also let art tell the truth.

References:

Bieńczyk, Marek. Transparency. Tr. Benjamin Paloff. Champaign: Dalkey Archive Press. 2007/2012.

Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror. An Essay on Abjection. Tr. Leon S. Roudiez. New York: Columbia University Press. 1982.

This article was first published in CoBo Social, November 2017