藝評

Paul Cézanne and the work of other artists – as viewed from the perspective of twenty-first century Hong Kong 從二十一世紀香港的角度看塞尚及其他藝術家的作品

祈大衛 (David CLARKE)

at 4:46pm on 30th January 2025

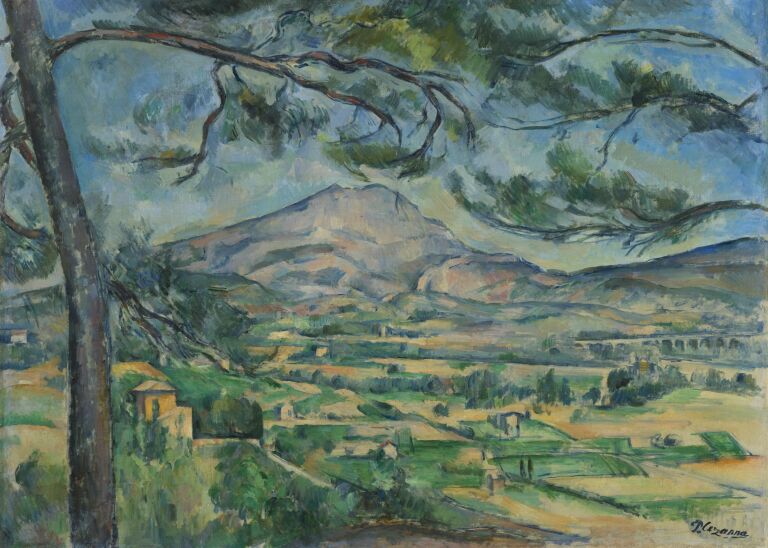

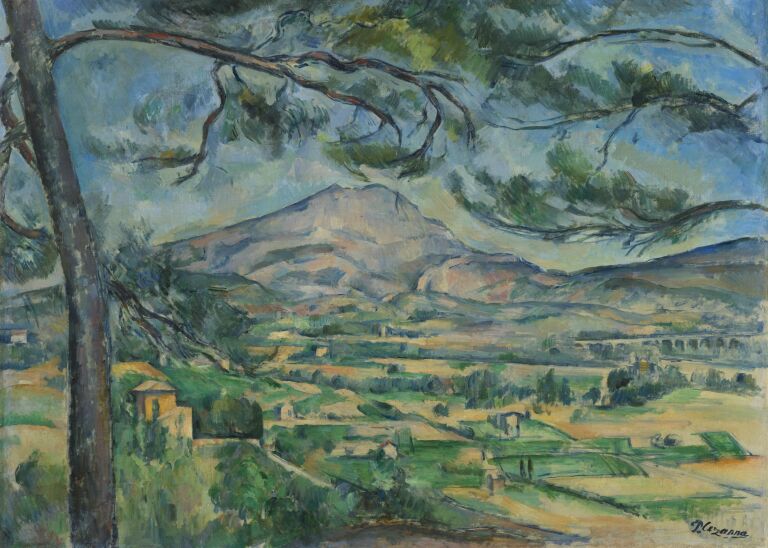

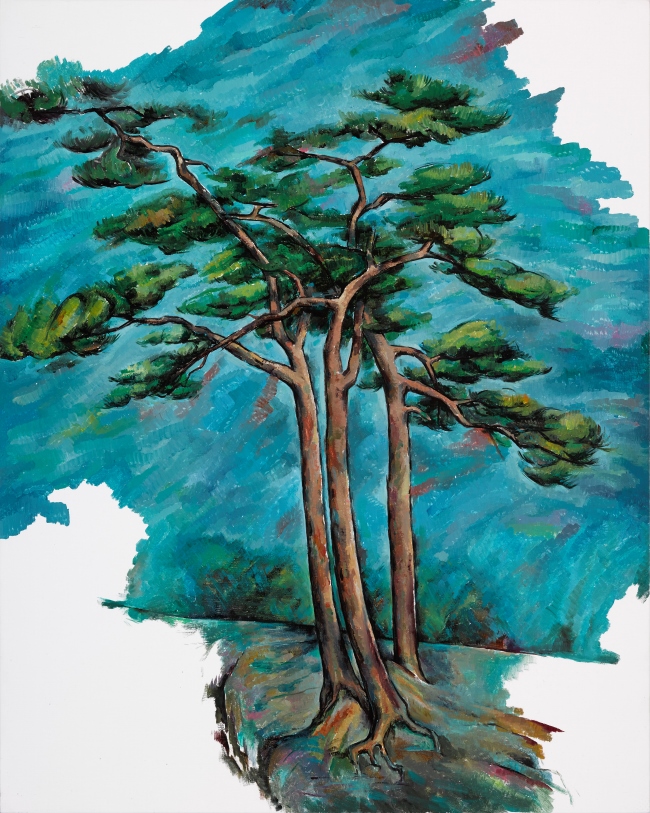

Above image: Paul Cézanne, Montagne Sainte-Victoire with Large Pine, c. 1887, Courtauld Gallery, London.

(David Clarke's long article (13,000 words) discussing the pairing of Cézanne and Renoir at a Hong Kong Museum of Art exhibition; an alternative pairing of Cézanne with Camille Pissarro; and, Chinese artists influenced by Cézanne)

Paul Cézanne and the work of other artists – as viewed from the perspective of twenty-first century Hong Kong

by David Clarke

‘Cézanne and Renoir: Looking at the World’, a major exhibition of the work of these two French artists, is on display at the Hong Kong Museum of Art from 17 January till 7 May 2025. [Plate 1] It features 52 artworks from the collections of Musée de l’Orangerie and Musée d’Orsay, two major Paris art museums. The first of these two museums is the primary source of the works on display. On the website of the Musée de l’Orangerie it is described as one of the museum’s ‘Exhibitions off-site’, and given the subtitle ‘Masterpieces from the Musée de l’Orangerie’s collections’ - indeed that same subtitle is used for the Hong Kong presentation. [1] Prior to arriving in Hong Kong it had been shown at the Palazzo Reale, Milian (19 March – 30 June 2024), and at the Fondation Gianadda, Martigny, Switzerland (29 May – 7 September 2024). Following its Hong Kong showing it will travel to the Mitsubishi Ichigokan Museum, Tokyo (29 May – 7 September 2025) and the Seoul Art Center, Seoul (20 September 2025 – 25 January 2026).

.jpg)

Plate 1: David Clarke, Signage outside the Hong Kong Museum of Art concerning an upcoming exhibition, ‘Cézanne and Renoir: Looking at the world’, featuring a detail of Cézanne’s Apples and Biscuits, 11 January 2025.

On the website of the Hong Kong Museum of Art, Cézanne and Renoir are described as ‘icons of the Impressionist art movement in France’, who ‘sought to reinvent the art of their time with their innovative depiction of the rapidly changing modern world’. It also claims that they ‘became influential figures for the new generations of painters, including Spanish master Pablo Picasso’. [2] This description of the two artists is arguably somewhat imprecise. Although Pierre-Auguste Renoir was certainly one of the main figures of French Impressionism, Paul Cézanne’s reputation is primarily based on the work he produced which moves beyond Impressionist idioms, and so to describe him as an iconic Impressionist seems rather strange. Certainly he did exhibit three paintings in the first Impressionist exhibition of 1874, and a much larger number in the third exhibition of 1877, but it is as a ‘Post-Impressionist’ he is primarily known. He was the first Post-Impressionist to develop his breakthrough idiom – both Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin were only to find their signature styles in 1888 (although the short-lived Georges Seurat – often termed a Neo-Impressionist – had his stylistic transformation a few years before that). Putting Cézanne’s name first in the exhibition title therefore seems hard to justify, given that in art historical terms he belongs to the ‘next’ generation after Renoir and the other Impressionists. It is presumably his date of birth which leads to him being offered this priority – he was born in 1839, whereas Renoir was born a couple of years later in 1841.

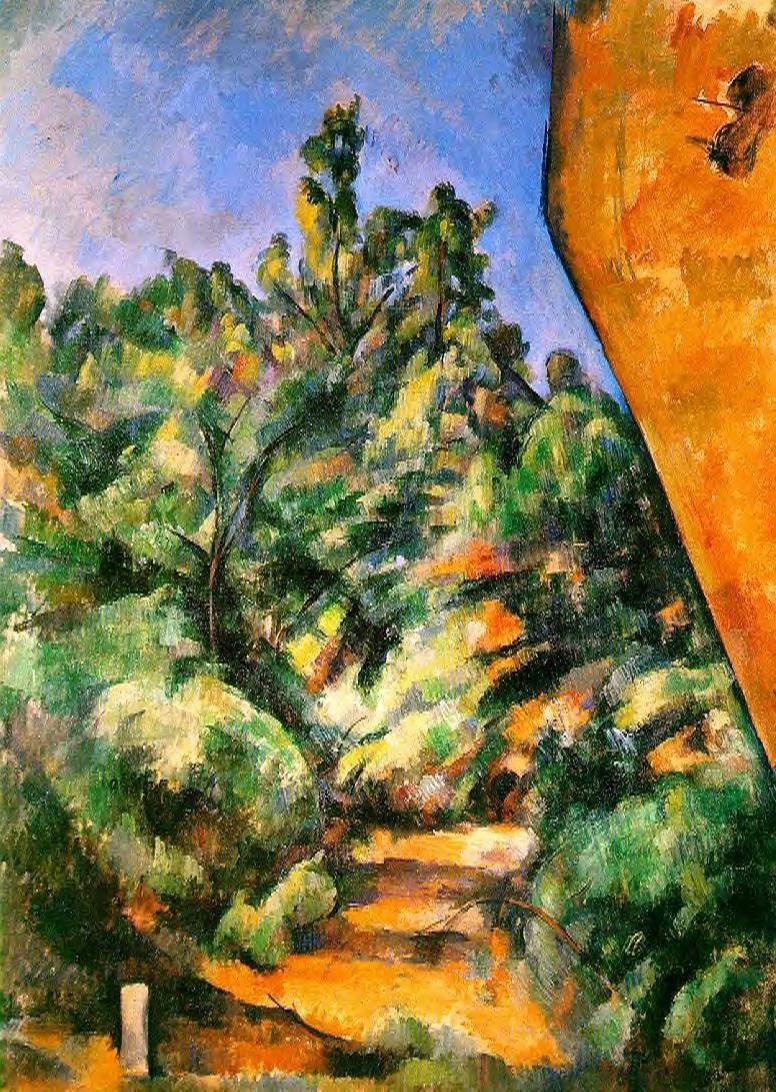

Cézanne is most well-known for his landscape paintings, particularly those produced after his return to his native Provence. It is therefore strange to describe him as someone who made innovative depictions of a ‘rapidly changing modern world’, even if Renoir (and Claude Monet too) did make contemporary Paris and its suburbs their subject in many works. Focusing on those aspects of nature which were relatively untouched by human hands and lacking in major changes over time – such as his favourite motif the Mont Sainte-Victoire [Plate 2] – Cézanne definitely does not make either the celebration or critique of modernity a focus of his art. The concern with representing fugitive light and atmospheric effects - which was so central to the Impressionist art of Renoir and Monet (but not that of the equally significant Impressionist artist Edgar Degas) – is also not found in Cézanne’s later painting. Part of what he liked about the southern French landscape with which he was so familiar was its relative stability over the seasons – ‘the vegetation doesn’t change here’ he wrote to Pissarro in July 1876, ‘the olive and pine trees always keep their leaves’. [3] Similarly, the rocks featured in many of his paintings are an aspect of nature that is obviously not subject to seasonal alteration (or any other noticeable change over the time he would be observing them). The Red Rock (c. 1895-1900) and On the Grounds of the Chȃteau Noir (1898-1900) are two works featured in the exhibition in which rocks are a prominent subject, both being from the Musée de l’Orangerie collection [Plate 3]. The many paintings he made in the Bibémus quarry not far from his home, such as Bibémus Quarry (Carrière de Bibémus), (c. 1895, in the collection of the Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia) are also evidence of his concern with the solid forms of rock rather than with fugitive atmospheric effects. [Plate 4]

Plate 2: David Clarke, Mont Sainte-Victoire, viewed from Les Lauves, Aix-en-Provence, France, 12 May 2006.

Plate 3: Paul Cézanne, The Red Rock, c. 1895 – 1900, Oil on canvas, 92 x 68 cm, Musée de l'Orangerie. © GrandPalaisRmn (musée de l'Orangerie) / Hervé Lewandowski.

Plate 4: David Clarke, Bibémus quarry, Provence, France, 11 May 2006.

When poor weather prevented him from getting out into the landscape to work Cézanne would often turn his attention to still life painting. Apples and other such objects seen in his still life paintings are no more ‘modern’ than the trees and rocks of his landscape works. Similarly, the breakthrough to a signature Post-Impressionist idiom of both Van Gogh and Gauguin occurred after they had left Paris (to Arles and Brittany respectively), and didn’t involve an engagement with modern life subject matter. [4]

Certainly Cézanne was deeply influential on Picasso (although the word ‘influence’ itself misrepresents the process at work since it is always the artist being ‘influenced’ who is the active partner, appropriating and often creatively misunderstanding the earlier artist). It would be impossible to imagine Cubism coming into being without Picasso’s dialogue with the art of this predecessor. It was the encounter with Cézanne’s art around 1906 (the year of that artist’s death) which helped Picasso move beyond the idiom of his blue and rose periods towards something radically different. His Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (The Young Ladies of Avignon) of 1907 could not have been created without the precedent of Cézanne’s many paintings depicting groups of female bathers. That breakthrough work does also show Picasso looking at African sculpture for inspiration concerning new artistic directions, but it was the legacy of Cézanne which was to prove central in the art he went on to produce in subsequent years.

During that period of Cubism’s gestation Picasso was in a close artistic dialogue with Georges Braque (the co-creator of that stylistic idiom), and it was perhaps Braque’s own interest in Cézanne at that time which helped Picasso realize the central significance of that artist’s work to what they were doing. Braque had painted his Houses at L’Estaque in 1908, producing in response to Cézanne’s art (and at a location that artist had himself worked) what might be considered the first Cubist landscape painting. With this work Braque definitively abandons the coloristic Fauve manner he was working in just a couple of years earlier in favour of a concern with simplified form. Picasso produced Factory at Horta de Ebro (also referred to as Brick factory at Tortosa) in the following year, and since landscape was not a significant aspect of his artistic output as a whole he is surely responding in this work to Braque’s innovative engagement with Cézanne’s landscape work. Looking back on Cézanne from the perspective of 1941, Picasso referred to him as ‘my one and only master!’, confessing that he had spent years studying that artist’s pictures, ‘It was the same with all of us – he was like our father’. [5]

Henri Matisse had developed his interest in Cézanne at an earlier date than either Picasso or Braque, having purchased that artist’s Three Bathers of 1879-1882 in 1899. In 1936 he claimed that particular painting had ‘sustained me spiritually in the critical moments of my career as an artist; I have drawn from it my faith and my perseverance’. [6] At a still earlier period Gauguin had purchased Cézanne’s Still life with Compotier of 1879-1880. He even represents this still life painting of a fruit bowl in the background of one of his own portraits, an 1890 study of a female figure which echoes the pose in which Cézanne painted his wife in a work of earlier date. Cézanne’s Still life with Compotier also appears in Maurice Denis’s painting Homage to Cézanne (1900), which shows a group of artists gathered around it, including (besides Denis himself) Emile Bernard, Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard and Odilon Redon. Although Gauguin’s 1890 painting is likely to have been the first occasion an artist engaged with one of Cézanne’s portraits of his wife in their own work, it was not the last. In 1962 Roy Lichtenstein painted Portrait of Madame Cézanne, not a direct representation of the original work (an 1885-1887 painting from the Barnes Foundation collection in Philadelphia) but a response to a diagram purporting to explain its compositional structure that appeared in a book of 1943 by art historian Erle Loran. Paul Klee saw eight paintings by Cézanne at the Munich Secession in 1909, and responded with the comment: ‘this is the teacher par excellence’. [7]

Clearly Cézanne’s influence on the art of the subsequent generation was widespread. It was also geographically broad, in that even Japanese painter Yasui Sōtarō (who was in France from 1907 till 1915) was deeply admiring of Cézanne. However the Hong Kong Museum of Art’s claim on its website that both of the artists in the show were influential on subsequent art is hard to sustain since it would be difficult to find anything like the same influence being exercised by the art of Renoir. So much of art following Impressionism was a reaction against it, so this is perhaps to be expected. Both Matisse and Picasso did admire Renoir’s painting (and Picasso did own some paintings by Renoir), but it would be impossible to argue that Renoir had an impact on their art that was of equivalent significance to that which can be easily traced in the case of Cézanne.

Even the pairing of Cézanne and Renoir in the exhibition seems a little strange. Certainly the artists were friends but it might be hard to argue that there was a strong creative interaction between them, given the difference of their styles. Renoir introduced a collector of his art, Victor Chocquet, to Cézanne, and Chocquet was to become a big supporter of that artist too. Cézanne painted Chocquet’s portrait more than once, but his interpretation was quite different from that which Renoir made when he represented the collector. Renoir visited Cézanne in Provence in 1882, returning there on several later occasions too. Cézanne visited Renoir in La Roche-Guyon in 1885. Renoir made several significant multi-figure modern life paintings during his Impressionist heyday, perhaps most famously his Bal du moulin de la Galette (commonly known as Dance at Le moulin de la Galette) of 1876, but there is no real equivalent in Cézanne’s output. While Renoir was responsible for commissioned portraits such as his Mme. Charpentier and her children of 1878, Cézanne tended to find sitters for his figure paintings amongst his personal acquaintances. Both artists painted their family members, though, and this exhibition features both Renoir’s portrait of his son (Claude Renoir in Clown Costume, 1909) and Cézanne’s The Artist’s Son of c. 1880 [Plates 5 and 6]. On a visit to his friend in Aix during 1889 where the two artists worked together outdoors, Renoir painted Mont Sainte-Victoire, the motif so strongly associated with Cézanne. Renoir focuses on atmospheric effects, however, rather than on creating a unified pictorial structure linking foreground and distant forms into a whole as Cézanne does in such canvases of the motif as the one in the collection of the Courtauld Gallery in London - Montagne Sainte-Victoire with Large Pine of c. 1887 [Plate 7].

Plate 5: Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Claude Renoir in Clown Costume, 1909 Oil on canvas, 120 x 77 cm, Musée de l'Orangerie. © GrandPalaisRmn (musée de l'Orangerie).

Plate 6: Paul Cézanne, The Artist's Son, c. 1880, Oil on canvas, 35 x 38 cm, Musée de l'Orangerie. © GrandPalaisRmn (musée de l'Orangerie) / Hervé Lewandowski.

Plate 7: Paul Cézanne, Montagne Sainte-Victoire with Large Pine, c. 1887, Courtauld Gallery, London.

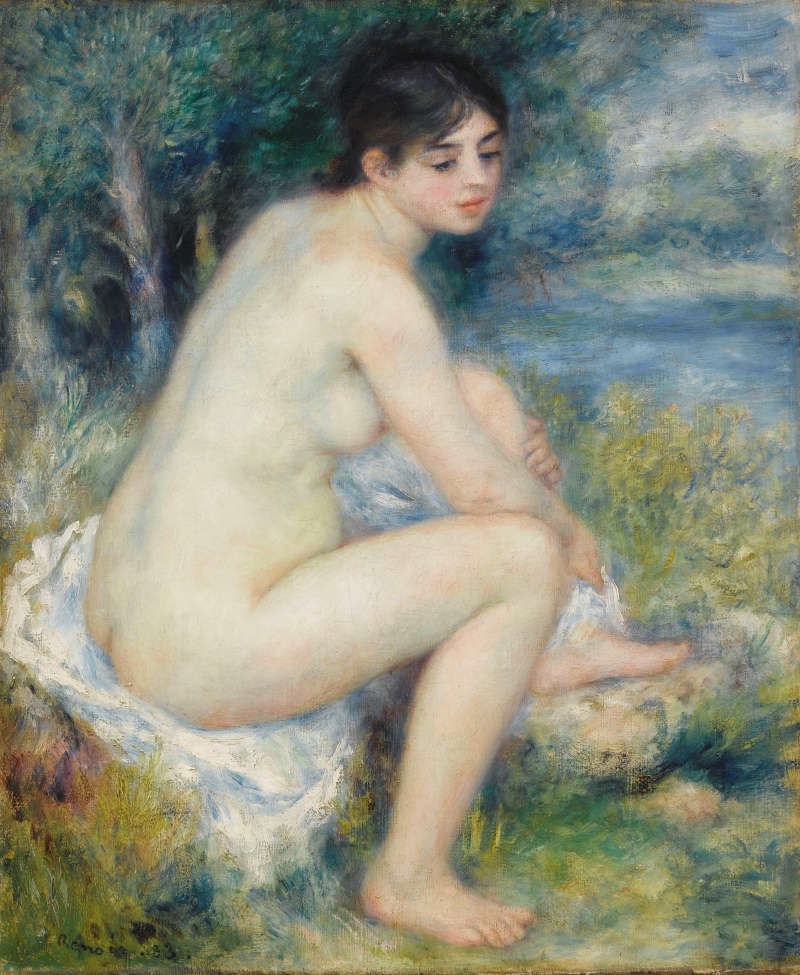

Perhaps the strongest parallel between Renoir and Cézanne can be found with the theme of female bathers. Some of the publicity material the Hong Kong Museum of Art has used for ‘Cézanne and Renoir: Looking at the World’ has included details of their paintings of female bathers, so they clearly are aware that this is a theme on which the two artists converge. [Plates 8 and 9] Works by both artists featuring bathers are included in the exhibition, including Cézanne’s Three Bathers (of 1874-5, from the Musée d’Orsay collection) and Renoir’s Nude in a Landscape (of 1883, from the Musée de l’Orangerie collection) [Plates 10 and 11].

.jpg)

Plate 8: David Clarke, Announcement in the Hong Kong Museum of Art concerning an upcoming exhibition, ‘Cézanne and Renoir: Looking at the world’, 11 January 2025.

.jpg)

Plate 9: David Clarke, Publicity near the Hong Kong Cultural Centre concerning an upcoming exhibition at the Hong Kong Museum of Art, ‘Cézanne and Renoir: Looking at the world’, 11 January 2025.

Plate 10: Paul Cézanne, Three Bathers, 1874 – 1875, Oil on canvas, 19.5 x 22.5 cm, Musée d'Orsay. © GrandPalaisRmn (musée d'Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski.

Plate 11: Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Nude in a Landscape, 1883, Oil on canvas, 65 x 54 cm, Musée de l'Orangerie. © GrandPalaisRmn (musée de l'Orangerie).

Renoir’s treatment of the subject of bathers belongs to a relatively late phase of his work when he was moving away from his Impressionist idiom and engaging more deeply with earlier art. Veronese, Tiepolo, Raphael and Boucher are amongst the old masters that he came to admire in that phase of his life, and one can also note an appreciation of Ingres. This new direction in Renoir’s art (which occurred subsequent to an 1881 trip to Italy) can be seen in his Les Grandes Baigneuses (or The Large Bathers), painted between 1884 and 1887.

The erotic interest in the naked female body which Renoir displays in Les Grandes Baigneuses has no parallel in Cézanne’s treatment of the bathing theme, which had preoccupied him from quite an early phase in his painting career. While Renoir was solely concerned with female bathers, Cézanne also makes representations of groups of male bathers, such as his Five Bathers of 1876-7, which is included in the Hong Kong Museum of Art exhibition. Cézanne’s interest in the theme had a culmination in several works of major ambition produced during the 1890s and into the first decade of the twentieth century. The Philadelphia Museum of Art has one painted between 1898 and 1905, for instance, and the National Gallery London has one which can be dated 1894-1905. In both these works the most prominent naked female figures tend to be depicted sideways on (or even with their back to us), thus refusing an easy submission to an eroticized gaze. In any case the reduction to simplified forms in these late period canvases takes our attention away from flesh and the surface of skin – the Philadelphia work has a particularly strong triangular or pyramidal structure.

If there is an old master who influenced Cézanne’s later work in would be Poussin, whom he said he would like to do again after nature, and not any of the painters Renoir looked to in the 1880s and after. [8] Roy Lichtenstein’s 1962 response to Cézanne is not the only one by an American artist working in the second half of the twentieth century, since Jasper Johns produced six ink on plastic Tracings after Cézanne works in 1994. These were a response to that artist’s The Large Bathers of 1895-1906 in the collection of the Barnes Foundation.

If I were personally to curate a show in which Cézanne was paired with an Impressionist painter, the one I would choose would be Camille Pissarro. My only reservation about doing so would be that this has already been successfully achieved on a previous occasion. The relationship between Pissarro and Cézanne was explored in the exhibition Pioneering Modern Painting: Cézanne and Pissarro, curated by Pissarro’s great-grandson, Joachim Pissarro (Museum of Modern Art, New York, 26 June – 12 September 2005; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 20 October 2005 – 16 January 2006; Musée d'Orsay, Paris, 28 February – 28 May 2006).

Like Cézanne himself (and somewhat unlike Renoir and Monet during their Impressionist period) Pissarro had a deep engagement with the countryside. [9] While we often think of Impressionism as engaged with the representation of modern urban life, Pissarro is a bridge from the rural emphasis of Realist artists such as Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet to the somewhat similar tendency in Post-Impressionism in general. Right till the end of his relatively short life Van Gogh retained an engagement with Millet’s art, for instance, making a version after a Millet reaper image in September 1889.

Quite apart from this general shared emphasis on life outside the metropolis one can point to the close friendship between the two artists. Cézanne had met Pissarro as early as 1861, on his first ever visit to Paris. They became acquainted with each other at the Académie Suisse, where artists received no formal tuition but could work from a live model for a modest fee. It was through Pissarro that Cézanne was to meet Renoir. A close interaction between the two artists occurred when Cézanne relocated to Pontoise (where Pissarro was already based) in Autumn 1872. Before long he moved to the nearby village of Auvers, staying there till Spring 1874. Drawn portraits they made of each other survive from this time, and Pissarro also produced a more considered work in oil, his Portrait of Paul Cézanne of 1874.

Pissarro, who for art historian Richard Verdi was the ‘greatest teacher’ amongst the Impressionists, seems to have greatly influenced Cézanne during this period of proximity. [10] He would have been responsible for encouraging his friend to work directly from nature - en plein air - and to employ a looser brushwork and a more varied palette. Even at the beginning of this time of closeness Pissarro was optimistic about what Cézanne might be able to achieve. Writing to fellow artist Antoine Guillemet in September 1872 he states: ‘Our friend, Cézanne, raises our expectations, and I have seen and have at home a painting of remarkable vigour and power. If, as I hope, he stays some time in Auvers, where he is going to live, he will astonish a lot of artists who were too hasty in condemning him’. [11] In a letter to his son Lucien written in November 1895, Pissarro looks back on the time the two of them spent together in the 1870s, pointing out that there are landscapes of Auvers and Pontoise in a major show of Cézanne’s art which was then taking place at the gallery of Ambroise Vollard ‘that are similar to mine’. ‘Naturally [he adds], we were always together!’ In the same letter he admits the artistic exchange between them was in fact a two-way affair: ‘he was influenced by me at Pontoise, and I by him’. [12] In 1905, towards the end of his life, Cézanne was to make reference to ‘the humble and colossal Pissarro’. [13] At the time of the Dreyfus affair (when a Jewish military officer was falsely accused of treason), Cézanne let himself be described in an exhibition catalogue as a ‘pupil of Pissarro’, whereas anti-Dreyfusards (and anti-Semites) Degas and Renoir were cutting off ties with that Jewish artist. [14] In a letter to his friend the novelist Émile Zola of 20 May 1881 (from Pontoise) Cézanne mentions that he sees Pissarro fairly often, and their closeness continued despite an almost complete absence of face-to-face contact in the last twenty years of Pissarro’s life, which ended in 1903. [15]

Although Cézanne had already shown an Impressionist-like interest in depicting seasonal weather conditions in his Melting Snow at L’Estaque of 1870-1871 (a sharp change from the way of depicting landscape he was adopting only a short time earlier in his The Railway Cutting of 1869-1870), while at Auvers he was to produce an even more ‘Impressionist’ work, The House of the Hanged Man of 1873. This was one of the three paintings Cézanne showed in the first Impressionist exhibition of 1874, where it was actually to find a buyer, a rare occurrence for him at that time. This work shares the Impressionist concern with light and with broken brushwork. It also shows a clear abandonment of tonal thinking, and thus contrasts sharply with slightly earlier works such as his Still Life with a Black Clock of c. 1869-70. That still life painting is built around a sharp tonal contrast between the black of the clock’s body and the white of its dial and of the prominent table-cloth beneath it - which nevertheless has a sharp black vertical accent of shadow. Perhaps The House of the Hanged Man is as close as Cézanne ever comes to embracing the Impressionist vision, although his Auvers, Panoramic View (1873-1875) is also worth mentioning.

It is possible to document Cézanne’s desire to learn from Pissarro in the early 1870s by observing that he was to make a direct copy around 1872 of one of Pissarro’s landscapes of 1871, Louveciennes. [16] This would be a question of studying Pissarro’s brushwork, rather than of appropriating his methods of working from the motif. The copying of the painting would not have involved any outdoor work, obviously, and would have taken place in a location far removed from that place on the outskirts of Paris which Sisley, Renoir and Monet also depicted (and to which Pissarro had moved in Spring 1869). Clearly, though, Cézanne did go on to work out of doors in Pissarro’s manner, and there are paintings by him which address almost identical motifs to Pissarro. His The Road to Pontoise of c. 1875 (in the collection of the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow) closely resembles in its motif and viewpoint a Pissarro work of 1875 (in a private collection, but on long term loan to the Kunstmuseum Basel in Switzerland). [17]

Cézanne’s respect for Pissarro is indirectly expressed by his inclusion of one of that artist’s paintings in the background of his Still Life with Soup Tureen (c. 1877), a work from the Musée d’Orsay collection that is featured in ‘Cézanne and Renoir: Looking at the World’. [Plate 12] The Pissarro painting in question is Rue de Gisors, The House of Father Gallien of 1873. The fact that Cézanne has included his mentor’s painting in one of his own is mentioned in the exhibition wall text for that work, which also acknowledges that his artistic style was influenced by Pissarro. Somewhat curiously that painting and its associated text comes right at the very start of the exhibition, in a section entitled ‘Viewing in Parallel’, which is devoted to exploring parallels between Cézanne and Renoir. Whilst pointing towards Pissarro rather than Renoir as the true parallel artist may be taken as undermining that section’s explicit aim, in fact the wall text introducing that section (which asserts that there are ‘numerous crossing points’ between Cézanne and Renoir’s art), does itself go on to state that ‘the geometrical shapes in the scenes of nature and bodies of Cézanne are clearly different from the pearly softness of the young women and objects in Renoir’s paintings’. [18]

Plate 12: Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Soup Tureen, c. 1877, Oil on canvas, 65 x 81.5 cm, Musée d'Orsay, Bequest of Auguste Pellerin, 1929. © GrandPalaisRmn (musée d'Orsay) / Patrice Schmidt.

When Cézanne and Pissarro painted the same motif there can nevertheless be marked differences in their treatment of it, indicating that even in that time of close dialogue Cézanne retained a separate artistic personality. His Small Houses in Pontoise of c. 1873-1874 recalls a painting by Pissarro of 1874 depicting the same houses and the hillside behind them (The Potato Harvest, Pontoise). Pissarro views the scene from further away, however, allowing him to include a foreground field with a group of human figures engaged in gathering a crop of potatoes (a subject he also represents in other works). [19] That human interest links his work more closely to the precedent of the Realist artist Millet, who treated a similar scene in his The Potato Harvest of 1855. In Cézanne’s painting the trees are only just discernible in front of the houses, whereas in the other artists’ work they occupy the foreground. Because the hills behind deny us any view towards a distant horizon Cézanne’s canvas has more of a two-dimensional feel than Pissarro’s, and the brushwork is more prominent as brushwork. Both artists pick up horizontals in the forms of the hills and the cultivation on them, but Cézanne also places a sequence of prominent near-vertical brushstrokes about half way up on the right hand side of his canvas. Although presumably representing rows of crops on the hillside, these strokes stand out as marks on a two-dimensional surface first and foremost, and only secondarily (and loosely) perform any descriptive function.

Discussing Cézanne’s relationship with Pissarro has diverted my discussion from being a straightforward review of ‘Cézanne and Renoir: Looking at the World’, and indeed I had already had reason to mention several works not included in the exhibition prior to that point. I therefore feel it is not inappropriate if I now go on to discuss one of my favourites amongst Cézanne’s later works which is also not included in that exhibition. This can serve as a supplement to the first-hand engagement with his work which ‘Cézanne and Renoir: Looking at the World’ provides to those in a position to view it, and hopefully help to present a broader picture of his art than the works selected for the exhibition are able to offer by themselves. The painting I am choosing to analyze is Still Life with Plaster Cupid, a work of c. 1894 which is oil on paper, mounted on board, and in the collection of the Courtauld Gallery, London. [Plate 13]

Plate 13: Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Plaster Cupid, c. 1894, Courtauld Gallery, London.

Plate 14: Paul Cézanne, Apples and Biscuits, c. 1880, Oil on canvas, 45 x 55 cm, Musée de l'Orangerie. © GrandPalaisRmn (musée de l'Orangerie) / Hervé Lewandowski.

In this work the artist gives us a sense of three-dimensional space, and indeed a much larger sense of space than that found in many of his other still life paintings (such as Apples and Biscuits of c. 1880, featured in the exhibition), or indeed in much still life painting by other artists. [Plate 14] But at the same time he is clearly also interested in two-dimensional design, in the placement and linkage of forms across the painting surface – and has been willing to depart from the conventions of perspective to achieve this. Of course in still life painting there is an advantage not present in landscape or portraiture in that one can arrange the objects to be painted just as one wishes, to create appropriate formal organization (whereas one cannot move a tree or reshape a nose), but Cézanne goes well beyond that. The angle at which we are looking at the floor is quite different from that which we have on the table top, for instance. Clearly this eliminates a spatial ‘hole’ in the painting, helping to bring forms together across the surface. The two sides of the canvas stacked against the wall behind the plaster statue are similarly seen from slightly different viewpoints – is would be hard to imagine the top and bottom edges actually meeting up. One can suggest that this fragmentation of the represented canvas has been done to ensure that the straight lines of its edges can contrast more tellingly with the curved forms emphasized in the hair and body of the cupid (objects at different spatial depths can nevertheless be adjacent visually). This sequence of curved forms in the represented sculpture is allowed to continue down the painting’s surface because the artist has placed a row of apples just below the foot of the cupid which extends it beyond the body itself. The two onions on the table also help create formal interest – the one to the right breaks the form of the table edge there, as does the one to the left (although in that case the green sprout of the onion begins just as it passes in front of the edge of the canvas behind, not coincidentally of course). The apple seen at the deepest point of the space behind seems as large as the ones in the foreground – rather than being diminished by distance it retains the size it needs to be in dialogue with the other circular forms across the painting’s surface.

One visual linking of forms in different spatial planes is that provided by the blue cloth. It appears under the plate on the foreground table, but is also seen further back in space on the left hand side. Although this looks at first glance like a continuation of the same cloth, in fact that may be a representation of the cloth on a painted surface (and the apples on it may be painted apples, not ‘real’ ones like those on the table in the foreground). The attention to the two-dimensional arrangement of forms on the surface makes us aware that we are looking at a painting as a painting, but also at the level of subject matter itself art is here made visible. Whereas many still life paintings are set in kitchen environments or even just anonymous generic spaces, Still Life with Plaster Cupid is instead set in an artist’s studio. In this painting we see both a sculpture (the cupid) and at least two paintings (several other canvases are visible but since they are turned away from us we don’t know for sure if there is paint on them yet). The painting with blue cloth and apples may in fact be identifiable as a specific known work, The Peppermint Bottle (1893-5, in the collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.). [Plate 15] In addition there is a painting further back in the studio space which appears to represent a sculpture of a ‘flayed man’. Such sculptures present the human body with skin peeled away, and were commonly utilized in art schools to aid students in their understanding of musculature. So in addition to a sculpture we also have a painting of a sculpture as well. Of course all these paintings and sculptures only exist within a painting, but just as The Peppermint Bottle actually exists in the real world, so does the plaster cupid. This small sculpture was in Cézanne’s own possession, and can be seen by visitors to his studio (which was preserved after his death, and is now open to the public) along with various other objects that we know from their appearance in his paintings, such as the fruit bowl (which in actual fact doesn’t have the elongated shape that it is given in Still life with Compotier). Although the shadow half way down the thigh in Still Life with Plaster Cupid might seem to be something that the artist has invented to help create a further curved form in the body in fact there is (perhaps surprisingly) such a shape to the thigh of the sculpture itself.

Plate 15: Paul Cézanne, The Peppermint Bottle, 1893-5, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

I have been arguing here that ‘art’ is a subject of this painting - that it is art about art - but one can also argue that there are two other subjects being treated here: death and love (possibly the two biggest topics that art can address). Death comes in through the image of a flayed man (to be deprived of one’s skin would certainly prove fatal), and of course love is there because Cupid (who appears extremely frequently in European art) is the god of desire, of erotic love, in classical mythology. Certainly both death and love are only obliquely present, but that is without doubt deliberate. These are both subjects that appeared in Cézanne’s early work in a very raw and direct way. The Abduction of 1867 presumably treats a theme of rape from classical mythology, while The Murder of 1867-1870 (in the collection of the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool) is an image of extreme violence. As the art historian Meyer Schapiro has argued, Cézanne’s later work may involve an attempt to transcend the raw emotion of his early work, on which the Romantic artist Eugène Delacroix was a major influence, finding a more mediated manner of expression rather than altogether abandoning earlier themes [20]. The late works are not just about purely formal issues, then, but are involved with issues of meaning (as all great art is). [21]

Since ‘Cézanne and Renoir: Looking at the World’ is a twenty-first century exhibition taking place in Asia (in addition to its earlier tour around European locations), the question naturally arises what meaning his art might have for such a time and place, far removed as it is from those in which it was made. To address this question - partially, at least - the approach taken here will be to look briefly at how recent Chinese artists have responded to Cézanne, an artist whose works have not for the most part been widely seen in their home country. When discussing this artist’s ‘influence’ I mostly focused on the generation following on from him, although we have also noted reference to his work by Lichtenstein and Johns. By now going on to examine how artists from a very different part of the world to Cézanne are still engaging with his work in recent moments I hope to demonstrate that he remains a living force for his fellow artists even today.

Discussion of Chinese and other non-Western art of the last century has sometimes presented it as engaged in mimicry of Western modes or as catching up with a process of artistic modernization specific to the West. [22] In reality, though, cultural modernity existed in diverse forms all around the globe, and engagement by Chinese artists with Western art from the early twentieth century onwards has always been a selective matter, concerned with adapting what might be of use in the local context. Whilst artistic modernism in Europe was tied up with the project of overthrowing illusionistic realism of the kind that had been dominant there since the Renaissance, no such task was central in China since ink painting of earlier eras in that country had never prioritized mimetic goals, and Chinese aesthetic theory drew attention to brushwork as the trace of the maker’s hand. Cubist art, therefore, never had a big influence in China. Due to the relative cultural closure of the People’s Republic during the Maoist era it was only during a later 1980s moment of opening up to the world that Mainland Chinese artists renewed the dialogue with Western modernism that had begun during the earlier half of the century. Western modernism became known to Chinese artists (and art students) of that era all in one go, as it were. Artists in Taiwan and Hong Kong had already engaged in a significant dialogue with Abstract Expressionism prior to that point, but it was often Dada, Surrealism or Pop art which was of greatest interest to Mainland artists of the 1980s and early 1990s. [23]

Amongst the artists of that era, although certainly not one of the most prominent of them, is Li Chao (b. 1962). Although there are many other more well-known ‘New Wave’ Chinese artists of the 1980s who could be discussed to demonstrate how self-consciously and confidently Mainlanders engaged with Western art, Li is the most relevant to our present topic in that he explicitly addresses the work of Cézanne. [24] Li’s painting (in gouache on paper) was I Don’t Want to Play Cards with Cézanne of 1988. It obtained a certain prominence from being included in one of the earliest Western survey exhibitions of contemporary Chinese art, held at the Pacific Art Museum in Pasadena, California, in 1991. It was further highlighted on that occasion in that the exhibition itself took its title from that of this particular painting. [25] Clearly, as the title tells us, this is no straightforward homage to an artist the painter was influenced by, but a work that is clearly aware of the dangers of cultural deracination and loss of identity that could result from an unsophisticated and submissive engagement with a valorized foreign exemplar. In an essay in the exhibition catalogue, Richard E. Strassberg sees Li as responding in this painting to a perceived dilemma of Chinese artists of that time concerning how to employ Western artistic sources: ‘In his own words, Li is seeking a “spiritual perch” amidst the complexity of life and views art as symbolic creation which signifies the mystery and ambiguity of existence’. [26]

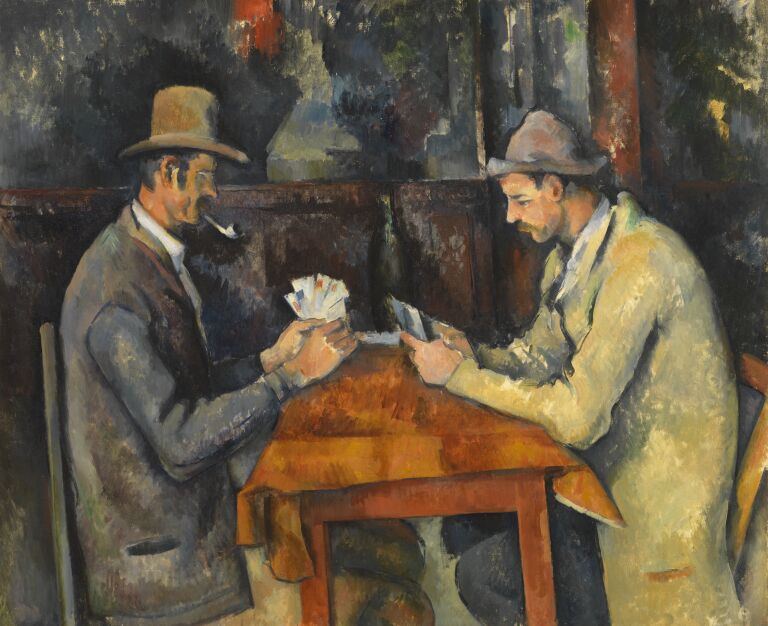

Plate 16: Paul Cézanne, The Card Players, 1892-96, Courtauld Gallery, London.

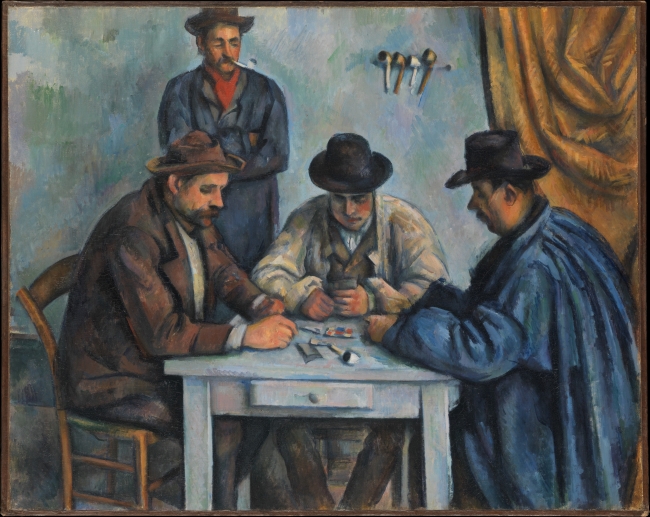

Plate 17: Paul Cézanne, The Card Players, 1890-92, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Li apparently only knew Cézanne’s art at that time through reproduction – unsurprisingly. The particular image he chose to engage with was from a sequence of five oil paintings that artist produced during the 1890s depicting peasant men at a table playing cards. [27] Li selected the painting of this theme that is in the Courtauld Gallery, London, The Card Players of 1892-96. [Plate 16] Like the version of this theme in the collection of the Musée d'Orsay in Paris (which may perhaps be the final one completed) the Courtauld Gallery painting only features two figures, facing each other on opposite sides of a table. The Metropolitan Museum (1890-92) and Barnes Collection versions have a larger number of figures. [Plate 17] Both feature three card players, with the third being a figure sitting directly opposite us (although looking down at the game as the other participants are), but they also represent spectators. In each case there is a standing spectator behind the seated figure on the painting’s left, but in the Barnes Foundation work there is also a seated spectator - a boy - between the centre and right hand players. It seems likely that Cézanne chose to simplify and concentrate the composition as he continued working on the card players theme, not only eliminating the spectators and the third player but also a rack of pipes seen on the wall behind and a hanging cloth in front of that represented surface. By reducing the players to two in the Musée d’Orsay and Courtauld Gallery versions he introduces a degree of symmetrical balance to the composition that is absent in the Barnes Foundation and Metropolitan Museum versions, and these two works also have a shallower space – the table is closer to us. While enhancing symmetry Cézanne also then finds ways to subtly undermine it at the same time. The two men facing each other in the Courtauld Gallery version both wear hats, but only one is a top hat, and whereas one hat (on the left hand figure) has a downward-turning brim, the other has an upward-turning one. Only one man is smoking a pipe, and the colour (and tonality) of their clothing contrasts markedly.

The compositional balance which Cézanne achieves in the Courtauld Gallery version of his card players theme (and the subtle nuances which he then introduces to complicate or qualify the image’s symmetry) are not present in Li’s painting. Symmetry is deliberately abandoned, with the right hand figure partially disappearing out of the painting’s space at the image’s edge. That figure has an active pose, and is not sitting at the table at all. It is also not hatted, unlike the other one. We might not be altogether over-reading the image to say that this right hand figure embodies the idea of not wanting to play cards which is given in the painting’s title. Given that title, we might also want to identify the other figure who is at the table with the cards as a sort of stand in for Cézanne himself, making the work a metaphorical representation of the ambivalence towards Western artistic sources the artist may himself have been feeling.

Such a represented ambivalence towards Western artistic sources can also be found in the work of Wang Guangyi during the same decade. Wang engages with an iconic work of the French neoclassical painter Jacques-Louis David in his The Death of Marat of 1986, for instance. He undermines David’s well known painting of that title by translating it into the grisaille idiom he was favouring at that time, and doubles the figure, thereby introducing an uncanny feel and a certain degree of abstraction. [28] This ironic, distanced approach to David contrasts sharply with the more direct and uncomplicated appreciation of that artist’s work by Xu Beihong in the earlier part of the twentieth century. Xu spent time in Europe, and so had the opportunity during a formative period to see David’s paintings themselves, rather than merely interacting with reproductions of them as Wang was doing. Wang and Li’s engagement with European artists via images in books belongs to the much wider phenomenon of ‘reading fever’ which was a major feature of Mainland Chinese intellectual and cultural life of the 1980s – following institution of the post-Maoist ‘open door’ economic policy there was a flood of new knowledge entering the country in written form. Wang told me in a 1993 interview that during his period as an art student in the early 1980s he found it easy to access information about Western art in his college library. At that time he took a particular interest in European art of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The two artists that were particularly important to him were Cézanne and Marcel Duchamp. Cézanne’s still life paintings were particularly mentioned. [29] This ‘bookish’ nature of the Chinese take on Western art during the 1980s was addressed by Huang Yong Ping in his 1987 work, A History of Chinese Painting and a Concise History of Modern Painting Washed in a Washing Machine for Two Minutes. A deliberately over-literal bringing together of Chinese and Western art is offered by this piece, with the meeting of cultures (in the form of books) proving mutually destructive rather than leading to meaningful novelty.

Li consciously departs from Cézanne’s original card players painting in his work, and I believe we cannot understand it unless we are aware of those refusals of the original, are making a sort of mental comparison to it as we view his painting. As well as the treatment of the ‘escaping’ right hand figure, which is crucial to my reading of his work as thematizing refusal of Cézanne as a model to be faithfully followed, there are other overt departures from that artist’s style. In Li’s work the table of Cézanne’s original has become a bright red, its flatness echoed by that of the near-monochrome right hand figure, which is presented as an ‘empty’ white silhouette. Despite this emphasis on two-dimensional design qualities to a degree not seen in Cézanne’s own work, Li’s painting also differs from it in having a deeper space. Whereas Cézanne closes off the space behind the figures with a wall, Li opens it up with a landscape. Paradoxically, however, this is exactly the place in the painting where we are most consciously aware of Cézanne, since it is a representation of the immediately recognizable Mont Sainte-Victoire, a feature of the Provençal landscape now indelibly associated with him. Whilst not echoing exactly Cézanne’s own paintings of that mountain, the broken brushwork LI uses to depict it does evoke the earlier artist’s to some degree.

Moving on from this 1980s moment of the rediscovery of Western modernism via reproduction to consider examples closer to our own time I want to look first at Zhang Hongtu (b. 1943). Zhang had emigrated to the United States in 1982, settling in New York, and thus unlike Chinese artists still in their homeland he was able to encounter Western artworks directly. Towards the end of the 1990s (and thus well beyond both his student years and his initial first-hand encounter with Western modernist art) Zhang began a series of works sometimes referred to as his Repaint Chinese Shan Shui Painting project. Each of these works is a version of a well-known Chinese landscape ink painting, repainted in the style of early modernist artists from Europe – specifically Claude Monet, Vincent Van Gogh, and Paul Cézanne. [Plate 18] Ideally to be viewed by a spectator familiar with both originals, perhaps, these works mostly gain their interest from the obvious distinction between the recognizably Chinese subject and composition and a quite different brushwork and colour scheme which echoes the manner of these specific European artists of a much later era. Given that we know the originals to be basically monochrome, the bright colours employed come particularly to our attention. Clearly the shift of medium from ink to oil paint (and absorbent surface to primed canvas) is a precondition for this transformation.

Plate 18: David Clarke, Zhang Hongtu in his Brooklyn studio with works from his Repaint Chinese Shan Shui Painting project, New York, 16 February 2002.

Not all is a matter of clash, however, since the Chinese artists of earlier eras selected by Zhang were themselves as unconcerned with illusionistic realism as the modern Western painters he puts them in dialogue with. Indeed art historical discourse had already at earlier moments compared certain of the Chinese artists Zhang involves in his cross-cultural project with European Post-Impressionists. This is the case with Dong Qichang (1555-1636), for instance, who is the ‘partner’ chosen by Zhang for dialogue with Cézanne on a number of occasions – five works from 1999 and one from 1999-2000 which pair these two artists are illustrated in a book documenting the then-ongoing project published in 2000. [30] That pairing continued in later works: Dong Qichang – Cézanne #9 of 2003, for instance, was exhibited at the Queens Museum, New York, in 2015. [31]

Zhang wasn’t simply choosing his most loved European artists for this project. He uses Monet several times simply because he felt he was the most appropriate partner in terms of style for pairing with certain Chinese artists. He had admired Monet’s paintings a lot at a younger age, but (as he told me in a 2002 interview in New York) he had since come to appreciate Van Gogh and Cézanne (the other two European artists featured in this project) much more. [32] The choice of Chinese artists is much wider than the Western ones, ranging from Fan Kuan (c. 960 - c. 1030) to Shitao (1642-1707). Zhang’s chosen Chinese artists may come from a variety of eras, but he considers it important that they be from earlier time periods than the European ones paired with them – disparity of date is crucial, he feels, creating a ‘time tunnel’ effect in the final work. [33] Choosing European artists from an era when landscape painting had a particular centrality was also a consideration, since all the Chinese paintings are landscapes (or shanshui, literally ‘mountain and water’, the equivalent category - and a highly valorized one over many centuries in the imperial era).

For the most part Zhang is not making reference to specific paintings by the three European artists he involves in his dialogue, unlike the Chinese painters who are always present via particular instances of their art. In Shitao – Van Gogh (1998) and Shen Zhou – Van Gogh # 3 (1999-2000) we might inevitably link the nighttime skies depicted to Van Gogh’s The Starry Night (1889), a painting Zhang would be particularly familiar with since it is a major highlight of the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in his home city, but this is more an exception than a rule. In the case of his paintings which invoke Cézanne as a partner, no such direct references are to be found, and although the rocky mountains and pine trees found in such works will remind us of his paintings these are motifs present in the original Chinese artworks too. One might perhaps think of Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire landscapes when observing the prominent rocky mountain in the background of Dong Qichang – Cézanne # 2, but its profile is not actually similar to that of Mont Sainte-Victoire in any close way, and when Cézanne represents that mountain he doesn’t obscure its lower slopes with cloud as Zhang does in this case (echoing the ubiquity of that motif in Chinese ink painting). The elongated verticality of this particular painting is also very un-Cézanne-like, being an allusion to the Chinese hanging scroll format. Despite the lack of close resemblance to specific paintings by Cézanne, Zhang had indeed closely studied individual artworks by that artist in preparation for this series. In addition to often having references to Western art on his left side (and Chinese references on his right side) while working on these canvases, he also took photographs of original artworks in order to be able to study their brushwork closely.

Speaking particularly of the pairing of Cézanne with Dong Qichang, Zhang notes that there are similarities in their approaches. He sees Dong as already very Cézanne-like in his relatively geometric treatment of mountains and trees, and willingness to eschew closeness to nature. In pairing Cézanne with Song dynasty painter Fan Kuan (as he does in Fan Kuan – Cézanne of 1998, one of the earliest works in this series) he is exploring what he sees as an a ‘monumental’ quality in Cézanne’s representation of mountains that matches that of the source image (Travellers among Mountains and Streams, a work in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei), which is amongst the most famous masterpieces of Chinese painting. In addition to Dong Qichang and Fan Kuan, Zhang also goes on in due course to pair Cézanne with Wang Jian in Wang Jian – Cézanne of 2000, Wang Yuanqi in Wang Yuanqi – Cézanne # 5 of 2007, and with Zhu Da (who is also known as Bada Shanren) in Bada (Six Panels) - Cézanne of 2006. Pairings are not entirely exclusive, however, since the same painting by Fan Kuan that Zhang pairs with Cézanne was also previously paired with Van Gogh in Fan Kuan – Van Gogh of 1998, the first work in the entire series. [34]

Balancing similarity and difference between the two artists is important to Zhang. He puts together artists that he feels have an affinity rather than deliberately confronting radically dissimilar painters, but is aware that there can still be a sense of clash in the resulting work. Nevertheless, he is seeking with this series something more than a collaging of two things that still retain their separate identities – there should be a sense of the final work being one piece, not an assemblage of two parts. He hopes that it would be more like a ‘marriage’ between the two artists, that it would not be possible to separate them. Although the resultant works are entirely distinctive, Zhang has attempted to ‘hide’ himself in the paintings of this series, and not to express his own preferences as to colour or brushwork, his own individual artistic personality.

More recent still than Zhang’s engagement with Cézanne is that of Zeng Fanzhi (b. 1964). His interest in that artist was made clear when he included several of Cézanne’s works in an exhibition he curated in Gagosian’s Hong Kong gallery from 26 March to 11 May 2019, titled ‘Cézanne Morandi Sanyu’. ‘While there are many artists that I like [states Zeng in a press release for the exhibition], Cézanne, Morandi and Sanyu have consistently stimulated my love for painting and also helped me to resolve many problems in my own work’. [35] It is clear that Cézanne (represented in the exhibition by such works as his Fleurs dans un pot d’olives of 1880-82) is the most significant of the three artists to him, while the other two are seen as building on that artist’s breakthroughs. [36] ‘Colour, form and subject are tightly intertwined in Cézanne’s work, and this is what separates his perspective from that of his predecessors’, he states in the same press release. Elsewhere he is quoted as responding to a question concerning which artist is his main point of reference by saying that it is Cézanne: ‘Cézanne is the portal, the central point for everything. Whenever I look at other artists I always think of the relationship between that artist and Cézanne’. [37]

Plate 19: David Clarke, Zeng Fanzhi at the opening of his exhibition ‘Zeng Fanzhi: In the Studio’, Hauser & Wirth, Hong Kong, 8 October 2018.

In an interview about this exhibition project Zeng gives further information about his views on Cézanne: ‘In his work, I think that colour is primarily revealed through contrast, while form is revealed through colour. I imagine that every stroke was painted painstakingly slowly, requiring complete consideration of the transitional relationship between the stroke and the canvas. Every single detail is considered and backed up by a precise and logical thought process. In my opinion, the subject of Cézanne’s painting is unimportant, because no matter what he happens to be depicting, his process bestows a unique beauty on its subject. I think that Cézanne’s process is painting in its purest form’. [38]

In a review of the exhibition Zeng is quoted as describing Cézanne as his ‘longtime companion’ - he had known his work since student days. Zeng also emphasizes that his approach to Cézanne is that of an artist rather than an art historian: ‘it’s purely about looking, for me. I study how he lays every single brushstroke on the surface, how he uses colour to create form and contour’. [39]

Given that engaging with curatorship is something of a detour from his main activity as an artist, it is not surprising to discover that Zeng has also responded to Cézanne in his own artworks. Whereas Zhang tries as it were to act as the neutral intermediary between Cézanne and the Chinese artists he links him to in his paintings, Zeng chooses to respond directly to the French artist in his own artworks. His works engaging with Cézanne were seen in the show ‘Zeng Fanzhi: In the Studio’, held at Hauser & Wirth, Hong Kong from 8 October till 10 November 2018 (at a time when Zeng was maintaining a home in the city). [Plate 19] Untitled of 2018 is one of them. [Plate 20] In this oil painting, deliberately given an unfinished look by the irregular empty white areas in each of its four corners, Zeng takes on the Cézanne-like subject of a small group of pine trees, presented against a blue background. There is no sense of ‘East meeting West’ in this work, no sense of an encounter with exotic otherness.

Plate 20: Zeng Fanzhi, Untitled, 2018, © 2025 Zeng Fanzhi

Cézanne is not the only artist Zeng has responded to, but one feels this is the artist closest to his heart. In 2017 he exhibited work alongside those of Van Gogh in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam in Zeng Fanzhi ǀ Van Gogh, but he admits that this artistic dialogue sprang from the exhibition opportunity itself. ‘If it had not been for the presentation (he states in a dialogue with Gladys Chung featured in the exhibition’s catalogue), I would not have thought of making these new works. My previous perception of Van Gogh was limited to a generic idea of “a great artist”. However, in the process of creating them, I gradually gained a deeper understanding of him’. [40] Wheatfield with Crows of 2017, his take on one of the Dutch painter’s most famous paintings, was one of the images to result. With that work one senses less of a direct engagement with the style of the original than in the case of the distinctly Cézanne-like Untitled of 2018 (which is not a version after a well-known original by that artist) – we are clearly looking at a response by an artist of more recent era. [41] Perhaps Van Gogh is more immediately present in those works in which Zeng responds to that artist’s self-portraits, but only because they (obviously) contain his likeness. A similar lack of engagement with the specifics of another artist’s style is present in Zeng’s From 1830 till now No. 1 of 2014, a version of Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1830). This work was displayed next to that of Delacroix in the Louvre in 2014, and again one feels it is the opportunity which led to the dialogue rather than the other way around. Zeng reworks the earlier painter in his own idiom, wholly taking possession of his image as it were.

In looking at Zhang Hongtu and Zeng Fanzhi’s engagement with Cézanne I hope to have shown that he is still alive as an influence on artists far removed from the time and place in which he lived. Such a sense of the artist as a living presence in relation to art of the contemporary era is not of course the motivation behind bringing ‘Cézanne and Renoir: Looking at the World’ to Hong Kong. This exhibition’s presence in the city is part of a broader recent pattern of bringing art from Western museum collections to Hong Kong. Amongst other exhibitions which have been part of this trend are several which have taken place at the Hong Kong Palace Museum: ‘The Forbidden City and the Palace of Versailles: China-France Cultural Encounters in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries’ (18 December 2024 – 4 May 2025); ‘The Adorned Body: French Fashion and Jewellery 1770–1910 from the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris’ (26 June – 14 October 2024; ‘Botticelli to Van Gogh: Masterpieces from The National Gallery, London’ (22 November 2023 – 11 April 2024); and ‘Odysseys of Art: Masterpieces Collected by the Princes of Liechtenstein’ (9 November 2022 – 20 February 2023). M+, the other art museum operated by the West Kowloon Cultural District (rebranded in 2024 as ‘West K’), has also participated in this trend. Its major show of black and white photography was primarily made up of works from the collection of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. It even used French in its title: ‘Noir & Blanc – A Story of Photography’ (16 March – 1 July 2024).

Whilst the incentive for these shows is of course a desire of their originating institutions (and countries) to promote themselves (and generate revenue from doing so), from the Hong Kong point of view the motivation stems partly from national political considerations. In the 14th national five-year plan of the People’s Republic of China (promulgated in March 2021) Hong Kong was explicitly assigned a role of building cultural links between China and the rest of the world. Chapter 61 of that document states: ‘We will support Hong Kong in developing itself into a center of arts and culture exchanges between China and the world.’ [42] Although the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region government would have had no choice but to take up this task assigned to it by the national leadership, it did so enthusiastically, and chose to interpret the idea of making cultural links between ‘China and the world’ as positioning Hong Kong as a place where East meets West. At the 17 November 2021 opening ceremony of the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology’s Shaw Auditorium, Carrie Lam (at that time the Hong Kong Chief Executive) spoke of that and other recent or then-forthcoming cultural infrastructure developments as helping to position the city as an ‘East-meets-West centre for international cultural exchange’. [43]

The West Kowloon Cultural District Authority seems to have particularly taken on board this ‘East meets West’ rhetoric, as the list of its exhibitions given above indicates. In remarks made on 18 November 2024, the WKCDA chair (Henry Tang Ying-yen) said that it ‘will play the leading role in Hong Kong’s mission to establish itself as the East-meets-West center for international cultural exchange’. [44] Earlier in the same year the WKCDA had already announced that it planned to sign as many as 22 deals with overseas institutions to promote the city’s status as an ‘East-meets-West cultural hub’. [45] Of course the government-run art museums such as the Hong Kong Museum of Art would naturally also have to adopt similar policies to the WKCDA. One of the Hong Kong Museum of Art’s curators who was quoted in the press concerning ‘Cézanne and Renoir: Looking at the World’ used very similar terms to Carrie Lam and Henry Tang, stating that by means of exhibitions like that one ‘where we showcase national treasures from French museums here in Hong Kong, we can show the city as an East-meets-West centre for international cultural exchange’. [46]

Clearly the idea of promoting Hong Kong as site where ‘East meets West’ is slightly different from the idea expressed by the 14th national five-year plan that Hong Kong should develop as ‘a center of arts and culture exchanges between China and the world’. In one sense it is larger, in that ‘the East’ clearly includes much more than China (although there hasn’t actually been a plethora of recent museum exhibitions in Hong Kong featuring art from the rest of Asia), while in another sense it is smaller, in that ‘the West’ is hardly the same as ‘the world’. In a historical moment where relations between China and the United States (and sometimes other countries in ‘the West’) have often been somewhat strained, and China has been explicitly seeking to build stronger ties with countries in other regions - including Africa, the Arab world and South America - that narrower interpretation of the nationally-mandated mission seems difficult to understand. Nowadays the two geographical blocks denoted by the terms ‘East’ and ‘West’ arguably meet in a multiplicity of places around the globe, and of course there are also other long-established sites of their encounter such as Istanbul, a city often thought as having both European and Asian sides.

There is also a further significant reason why the notion of Hong Kong as the place where ‘East meets West’ is potentially a problematic one and that is because it was a description of Hong Kong that was common back in the city’s colonial era. Therefore using that phrase does not represent new thinking of any kind, and might even import unwelcome associations with a bygone time. Overemphasis on the role of Hong Kong as a meeting place for Chinese and world culture might potentially also occlude the promotion in the city itself (and overseas too) of Hong Kong’s own local artistic culture. That of course is a task which will only get done if Hong Kong itself performs it. Since the Basic Law (which governs the city’s life as a Special Administrative Region of China) specifically gives it the right to separate cultural and sporting representation (it has its own pavilion in the Venice Biennale, for instance, and its own Olympic team) it is fully entitled to promote its own art. At the end of 2024, however, neither the governmental Hong Kong Museum of Art nor the WKCDA’s M+ had any kind of comprehensive display of Hong Kong art’s history, whether as a ‘permanent collection’ display or something else. There was nowhere a resident of Hong Kong or a visitor from elsewhere could go to learn about the city’s own art in an in-depth way. That is particularly a failing in respect of M+, perhaps, since that institution was initially conceived as one which would ‘perceive and interpret things from a “Hong Kong perspective”’. [47] The report which came up with the concept for M+ also explicitly stated that Hong Kong ‘is more than a place where East meets West’ when discussing ‘the unique cultural position of Hong Kong’. [48]

Although Hong Kong art of an earlier generation did also sometimes embody a binary East/West logic, and even consciously foreground both Western and Chinese references within the same artwork (as Zhang Hongtu does), more recent art produced in the city has frequently eschewed such concerns, and taken a strategically local perspective. [49] That earlier ‘East/West’ Hong Kong art did find a place in art museum displays during the colonial era, being capable of being presented as politically unchallenging (and even consonant with the official governmental rhetoric), but art with a more local flavour was less likely to get exposure in museums. Even today such art is only partially visible in museum exhibitions, even if it has found widespread opportunities to meet a public in other contexts - in part because of the diversification of the city’s art scene following the mid-1990s establishment of the Hong Kong Arts Development Council, and the funding that body was able to provide for the promotion of local art. [50]

Notes:

1: https://www.musee-orangerie.fr/en/whats-on/exhibitions/paul-cezanne-and-auguste-renoir-looking-world (accessed 9 December 2024).

2: https://hk.art.museum/en/web/ma/exhibitions-and-events/cezanne-and-renoir-looking-at-the-world.html (accessed 9 December 2024). Despite the emphasis on Impressionism in the description, the works by Renoir reproduced on the Museum’s website (and described as ‘highlighted artworks’ from the exhibition) are actually from a later period in his career, well after his Impressionist breakthrough era. The claim that Cézanne (like Renoir) ‘sought to depict the modern world’ is repeated in the handout distributed in the exhibition itself, which also claims that ‘this exhibition […] explores their ways in which they looked at the modern world’. The claim that Cézanne’s primary identity is as an Impressionist rather than as a Post-Impressionist was repeated by a text in a short video introducing the exhibition that was played at its opening on 16 January 2025.

3: Cézanne, from a letter to Pissarro, 2 July 1876, in Charles Harrison and Paul Wood with Jason Gaiger (eds.), Art in Theory: 1815-1900, Oxford, Blackwell Publishers, 1998, p. 550.

4: I discuss Gauguin’s work in Brittany (and subsequently in Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands) in David Clarke, ‘Gauguin, Linguistic Opacity, and Cultural Difference’, Source: Notes in the History of Art, Vol. 38, No. 2, Winter 2019, p. 97-106. Audio files of many of my art history lectures are available (free of charge) on YouTube, beginning with a short introduction to this playlist of lectures. Discussion of Cézanne begins with lecture 11 and continues till lecture 13. Van Gogh and Gauguin are also the subject of lectures earlier in the sequence, and Picasso is amongst the artists discussed later on.

5: Picasso, ‘Statement’ (1943), in Judith Wechsler (ed.), Cézanne in Perspective, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1975, p. 78.

6: Matisse, from a letter to Raymond Escholier, Director of the Petit Palais, 10 November 1936, in Judith Wechsler (ed.), Cézanne in Perspective, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1975, p. 71.

7: Jörg Spiller (ed.), Paul Klee: Notebooks. Volume 1, The Thinking Eye, London, Lund Humphries, 1961, p. 22. Wassily Kandinsky also praises Cézanne as a pioneer in his Concerning the Spiritual in Art (New York, Dover Publications, 1977, p. 17-18).

8: On Cézanne and Poussin see Richard Kendall (ed.), Cézanne & Poussin, Sheffield, Sheffield Academic Press, 1993.

9: Monet’s Impressionist works are often of Paris or its suburbs, but from the end of the 1870s onwards he was often painting away from the metropolis, and even presenting images of unspoiled nature. These later works are best characterized as moving beyond Impressionist concerns, and are often strikingly modernistic. I discuss Monet’s art (including his later work) in David Clarke, Water and Art, London. Reaktion Books, 2010, p. 76-111. Cézanne is discussed in the same book at p. 105-106.

10: Richard Verdi, Cézanne, London, Thames & Hudson, 1992, p. 58. Mary Cassatt also appreciated Pissarro’s teaching skills, claiming at one point that he could even have taught stones to draw.

11: Pissarro, letter to Guillemet, September 1872, cited in Richard Verdi, Cézanne, London, Thames & Hudson, 1992, p. 58.

12: Pissarro, letter to his son Lucien, 22 November 1895, in Judith Wechsler (ed.), Cézanne in Perspective, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1975, p. 34-35. The important one-person exhibition at Vollard’s Paris gallery of November 1895 - the artist’s first - featured 150 of Cézanne’s works.

13: Cézanne, 1905 letter to Bernard, in Linda Nochlin (ed.), Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, 1874-1904: Sources and Documents, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1966, p. 95.

14: The Dreyfus affair began in 1894, the year Alfred Dreyfus was wrongly convicted of treason, and only came to an end in 1906 with his eventual exoneration. Zola, Cézanne’s close friend from the time of their youth onwards, was the prime mover in publicly calling for an overturn of Dreyfus’s wrongful conviction. In the artistic circle Monet was also a supporter of Dreyfus.

15: Cézanne, letter to Zola, 20 May 1881, Alex Danchev (ed.), The Letters of Paul Cézanne, London, Thames & Hudson, 2013, p. 217. Cézanne mentions that he has lent Pissarro ‘Huysman’s book’ - apparently En ménage (Married Life), published earlier that year - which Pissarro was ‘gobbling up’. A letter to Chocquet of 16 May 1881 says he saw Pissarro the previous day (p. 215). In a letter to his son Paul of 20 July 1906 he asks him to say hello to Pissarro’s widow on his behalf (p. 359-360).

16: Both the Pissarro painting and Cézanne’s copy of it are reproduced in the catalogue of Pioneering Modern Painting: Cézanne and Pissarro, and Joachim Pissarro offers a discussion of the similarities and differences between them (Paris, Musée d'Orsay, Cézanne et Pissarro: 1865-1885, 2006, p. 102-107).

17: The two paintings are reproduced side by side in Cézanne et Pissarro: 1865-1885, p. 150-151.

18: Wall text under a heading ‘Viewing in Parallel’ in the Hong Kong showing of ‘Cézanne and Renoir: Looking at the world’. The wall text for Still Life with Soup Tureen describes Pissarro as a ‘fellow Impressionist artist’ to Cézanne, thereby reinforcing the exhibition’s characterization of Cézanne as an Impressionist rather than as a Post-Impressionist.

19: Amongst other treatments of the potato harvest theme by Pissarro is The Harvest, Pontoise of 1881.

20: Meyer Schapiro, Paul Cézanne, New York, Harry N. Abrams, 1952. See especially p. 20 onwards.

21: Formalist interpretations of modern art’s development were at one time quite dominant. The writings of Clement Greenberg were particularly influential in promoting such an approach (see for instance his ‘Modernist Painting’ essay - first published in Art and Literature, No. 4, Spring 1965, p. 193-201, but frequently reprinted since), although it can also be found in earlier writers such as Clive Bell, and later ones such as Michael Fried. I critique formalist interpretations of modern art in David Clarke, ‘The Gaze and the Glance: Competing Understandings of Visuality in the Theory and Practice of Late Modernist Art’, Art History, Vol. 15, No. 1, March 1992, p. 80-98.

22: In a conference taking place alongside the 1995 Hong Kong Museum of Art exhibition ‘Twentieth Century Chinese Painting: Tradition and Innovation’ a speaker who was a senior curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York described artistic modernism as a uniquely Western phenomenon. Even somewhat later, in 2002, another MOMA curator giving a talk in Hong Kong was to present a rather similar story of modern art, albeit that the contemporary Chinese artist Xu Bing was included towards the end of the narrative – by that time it was possible to acknowledge non-Western contemporary art even if the galleries in Western art museums were not rearranging their displays to accommodate non-Western art of the modern era. That process has only begun more recently (and still somewhat tentatively) in major Western modern art museums such as MoMA and Tate Modern. In a similar way, textbooks of modern art (or of art history in general) have tended to prioritize European and American art, simply ignoring or marginalizing non-Western art until recently. The ninth edition of the popular American textbook Art Through the Ages, for instance, contains only one paragraph about twentieth century Chinese art (following on from a previous paragraph which moves from discussion of eighteenth century art to a brief mention of nineteenth century art). This 1991 text comes under a sub-heading in the one chapter on Chinese art which reads ‘Ming, Ch’ing and Later Dynasties’ – there were of course no dynasties later than the Qing at all, as anyone with even the slightest acquaintance with Chinese history would know. This error has been corrected by the tenth edition of 1996, which simply removes mention of the ‘later dynasties’ altogether from the sub-heading (and changes ‘Ch’ing to the Pinyin equivalent ‘Qing’), while retaining the dismissive treatment of nineteenth and twentieth century Chinese art with the same two paragraphs.

23: I discuss the Hong Kong and Taiwan art of this era, as well as the Mainland Chinese art, in David Clarke, China - Art - Modernity, Hong Kong, Hong Kong University Press, 2019 (especially in chapters 4, 5 and 6). Engagement with Western art by Chinese artists of the first half of the twentieth century is covered in chapter two.

24: A self-conscious engagement with specific Western artists (or even specific artworks) was not uncommon in that era, even continuing to be seen in 1990s Chinese art. Examples include Huang Yong Ping’s 100 Arms of Guan-yin (temporarily installed in the Marienplatz traffic island in Münster, Germany in 1997), which references Marcel Duchamp’s Bottle Rack (1914), albeit much transformed in scale and further altered by the addition of mannequin arms holding various objects. Yue Minjun’s The Execution (1995) is an obvious parody of Édouard Manet’s The Execution of Emperor Maximillian (1868-69), itself a painting which alludes to an earlier work by another artist, Francisco Goya’s The Third of May 1808 (1814).

25: The exhibition was ‘”I Don’t Want to Play Cards with Cézanne” and Other Works: Selections from the Chinese “New Wave” and “Avant-garde” art of the eighties’, Pacific Art Museum, Pasadena, California, 1991. A catalogue of the same title and date accompanied the exhibition, edited by Richard E. Strassberg, and Li’s painting is reproduced in colour in it.

26: Richard E. Strassberg, writing in an essay ‘”I Don’t Want to Play Cards with Cézanne” and Other Works’, in Richard E. Strassberg (ed.), ”I Don’t Want to Play Cards with Cézanne” and Other Works: Selections from the Chinese “New Wave” and “Avant-garde” art of the eighties, Pacific Art Museum, Pasadena, California, 1991, p. 28. The essay is p. 23-55.

27: Several of Cézanne’s card player oil paintings were brought together (along with other associated works) in the exhibition ‘Cézanne’s Card Players’ (Courtauld Gallery, London, 21 October 2010 - 16 January 2011; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 7 February - 8 May 2011).

28: Like Wang Guangyi, Yue Minjun also (in 2002) produced a painting entitled The Death of Marat. Whereas Wang doubles the figure of Marat in his image, Yue removes it altogether, leaving only the bath in which David depicted Marat’s corpse.

29: David Clarke, interview with Wang Guangyi, Hong Kong, 19 January 1993.

30: Zhang Hongtu: An on-going painting project, New York, On-going publications, 2000. Shitao, who Zhang pairs with Van Gogh in three artworks illustrated in that book, has also been previously compared by painter Liu Haisu (1896-1994) with Post-Impressionism - see Aida-yuen Wong, ‘A New Life for Literati Painting in the Early Twentieth Century: Eastern Art and Modernity, a Transcultural Narrative?’, Artibus Asiae, 60, No. 2 (2000), p. 297-326 (especially p. 322).

31: That painting is reproduced on p. 23 of the exhibition’s catalogue, Zhang Hongtu: Expanding Visions of a Shrinking World, Durham and London, Duke University Press, 2015.

32: David Clarke, interview with Zhang Hongtu, New York, 16 February 2002. All other points attributed to Zhang in the following discussion are also from this interview.

33: Zhang expressed the idea that in a sense Chinese art history almost followed an opposite course to that of Western art. Whereas it is only in the modern era that Western art moved away from realism, the trajectory is somewhat reversed in Chinese art – he sees Dong Qichang’s painting as more abstract than that of Shitao, for instance.

34: Works with dates up to 2000 mentioned here are all reproduced in Zhang Hongtu: An on-going painting project, New York, On-going publications, 2000. Works of later date are reproduced in Zhang Hongtu: Expanding Visions of a Shrinking World, Durham and London, Duke University Press, 2015.

35: See: https://gagosian.com/media/exhibitions/2019/cezanne-morandi-and-sanyu/2019_Cezanne_Morandi_and_Sanyu_at_Gagosian_Hong_Kong_English_T0KW6eo.pdf, (accessed 7 January 2025).

36: Certainly Cézanne was one of the important influences on Morandi’s art, and like Chinese artists such as Li Chao he encountered him first via reproductions. Several of his early works (from the second and third decade of the twentieth century) have been show to relate closely to particular Cézanne paintings – see Flavio Fergonzi, ‘On Some of Giorgio Morandi’s Visual Sources’, in Maria Cristina Bandera and Renato Miracco (eds.), Morandi: 1890-1964, Milan, Skira, 2008, p. 46-65.

37: Gareth Harris, ‘Making Art History: Zeng Fanzhi organizes first show of Cézanne, Morandi and Sanyu’, The Art Newspaper, 30 March 2019 (https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2019/03/29/making-art-history-zeng-fanzhi-organises-first-show-on-cezanne-morandi-and-sanyu, accessed 7 January 2025).

38: https://gagosian.com/quarterly/2019/04/09/interview-zeng-fanzhi-cezanne-morandi-sanyu/ (accessed 7 January 2025).

39: Zeng Fanzhi, quoted in Jan Dalley, ‘Cézanne, Morandi and Sanyu – a beautiful exhibition by Zeng Fanzhi’, Financial Times, 30 March 2019 (https://www.ft.com/content/9ab2ae3e-5215-11e9-9c76-bf4a0ce37d49, accessed 7 January 2025).

40: The exhibition took place from 20 October 2017 to 25 February 2018, and was accompanied by a catalogue of the same name. The passage quoted here is from p. 47 of ‘A conversation with the artist’ by Gladys Chung (p. 45-51).