藝評

Wong Chun Hoi

楊陽 (Yang YEUNG)

at 9:43am on 16th May 2016

Captions:

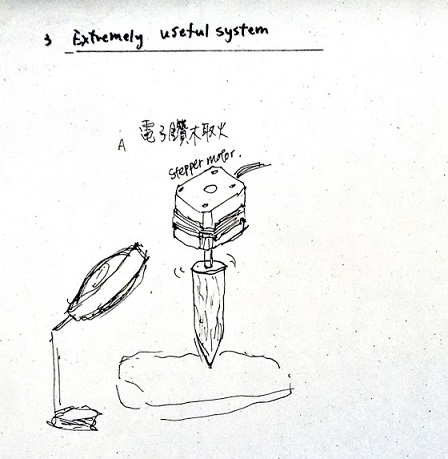

1. & 2. Wong Chun Hoi, extremely useful system #1 - firewood

3. & 4. Wong Chun Hoi, sketches of extremely useful system #1

5. Wong Chun Hoi, hardworking circuit #1.2 (24VDC)

All photos courtesy of the artist Wong Chun Hoi

(原文以英文發表,評論「勤力費電 - 王鎮海不求人」展覽。)

The night of the opening of hardworking burning electricity: wong chun hoi solo exhibition, guests were invited to sit at a rectangular table, one at each end at a time. The table was set in the middle of the multiple and composite iterations made out of hundreds of relay switch. Wong Chun Hoi placed coin-sized pads on the guests’ faces. The pads were linked to a home-use percussive massager. They were then given a finger-size control. Each person could press one button to send the other person an electric pulse, or press another button to intercept the pulse the other person had sent. When both happened to be pressing at the same time, the pulses cancelled out. The participants made their own rules as to who would win in the event, or if there should be a winner at all.

Many pairs took up the challenge. One of them decided to drink beer in the loop. Instantly, they became contestants. As the strength of the electric pulse gradually increased, they fought the involuntary trembling of the beer-holding arm to keep gulping the beer down. Eventually, the person who finished the beer first without spilling won. This particular set of the game might have offered the highest entertainment value, but I found it less intriguing compared to others in which participants were compelled to have a conversation on art by responding to questions Wong put, eg. what they thought art was, how it had brought them into conflicts, whether those conflicts had been resolved, etc. As they returned to their ordinary social selves caught between the questions, transactions of emotional tension became visible but inaccessible to onlookers. The acts of pressing the buttons to send electric pulses might have been intended as defense, but turned out to be also attacks. The scene alluded to the idea of “psychological warfare” that Wong and his collaborators Wong Pui-shan and Teddy Tsui coined to describe the game as it was originally designed when they were still art students five years ago. The heightened sensitivity that directs attention to the consequences of our actions in a social situation is not the goal of the project, but it sets its tone. My question is, How does this game activate the objects around it? How does it frame our experience of them?

Without resorting to the language of war – its violence and impatience, in a series of affective gestures, hardworking burning electricity shows inwardly directed struggles. By this I do not mean the artist’s attempt to show his inner psychology, as if there is a unified self accessible by revelation or representation. I am thinking more of the way Simon O’Sullivan refuses to understand art (and artworks) as objects of knowledge, and chooses, rather, to understand its strength as producing affects. He explains that affects can be described as “extra-discursive and extra-textual.” They are “moments of intensity, a reaction in/on the body at the level of matter. We might even say that affects are immanent to matter. They are certainly immanent to experience.” (1) If hardworking burning electricity could be a case study of the immanence of affect in art, what kind of affect may be at work? I speculate that the composites of the relay switch (according to Wikipedia, an “electrically operated switch, used when it’s necessary to control a circuit by a low-power signal or where several circuits must be controlled by one signal), the basic unit Wong works with in the project, are deliberate responses to several dilemmas Wong happens to find himself in as an artist.

Wong Chun Hoi, detail of hardworking circuit #1.2 (24VDC)

One dilemma has to do with the artist’s relation with contemporary technoculture, in which Wong is thoroughly immersed, while also being aware and critical of the over-abundance of technological products and the over-determining impact of the digital mediation of contemporary life. To respond, hardworking burning electricity shows some one hundred relay switches in a tangle of cables placed as a bundle on the ground, put to work to turn on a disproportionately small LED light on the wall. Hanging from the ceiling are also wooden boards installed with twelve relay switches each. The handmade is excessive relative to its function, but far from the other kind of over-supply of products powered by mass manufacture in the society at large. The handmade shifts our attention on technology from consumption to its process of production and its productive power. In this light, Wong is also taking back the right to open the black box of packaged consumer items and do things to them in his own way.

A possible second dilemma is related to the first. Wong loves the relay switch as the “dumb unit”, while also seeking to resist the temptation to instrumentalize and fetishize it in the context of an exhibition that privileges acts of showing over acts of making. As a response to this dilemma, hardworking burning electricity presents two composite objects without the relay switch. One of them is a scanner with its cover open. Hundreds of unwanted cable cut-outs and occasional dead batteries lay spreading out on the scanner – a show of ruin in its robust potency, impatiently waiting for the scanner to light up and work. The other composite object is a self-turning twig set up on the ground. A magnifying glass pointing at the twig accentuates the eventlessness of the movement, the flattening of the moment in time. As registers of inertia, these objects contrast with the implosion the relay switches create. They become the artist’s self-questioning, his qualms: “Am I not complicit of excess for desiring to critique excess? Am I able to protect the object from exhibitionism?”

The last dilemma has to do with the solo show itself. While the solo show burdens Wong with the usual pressure any emerging artist would be subjected to, in having to show a new body of work as a mark of achievement and commitment, arguably too soon for Wong who has just begun his artistic journey in the last year or so, Wong also needs to reflect on and own his singular journey, which cannot be fully represented by received ideas of an artist’s career and success. To imagine hardworking burning electricity as if it were a response to such topics is to see each composite object in the project as fully connected with each other. They cannot be isolated as individual works in themselves; each one is always already a development, an unwinding, or a reduction of the other. They all become a process that conceptually and symbolically flow to and from each other. For instance, one hundred and twenty relay switches hanging from the ceiling powered a plastic goldfish suspended in midair to tremble. Three hundred and sixty relay switches weigh down on the keyboard of a piano, to power a music box playing a phrase from the movie soundtrack of Hayao Miyazai’s Spirited Away. Hence, the relay switch was put to both use and uselessness in one stroke. Wong says the end points of the circuits don’t matter. I wonder if that’s true, and whether it is exaggerated to discipline himself from making “pretty” things, as Wong told me in an interview. With the ongoing doubt and unfinished reflection on the dichotomy between “pretty” things versus things in themselves in mind, Wong may be compelled to say “it doesn’t matter”, to keep his thinking open.

If the solo in general is the rite of initiation that any artist needs to go through, this hardworking solo is a particular rite of passage for Wong, in the way it resolves him from being motivated by a youthful antagonism directed to the boredom of the world – a yawn or a blink that scorns, to the humility of making one relay switch at a time, pointing it to nowhere but itself as matter immanent with affects, to bring back O’Sullivan.

It is for these dilemmas that I hesitate to call the composite objects ‘works’ of art, for to do so is to set up a theoretical and material distance between each iteration, which I do not think do justice to the project. I had rather see the exhibition itself as the work, which is one material process with an intention of open-endedness. It is also motivated by social concern – confronting what art education does and showing how unlearning is hard work, an ordeal, and cracking the gaps open for those coming into Floating Projects (which Wong co-founded) as a laboratory for artistic and social experiments for the art graduates community. There is no guarantee of success, no didactic social goal of change, but a demonstration of how a new media art education would need to keep asking the question of how technology conceals and hence requires processes of unfolding for its truth to be accessed – for this insight, thanks to Martin Heidegger.

In discussing how ‘affect’ works after the ‘society of ideology’, Brian Massumi says, “The crucial political question for me is whether there are ways of practicing a politics that takes stock of the affective way power operates now, but doesn’t rely on violence and the hardening of divisions along identity lines that it usually brings. I’m not exactly sure what that kind of politics would look like, but it would still be performative. In some basic way it would be an aesthetic politics, because its aim would be to expand the range of affective potential – which is what aesthetic practice has always been about. It’s also the way I talked about ethics earlier. Felix Guattari liked to hyphenate the two – towards and ‘ethico-aesthetic politics.’.” (2) The ethical choice of Wong is to refuse smartism, occasionally distributed in art school for encouraging the use of packaged and downloadable software. He remains open for the other kind to ‘abduct’ him (to borrow Massumi’s term), so he and his art could have a chance of different kinds of excellence, different kinds of success, away from the halo effect.

The one who seeks immediacy with oneself and the world around her, despite or because of the stuttering and hiccups, could be joyfully liberated.

Footnotes:

(1) Simon O’Sullivan, “The Aesthetics of Affect: thinking art beyond representation” in Angelaki: Journal of Theoretical Humanities, volume 6, number 3, December 2001, p.126.

(2) “Navigating Moments – with Brian Massumi” in Hope, new philosophies for change, by Mary Zournazi, London: Lawrence & Wishart, 2002: 235.

Abridged version first published in issue 120 (May 2016) of a.m.post, Hong Kong.